The house bloggers of The New Republic are agitating for a new American book review, which would bring to an intelligent lay readership the news to be found in the thousands of scholarly books published every year. Their model seems to be Britain’s Times Literary Supplement (which, I agree, is well worth the more-than-$150-a-year price tag). "At the moment there is a hole in our cultural life where a bridge needs to be built," writes Jeffrey Herf.

The project sounds worthy, and I hope it happens, though I’m not optimistic. My gloomy suspicion is that the hole in the culture is a geological fault that’s likely to widen, and that any bridges built across it are likely to founder unless they’re made of something highly stretchable. Though many observers (and good friends of mine) do not believe that there’s a reading crisis, I think that something happened to the nation’s reading habits and skills in the past decade or two (click here for a meandering essay of mine on the subject). It seems possible to me that a healthy, high-volume exchange of ideas between the scholarly community and the general public may be a part of the collateral damage.

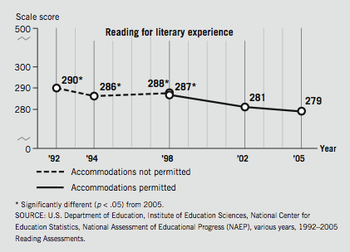

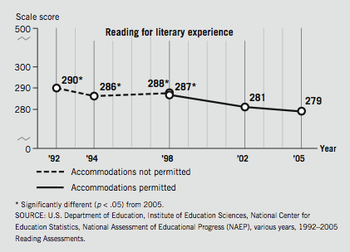

As it happens, last week brought another piece of evidence about the reading crisis, when the National Center for Education Statistics released the results of the 2005 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). As the New York Times reported on 23 February 2007, "It showed that the share of 12th-grade students lacking even basic high school reading skills . . . rose to 27 percent from 20 percent in 1992. The share of students proficient in reading dropped to 35 percent from 40 percent in 1992."

It’s the loss of proficient readers that most concerns me, and that is

most likely to have an impact on what might be called the country’s

intellectual health. If you download the 2005 NAEP

and take a closer look, you’ll see that they assessed three kinds of

literacy: reading for information, reading to perform a task, and

reading for literary experience. No prize for guessing which declined

the most steeply.

In the Chronicle of Higher Education, Lindsay Waters recently noticed the general, nationwide decline of reading, and blamed professors for it. "We have distinguished professors of literature at elite universities promoting methodologies of study that positively discourage reading," Waters wrote. I’m inclined to exonerate the professors. They’ve been trying to make literature seem harder than it is for a long time; it’s only in the last couple of decades that they’ve been able to succeed. The temptation to blame them for it is a perspective mistake, I suggested in a little essay I wrote for n+1 last year. Did the chicken expel the egg, or did the egg abandon the chicken? My guess is that academic literary critics lost their interest in such humane values as style, pleasure, and taste after they lost their audience among the general public, not before. Nothing they did or wrote caused the divide. It only seemed that way if you spent a lot of time reading them (or, er, us).

The loss lamented by the New Republic bloggers—that is, of the public intellectual’s niche in the ecosphere—is probably of a piece with the waning of the pertinence to literature of scholarship in the literary humanities. Thus my pessimism about the prospects of their proposed review. (I reviewed Richard Posner’s book on the demise of public intellectuals for The Nation a few years ago; as it happens, he called in that book for the creation of a periodical not unlike the one the TNR-ites are asking for.) In the unlikely event that the TNR bloggers do succeed, however, I hope they won’t take too seriously all of their pronouncements about what is and is not proper in a book review. Some of those pronouncements seem to me symptomatic of a declining participation in the public sphere, rather than diagnostic of it.

For example, I’m glad that Herf recognizes that a well-written book review does more than merely rate the book in question, and is also supposed to engage with its ideas. But Eric Rauchway (scroll down for his contribution) admonishes would-be reviewers as if their first loyalty should be to the authors of the books they review, and as if they oughtn’t dare write one at all if they haven’t been properly credentialed. "Write a book before you review one," commands Rauchway. As Samuel Johnson once replied, to a very similar stricture, "Why no, Sir; this is not just reasoning. You may abuse a tragedy, though you cannot write one. You may scold a carpenter who has made you a bad table, though you cannot make a table. It is not your trade to make tables."

Rauchway also orders reviewers to "Write about the book you’re reading, not . . ." and then interdicts a number of topics, all of which might well enhance and illuminate a review, which is a species of essay, whether he likes it or not, and as such is perfectly entitled to take a book merely as an occasion and to be as whimsical and digressive as it pleases, unless we’re to be condemned to a narrow utilitarian consumerism. Rauchway further orders reviewers to "Avoid quips," and here, too, I disagree. I’m against gratuitous and excessive malice, but obsequiousness is no more desirable than sadism in a book reviewer, who should not have to worry too much about the vanity of the author. Sometimes a joke is the quickest and liveliest way to make a point. And from time to time there are some real zingers in the TLS.