“There Was Blood,” my review-essay of two recent books about the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, appears in the New Yorker on 19 January 2009. What follows is a bibliography and supplementary online smorgasbord, which won’t make much sense until after you’ve read the article itself.

“There Was Blood,” my review-essay of two recent books about the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, appears in the New Yorker on 19 January 2009. What follows is a bibliography and supplementary online smorgasbord, which won’t make much sense until after you’ve read the article itself.

My first debt, as ever, is to the books under review, Thomas G. Andrews’s Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War and Scott Martelle’s Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West, both excellent. Also in print and useful were Rick J. Clyne’s Coal People: Life in Southern Colorado’s Company Towns, 1890-1930, Ron Chernow’s Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and Elliott J. Gorn’s Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America. Marilynn S. Johnson’s Violence in the West: The Johnson County Range War and Ludlow Massacre: A Brief History with Documents arrived too late for me to consult it when writing the article but we dipped into it while fact-checking. Among older sources, the most useful were Barron B. Beshoar’s Out of the Depths: The Story of John R. Lawson, a Labor Leader (1942), George Korson’s Coal Dust on the Fiddle (1943) for lore and songs, George S. McGovern and Leonard F. Guttridge’s The Great Coalfield War (1972), and Zeese Papanikolas’s Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre (1982).

Which should you read, if you want to know more about Ludlow? Martelle has the best day-by-day account of the conflict. Andrews has the most insight into the geological, economic, and sociological forces, and he gives the context of the preceding decades in more detail than any of the others. I think both deserve the highest marks in terms of their scholarship and their accuracy. Beshoar’s father was a doctor who treated the Ludlow strikers, and the strikers named a camp after him. As a result, Beshoar’s version of events is frankly partisan, and sometimes he veers into the propagandistic. His account is one of the liveliest, though, perhaps because he tapped oral sources not available to later writers (don’t be put off by the subtitle; his book is only nominally restricted to Lawson). As you would expect, McGovern and Guttridge are very good about the politics, which got quite complex, as the federal government was brought in against the state, and as various committees undertook to investigate the mine operators and interfere with one another’s investigations in the process. Papanikolas’s is a very nice piece of writing, though a somewhat melancholy one, and he has a novelist’s eye for detail. When Papanikolas tracks down Tikas’s grave, for example, the manager of the cemetery recalls for him how he adopted a runaway St. Bernard on the day of the massacre. Later, reading testimony contemporary with the massacre, Papanikolas finds mention of a St. Bernard loose in the desolate camp carrying a burning timber in its mouth, and he wonders if he’s found the historical trace of the cemetery manager’s animal. Papanikolas’s book is worth reading as much as an essay on the historical impulse as for its account of Ludlow (like Beshoar’s, his book isn’t limited by its apparent focus on a single individual). Though I name-check King Coal in my article, it isn’t Upton Sinclair’s best novel. If you’re hell-bent on reading Sinclair, which I’m not sure you should be, read Oil! instead (and notice, when you do, that in the book, corporate power and false religiosity are hand-in-glove allies—not opponents, as in the movie—and that they are united to suppress the revolutionary force of labor, which the movie knows not of).

The Ludlow massacre and the Great Coalfield War are well documented online. The best compilation is the Colorado Coal Field War Project, produced by the University of Denver, which has a historical outline, a bibliography, photos, a historical map that links to some of the photos, and information about an archaeological exploration of the site. The Holt Labor Library of San Francisco, meanwhile, also offers a Ludlow bibliography, comprised of print and online sources. The Bessemer Historical Society, custodian of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company’s archives and legacy, has published a brief history of the company and sells several texts about mining and CFI in its store, including a reprint of Camp & Plant, the weekly run by CFI’s Sociological Department.

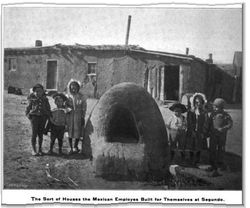

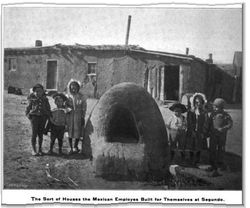

As it happens, Google Books has digitized a stray volume from Camp & Plant, so you can examine for yourself the paternalism of CFI’s early years, as instanced in such photos as these of worker-made adobe homes (left) and the factory-made wood-and-concrete structures that replaced them (right). Here, by the way, is what the factory owners thought of workers who failed to subscribe to their periodical. (Andrews reports that one miner quipped that the mule workforce “was unionized before some of us.”)

As it happens, Google Books has digitized a stray volume from Camp & Plant, so you can examine for yourself the paternalism of CFI’s early years, as instanced in such photos as these of worker-made adobe homes (left) and the factory-made wood-and-concrete structures that replaced them (right). Here, by the way, is what the factory owners thought of workers who failed to subscribe to their periodical. (Andrews reports that one miner quipped that the mule workforce “was unionized before some of us.”)

Most of the surviving photographs of the Ludlow massacre were taken by Louis R. Dold, whom Papanikolas, amazingly enough, tracked down and interviewed for his book. (Elsewhere Dold’s first name is sometimes spelled “Lewis” and his last name “Dodd.”) Dold’s Ludlow photographs, and those taken by several others, are available for browsing in the Denver Public Library’s Western History collection. Here, for example, is an evocative one of the pit below Tent No. 58, which Dold has annotated as follows: “Hole Where Bodies of 11 Women and 2 Children Were Recovered From After Fire at Ludlow Coloney [sic].” You can also see strikers’ children playing in the snow with what is either an effigy or a scarecrow; the chaos in Trinidad when a panicked National Guard general ordered his cavalry to “ride down” a group of women protestors; the Death Special; strikers playing baseball; numerous shots of the Ludlow camp before and after it was razed; and an image of Tikas’s corpse, mislabeled in the Denver Public Library’s files as being that of another striker (the indefatigable Papanikolas writes of having come across the same misidentification when he visited the archives in person).

More cheerfully, there’s also a 1914 photo of a “coal miner’s wife”, whom I believe may be Mary Thomas O’Neal. I’m guessing based on the resemblance between the photos reproduced here. At left is a detail from the Denver Public Library’s photo (call number X-60426). At right is an image of Mary Thomas O’Neal that pops up when you play an oral-history interview with her conducted in 1974 and available online through the Virtual Aural/Oral History Archive at California State University Long Beach. Mary Thomas O’Neal is one of the few Ludlow survivors who left a first-person account, published as Those Damn Foreigners in 1971. As Martelle observes in an end note, her memoir “differs radically” from the testimony she gave shortly after the massacre; Papanikolas had similar doubts about the reliability of her memory when he interviewed her; and the oral history comes with the caveat that she herself was aware that her memory was deteriorating. But there’s no doubt that she was a coal miner’s wife (though she was separated from her husband during the strike); that she was active in the union cause, lending her talent as a singer to its recruiting parties; and that she was in Ludlow camp with her children the day of the massacre. You can hear her, in her eighties, singing the union song “We’re Coming, Colorado,” if you click through to section 1a, segment 11, of the Virtual Aural/Oral History Archive interview with her. (She starts singing roughly at the 1:50 mark.)

More cheerfully, there’s also a 1914 photo of a “coal miner’s wife”, whom I believe may be Mary Thomas O’Neal. I’m guessing based on the resemblance between the photos reproduced here. At left is a detail from the Denver Public Library’s photo (call number X-60426). At right is an image of Mary Thomas O’Neal that pops up when you play an oral-history interview with her conducted in 1974 and available online through the Virtual Aural/Oral History Archive at California State University Long Beach. Mary Thomas O’Neal is one of the few Ludlow survivors who left a first-person account, published as Those Damn Foreigners in 1971. As Martelle observes in an end note, her memoir “differs radically” from the testimony she gave shortly after the massacre; Papanikolas had similar doubts about the reliability of her memory when he interviewed her; and the oral history comes with the caveat that she herself was aware that her memory was deteriorating. But there’s no doubt that she was a coal miner’s wife (though she was separated from her husband during the strike); that she was active in the union cause, lending her talent as a singer to its recruiting parties; and that she was in Ludlow camp with her children the day of the massacre. You can hear her, in her eighties, singing the union song “We’re Coming, Colorado,” if you click through to section 1a, segment 11, of the Virtual Aural/Oral History Archive interview with her. (She starts singing roughly at the 1:50 mark.)