I managed to transfer all the entries from my old blog to this one, and they’re now available if you click on the Archives headline in the right column (or on the word in this sentence). My thoughts on the making of mix tapes, my hatred of deckle edges, and my scan of a lithograph of the Durham ox are now saved for posterity (or at least until the next technological shift).

Would you like a gift receipt with that?

The other night, a friend in publishing mentioned in conversation that December sales had been disappointing throughout the industry this past year. The 2006 holidays had brought an upward bump, as people bought books as gifts for family and friends, but the bump was smaller than expected.

His comment intrigued me, because I wondered if it might be another sign of the qualitative change in the culture caused by the decline in literary reading. Buying a book for oneself is a relatively straightforward thing to do; all that’s required is that you like to read, are in the mood to, and have enough money or credit to effect a purchase. But it’s a bit more complicated to buy a book as a gift. The person you’re buying for has to be a reader, and you have to be one, too, because you have to feel confident that you can choose a book worth reading. Moreover, you have to know enough about the recipient’s reading habits to choose one she would probably like but hasn’t read already. In other words, the two of you have to have been having a fairly sophisticated, ongoing conversation about what you read and what you like to read.

Thus the purchase of books as gifts is probably a more fragile statistic than the purchase of them for oneself, and if literary reading is on the decline, one would expect books to be bought less frequently as gifts. One might even expect that the proportion of books bought as gifts would decline more steeply than book-buying generally. And that does seem to be what’s happening, to judge by retail bookstore sales reported to the U.S. Census Bureau.

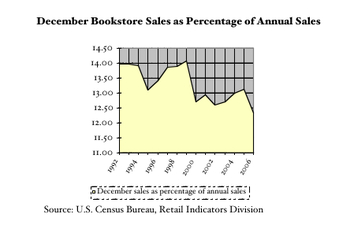

Here’s a graph of annual bookstore sales (in light green) and December bookstore sales (in dark green). Before anyone gets too optimistic, yes, it’s true that aggregate bookstore sales have grown at what looks like a healthy rate. But so has the U.S. population, and so has consumer spending overall during this period, and book sales have not kept pace. In 1985, the average U.S. household spent $141 on reading, out of a total entertainment budget of $1,311 and a total consumer expenditure of $23,490. In 2004, the average household spent $130 on reading, out of a total entertainment budget of $2,348 and a total consumer expenditure of $43,395. (Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2007 Statistical Abstract.) The upward trend you’re seeing here is the result of more people and more money in America, not of an intensification of reading.

If you divide the December sales by the annual sales, you get the yearly percentage of book sales that occur during the holidays. As you can see, if December sales are a reasonable proxy for gift sales, then people have been buying fewer books as gifts, comparatively speaking, over the last decade and a half—another sign, I think, that the place of literary reading in American culture is shifting.

(A side note: Though I didn’t chart them, the largest spikes in book sales every year aren’t in December at all; they’re in August and January, as students buy books for courses. I haven’t checked yet to see whether these are becoming a higher proportion of reading expenditures, but if they are, that would be another dark sign, in my opinion…)

POSTSCRIPT (1 September 2007): I think this post is safely too outdated for anyone to be in danger of referring to it any more, but in case anyone does, there’s a major flaw in my data above. The Census department’s numbers only include brick-and-mortar book sales, not online book sales. Now, since Amazon automatically does packaging and mailing, it’s super convenient for book giving. It’s possible, therefore, that the decline in month-of-December sales noted above is *not* a decline in giving books as gifts, but rather a shift toward buying gift books online.

Where’s Thomas?

In the 2 March 2007 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Patrick McCaughey pans William S. McFeely’s new biography of Thomas Eakins, writing that McFeely’s "view of evidence may satisfy the claims of modern American historiography, although I rather doubt it. It certainly makes for bad art history." In particular, McCaughey is dismissive of the evidence that McFeely presents of Eakins’s homosexuality. Or rather, fails to present, according to McCaughey, who accuses McFeely of making his case by mere assertion. In the 29 March 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books, Christopher Benfey is more polite and circumspect but doesn’t seem any more convinced, calling McFeely’s book "impressionistic and elliptical," noting its "odd combination of historical detail and orphic pronouncements," and offering praise of startling modesty: "Some of his hypotheses seem worth pursuing. . . ."

In the 2 March 2007 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Patrick McCaughey pans William S. McFeely’s new biography of Thomas Eakins, writing that McFeely’s "view of evidence may satisfy the claims of modern American historiography, although I rather doubt it. It certainly makes for bad art history." In particular, McCaughey is dismissive of the evidence that McFeely presents of Eakins’s homosexuality. Or rather, fails to present, according to McCaughey, who accuses McFeely of making his case by mere assertion. In the 29 March 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books, Christopher Benfey is more polite and circumspect but doesn’t seem any more convinced, calling McFeely’s book "impressionistic and elliptical," noting its "odd combination of historical detail and orphic pronouncements," and offering praise of startling modesty: "Some of his hypotheses seem worth pursuing. . . ."

The two reviewers sharply disagree, however, on at least one issue. Both think that Eakins painted himself into The Gross Clinic (above left, 1875, Philadelphia Museum of Art and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), the famous painting of a medical professor with blood on his hands, standing heroically beside a patient with a sliced-open leg, in a surgical theater full of students (a painting recently saved from acquisition by the Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges). But they differ as to where in the painting Eakins’s self-portrait is supposed to be. "Eakins himself crouches in the bottom right-hand corner spattered with blood, holding one of the retractors for the incision," writes McCaughey in the TLS. "Among the students, Eakins has painted a shadowy portrait of himself, dispassionately taking notes," writes Benfey in the NYRB.

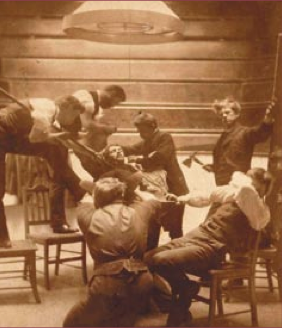

So where’s Thomas? (Since I was too bleary with a head cold to do anything useful this afternoon, I decided to track down the answer in Columbia’s databases.) Eakins and some of his students once posed for a parody (right, c. 1875-79, Woodmere Art Museum) of The Gross Clinic, and in a 1999 article for the journal Representations, art historian Jennifer Doyle wrote of the photograph, "I would like to assert that it is Eakins who poses in the role of the womanly, melodramatic spectator, though I cannot say for certain that it is him." Intriguing as her speculation is, of course, it doesn’t decide the case at hand.

So where’s Thomas? (Since I was too bleary with a head cold to do anything useful this afternoon, I decided to track down the answer in Columbia’s databases.) Eakins and some of his students once posed for a parody (right, c. 1875-79, Woodmere Art Museum) of The Gross Clinic, and in a 1999 article for the journal Representations, art historian Jennifer Doyle wrote of the photograph, "I would like to assert that it is Eakins who poses in the role of the womanly, melodramatic spectator, though I cannot say for certain that it is him." Intriguing as her speculation is, of course, it doesn’t decide the case at hand.

A number of critics have suggested that Eakins is to be seen in the painting as the patient etherized upon the table, or as Dr. Gross, or as both. But this is wandering into interpretation, I’m afraid.

More hardheadedly, in a 1969 article in the Art Bulletin, Gordon Hendricks gave a full list of originals of the painting’s dramatis personae. Hendricks identified the woman in the painting’s left as very likely the patient’s mother, the man in the lower right holding the incision open as Dr. Daniel Appel, the man with the sideburns exploring the wound as Dr. James M. Barton, the holder of the patient’s legs as Dr. Charles S. Briggs, the anesthetist at the patient’s head as Dr. W. Joseph Hearne, and the man writing at the desk to the left of Dr. Gross as Dr. Franklin West. The two shadowy men in the tunnel to the right of Dr. Gross are Hughey the janitor and Dr. S. W. Gross, the central figure’s son. "At right center, looking intently down at the proceedings with pencil and pad, the artist has painted himself," Hendricks concludes. (Hendricks doesn’t identify the patient. He does say, though, that "the operation is for the removal of a sequestrum," a piece of dead bone tissue that forms during chronic inflammation of the bone.)

A description on the website of the painting’s former owner, Thomas Jefferson University, also identifies Eakins as "the first figure seated to the right of the tunnel . . . sketching or writing." In other words, Eakins is the figure about two-thirds of the way up the painting’s right edge, not easy to discern in the reproduction here, or in any reproduction I have at home. It seems as if Benfey is right, and as if the TLS has for once nodded. Whether Eakins was gay, on the other hand, is a controversy I decline to adjudicate this afternoon.

Mass-Observation Online

The University of Sussex’s archive of Mass-Observation, the British movement I wrote about for the New Yorker in the fall, has been digitized by a company called Adam Matthew Digital. The database looks quite fun: all the day-surveys, all the diaries, all the directives, and all the books. And yet, somehow, there is "no overlap with the microfilm series," or so the snazzy pamphlet claims. There are also some Humphrey Spender photographs—rather nice ones, if what’s visible in the pamphlet is representative. The price tag, alas, is $49,500, but I can always hope that Columbia or the NYPL buys a subscription.

Queer or peculiar?

While I was reading up on Andrew Jackson last month, I stumbled across what sounded like a love story between two men, a story I hadn’t heard before. During the Battle of New Orleans, at the end of the War of 1812, the Jewish merchant and philanthropist Judah Touro was hit in the thigh by a cannonball while on militia duty. Touro had enlisted as a common soldier. When news of his injury reached his friend and fellow merchant Rezin D. Shepherd, who was serving as an aide to a naval commodore, Shepherd reacted dramatically: he left his post, found Touro, put him in a cart, carried him to his house, hired nurses to care for him, and thereby saved his life.

Shepherd’s spontaneous actions were risky. Under Andrew Jackson’s command, soldiers were sometimes shot for leaving their posts without permission. Naturally enough, Touro and Shepherd "were ever afterwards inseparable in this world," according to the 19th-century historian Alexander Walker. When Touro died, he left half his fortune to charity and the rest to Shepherd, between $500,000 and $750,000. That sounds like no more than gratitude, except for a further detail: Walker writes that Touro and Shepherd "lived under the same roof" even before Shepherd saved Touro’s life.

The detail would seem to put Shepherd and Touro’s relationship in a different light. Is there more to the story? Over the past month, when I’ve had a spare moment, I’ve tried to find out a little more about Touro and Shepherd. The short answer: Inconclusive.

Touro never married. I don’t know yet whether Shepherd did, but probably so; he had at least one daughter. It turns out that Touro was rather famous as a philanthropist; he gave money not only for the Bunker Hill Monument but also to Mass General Hospital in Boston and Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and to churches and synagogues in New Orleans, New York, Newport, and elsewhere. He even left $50,000 to Sir Moses Montefiore for relief of the poor in Jerusalem. And he was almost as famous as an eccentric. Though one of the richest men in America, Touro "usually ate his meals by himself, and . . . resided in cheap boardinghouses until relatively late in life," according to the American National Biography—a description that seems to contradict Walker’s claim that Touro and Shepherd lived together. But the ANB adds, somewhat cryptically, "What has not been learned since [Touro’s] death continues to puzzle scholars."

In 1955, the scholar Bertram Korn argued in the Jewish Quarterly Review that Touro had been praised as a Jewish philanthropist more than he deserved to be. Korn suggested that Touro was in fact guilty of an inexplicable "indifference towards Jewish life" and felt that the credit for Touro’s bequests should actually go to a journalist named Gershom Kursheedt, without whose charm, patience, and persuasive powers, Korn believed, Touro would have left his money only to civic charities. Korn shed no light on Touro’s special bond with Shepherd, but he did quote a number of Kursheedt’s private expressions of frustration with Touro. "You know he is a strange man," Kursheedt confided to a friend, and likened the millionaire to a snail or a crab. "Mr. Shepherd tells me I must be very careful to humor him or in an instant all may be lost."

In the end, I can’t say whether Touro was queer or merely peculiar. A couple of sources relayed a rumor that Touro remained a lifelong bachelor because in youth he had been in love with a cousin, Catherine Hayes, and had never got over his broken heart when their family separated them. But the sources were careful to specify that it was no more than a rumor. Another source adds that "he certainly avoided the society of ladies and was never willing to exchange a word with them." But that doesn’t really tip the scales either; social awkwardness would explain that behavior better than homosexuality would.