A new article of mine, “Close Encounters,” is published in the 17 January 2022 issue of The New Yorker. It’s about how the science fiction of the Polish writer Stanisław Lem was shaped by his experience as a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust. What follows here is a discussion of some of the sources I drew on for the article—a kind of journalistic “Inside the Episode” featurette—as well as pointers to other Lem resources online. It won’t make much sense until after you read the article—please start there! Or just go there, period. There’s no need to come back here at all, really, unless you like to read footnotes.

As ever, my first debt is to the books under review. Agnieszka Gajewska’s scholarly study of Lem, Holocaust and the Stars, is published by Routledge, in a translation by Katarzyna Gucio. Wojciech Orliński’s Lem: A Life Out of This World hasn’t been translated into English yet, and since I don’t speak Polish, I read it in an easygoing and lively Spanish translation by Bárbara Gill, issued by Ediciones Godot, a publishing house in Argentina. The Godot edition is a beautifully designed little paperback, with lots of photos and illustrations, well worth seeking out if you happen to read Spanish and can figure out a way to order it internationally. The Truth and Other Stories, a collection of Lem’s early tales, many never before Englished, is published by MIT Press, in an excellent translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. In synch with the centenary of Lem’s birth (about which Roisin Kiberd wrote for the New York Times last summer, in an article illustrated with a number of the psychedelic dust jackets that graced Lem’s novels when they came out in Poland), MIT Press has also reprinted in sharp-looking paperbacks Lem’s memoir, Highcastle, and a number of his best novels.

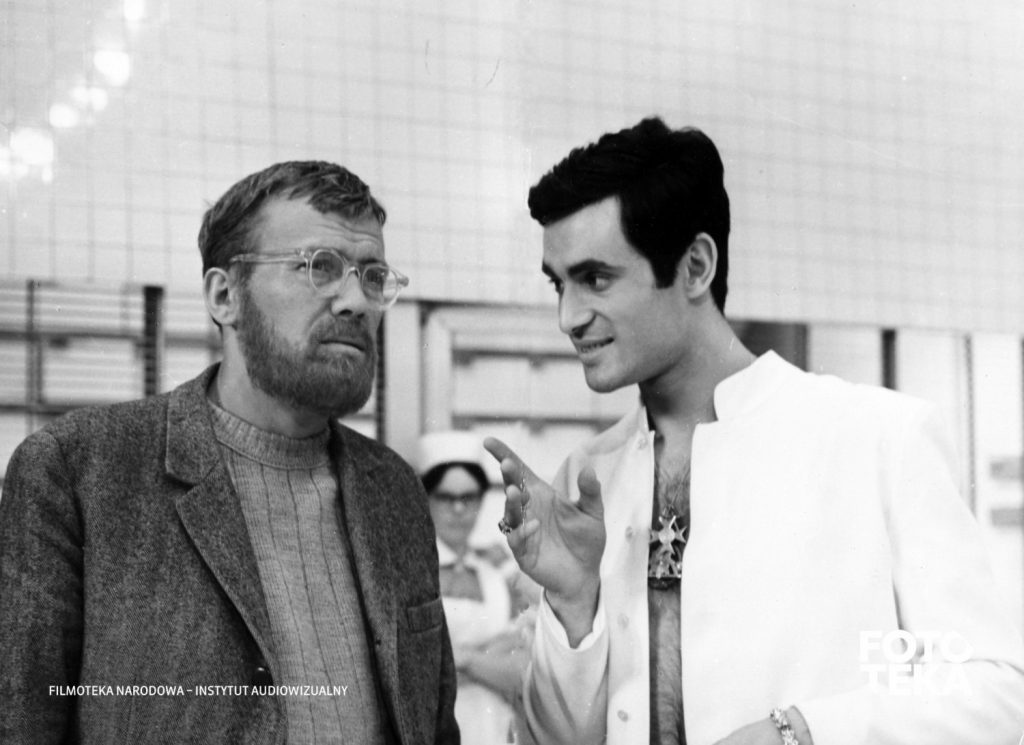

The Criterion Channel streams the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky’s movie of Solaris (1972), along with an interview with Lem about it, excerpted from a Polish television documentary. Steven Soderbergh’s 2002 remake, meanwhile, is streaming pretty much everywhere. Unsophisticatedly, I like both!

While we’re on the topic of differing versions of Solaris, I should maybe explain that when I quote from the novel in my article, I’m using a new translation by Bill Johnston, who’s also responsible for MIT Press’s new translation of The Invincible. Johnston translated Solaris directly from the Polish original, unlike his predecessors Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox, who based their translation on a French intermediary. Kilmartin and Cox’s version is mellifluous, and I very much enjoyed it when I first read the book, but Johnston’s is more faithful to what Lem actually wrote and is also excellent stylistically (though there are a couple of spots where it could have been benefited from a major publishing house’s copy editing team). Unfortunately, though the Lem estate supports Johnston’s translation, his English-language publishers have resisted updating the text of Solaris, and you can only read Johnston’s translation as a Kindle e-book (this is the only time I will be linking to Amazon in this post). You can’t go wrong with either version, honestly, though I ended up preferring Johnston’s, even though I’m a sentimentalist who usually stays attached to the pioneer translation of a classic.

For background about the city of Lviv, formerly Lwów, and about Poland’s history while under the control of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, I consulted Tony Judt’s Postwar, Patrice Dabrowski’s Poland: The First Thousand Years, Norman Davies’s God’s Playground, Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki’s A Concise History of Poland, and Adam Zamoyski’s Poland: A History. For the experience of postwar Poland’s Jewish citizens, in particular, I also drew on David Engel’s article “Poland since 1939,” in the online encyclopedia Yivo, and Dariusz Stola’s article “Jewish Emigration from Communist Poland: The Decline of Polish Jewry in the Aftermath of the Holocaust,” East European Jewish Affairs 47 (2017): 169-88. Marcin Wolk’s review of the Polish editions of Gajewska’s and Orliński’s books, “Stanisław Lem, Holocaust Survivor,” Science Fiction Studies 45 (2018): 332-40, provides details about Lem’s reticence to discuss his Jewish identity.

The one essay in which Lem did reference his Jewish identity explicitly was “Chance and Order,” which appeared in the 30 January 1984 issue of The New Yorker and was reprinted under the title “Reflections on My Life” in the collection Microworlds: Writings on Science Fiction and Fantasy (1984). The Microworlds collection is also where I found Lem casting aspersions on science fiction as a genre. Lem’s letters to his American translator Michael Kandel were published as Stanisław Lem: Selected Letters to Michael Kandel, trans. Peter Swirski (Liverpool University Press, 2014). Swirski is the dean of Lem studies in English, and I owe my knowledge of the contents of several early Lem novels never translated into English, including Man from Mars and Astronauts, to his essay “The Unknown Lem,” which appeared in Lemography: Stanislaw Lem in the Eyes of the World (Liverpool University Press, 2014).

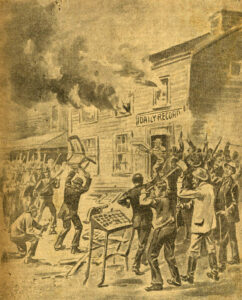

John-Paul Himka’s “The Lviv Pogrom of 1941: The Germans, Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Carnival Crowd,” Canadian Slavonic Papers 53 (2011): 209–43, is the definitive account of what happened during the Lwów pogrom of June 30 to July 2, 1941. (An intriguing byway: the disputes on Wikipedia over the facts of the pogrom are explored by Mykola Makhortykh in “War Memories and Online Encyclopedias,” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 9.2 (2017): 40–68.) Published memoirs by survivors of the pogrom include Janina Hescheles, My Lvov: Holocaust Memoir of a Twelve-Year-Old Girl (Amsterdam Publishers, 2020) and David Kahane, Lvov Ghetto Diary, transl. Jerzy Michalowicz (University of Massachusetts Press, 1990). Janina Hescheles’s memoir mentions a cousin of Lem’s, Henryk Hescheles, who was imprisoned for a time in one of the NKVD’s prisons in Lwów and then died during the Nazi-managed pogrom. Kahane’s memoir describes being given shelter in the private library of the metropolitan of Lwów’s cathedral, an episode that Gajewska hears an echo of in Lem’s Memoirs Found in a Bathtub. I’m not going to link directly here to the Nazi-made film footage of the pogrom that I mention in my article, because the material is difficult and upsetting and I’d rather have you think twice before you view it, but it can be searched for at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website by the accession numbers 1991.260.1 and 2009.356.1 (the museum has two different versions of the film).

The Fredric Jameson quote about Lem’s novel Eden comes from his Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fiction (Verso, 2007). Lem’s novel Among the Dead was never translated into English, and my knowledge of it comes from Gajewska’s and Orliński’s descriptions and quotations, as well as from consulting the Czech translation, which was published, along with the two other volumes in the trilogy, as Nepromarněný čas, transl. Jaroslav Simondes (Mladá fronta, 1959). Fun fact: in an inscription on the front free endpaper of my copy of this Czech version, a factory section of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia writes that the book is being presented to its first owner as a reward for “good work as a propagandist in the Year of Party Training, 1958–59,” which I am told was a kind of adult-ed class for Communists who wanted to go the extra mile.

Gajewska’s and Orliński’s books are my sources for most of the information in my article about Wiktor Kremin’s Lwów recycling company, which is usually referred to in the sources by the German word for a recycling company, Rohstofferfassung. I also found mention of the company in Witold Wojciech Medykowski’s Macht Arbeit Frei: German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939-1943 (Academic Studies Press, 2018). And there is some discussion of the Rohstofferfassung in a biographical chapter in Peter Swirski’s Stanislaw Lem: Philosopher of the Future (Liverpool University Press, 2015). Intriguingly, I noticed, while poking around the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s online collections, that there’s a record that someone named Sever Kahane was, like Lem, employed by Kremin’s Rohstofferfassung during the Nazi occuption of Lviv. I’m guessing that this Sever Kahane is the same person as Seweryn Kahane, who Gajewska reports lived with the Lems for a time during the German occupation of Lwów (he was later killed on 4 July 1946 during a pogrom in Kielce). Maybe the family arranged at the same time for both Kahane and Lem to be employed by Kremin?

Polish literature buffs may be interested in knowing that in Lem’s novel Hospital of the Transfiguration, the mad poet in the asylum is based on the real-life Polish poet Stanisław Witkacy; cf. these articles by Wojciech Sztaba and Jerzy Jarzębski. Witkacy was a personal friend of Mieczysław Choynowski, the professor at Jagiellonian University who hired Lem to write synopses of new scientific literature published abroad.

While working on this article, friends have asked which of Lem’s novels they should start with, so here’s a list of some of my favorites, in roughly descending order: Solaris, Return from the Stars, Eden, His Master’s Voice, Hospital of the Transfiguration (not sci-fi), The Investigation (a detective novel), The Invincible, Fiasco, and The Chain of Chance (a detective novel). And I liked the anthology Truth and Other Stories quite a bit, too, if stories are your way in.

Lem made clear his opinion of Nazis in two reviews of imaginary books. In A Perfect Vacuum: Perfect Reviews of Nonexistent Books (1978), Lem imagines a novel, Gruppenführer Louis XVI by Alfred Zellermann, about a Nazi officer who, after the fall of the Third Reich, absconds to Argentina with a trunk full of cash, trailing an entourage of opportunistic lackeys. In Argentina he decides to force his parasites to act as though he really is the French king Louis XVI, and the result is something like the HBO show Succession if scripted by Brecht. Lem responded to Hannah Arendt’s writings on Nazis in another review of an imaginary book, though this time “with complete seriousness and not ironically,” as he explained to his American translator. The essay/”review” was titled “Provocation,” and I read it in a French translation, Provocation; suivi de Réflexions sur ma vie, trans. Dominique Sila (Éditions du Seuil, 1989).

The streaming site Mubi is showing half a dozen adaptations of Lem’s fiction in honor of his centenary, including an early Andrzej Wajda short, with costumes and sets so swinging that they make the Austin Powers movies look chaste, about a racecar driver whose reconstructive surgery draws on parts from so many different bodies that it isn’t clear whether he’s himself, his brother, or his sister-in-law. I recommend Ikarie XB 1, a Czech adaptation of an early Lem novel, which Kubrick borrowed from rather liberally when designing 2001. Orliński was the writer for a 2015 documentary, Stanisław Lem: Autor Solaris, directed by Borys Lankosz, which has appeared on Arté and Mubi though it doesn’t seem to be streaming anywhere at the moment. There’s an excellent podcast about Lem produced by Poland’s Ministry of National Culture and Heritage, a link on the webpage for which leads to the Belarussian Lem scholar Wiktor Jaźniewicz’s monumental Lem-focused book collection.