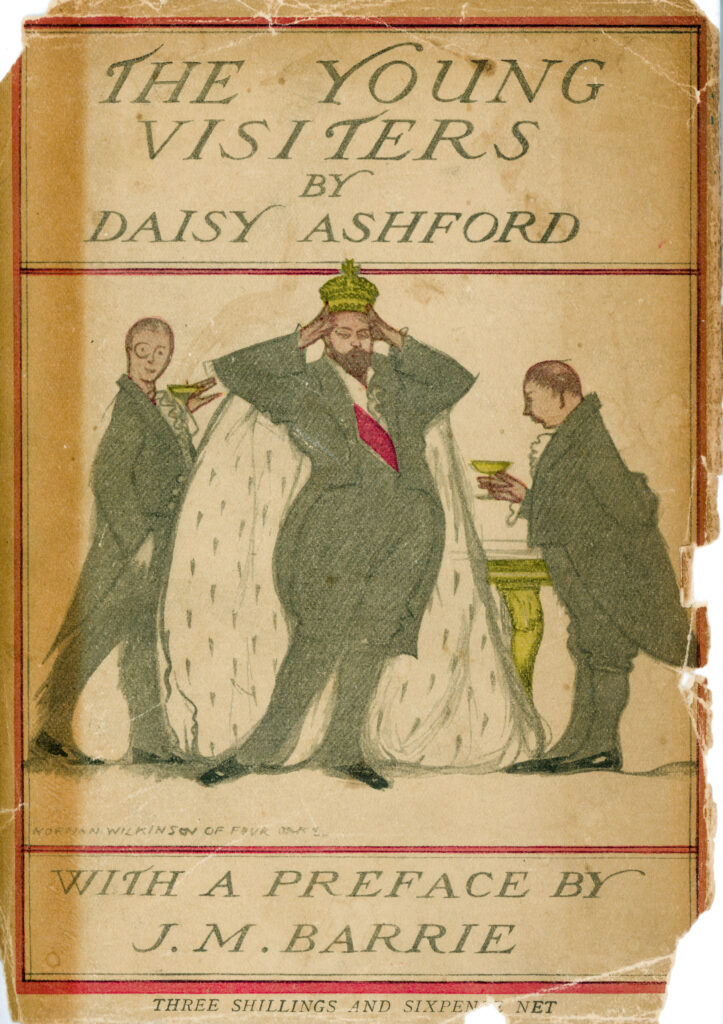

I wrote for Public Books about Daisy Ashford’s The Young Visiters, a best-selling comic novel from 1919, written when its author was nine. The novel is about social climbing, and my essay is about knowing and not knowing.

Category: criticism

Paperback writer

My novel Overthrow had a cameo in the New York Times Book Review’s Paperback Row column this weekend, because it’s coming out in paperback on Tuesday, in a new forest-green-on-mustard colorway.

If you’re reading this, you probably already know, but the novel is about mind-reading, homosexual love, the internet, graduate school, friendship across the color line, the problem of political sovereignty, and the fate of poetry under late capitalism. Please buy a copy from Books Are Magic, McNally Jackson, Greenlight, Word, Powell’s, Book Passage, or Book Soup, if you haven’t already got the hardcover! Viking/Penguin has links to other booksellers on its website, and there are links to the reviews on my blog. The paperback comes with new blurbs from Astra Taylor, director of What Is Democracy? and Examined Life, and Anna Wiener, author of Uncanny Valley, for which I’m very grateful.

In other news, heads up, there’s going to be longish, sci-fi-ish short story by me in a near-term-future issue of n+1, so renew your subscription now. And a regular-length short story of mine, also not quite realist, will appear online at The Atlantic soon.

Please don’t take away from this news the impression that I’m the sort of person who has been able to be productive during the pandemic. All this writing was done in the before-times (in a manic phase that was accompanied by a dread that something terrible was about to happen). Since the lockdown I’ve been mired in a slough, and the only thing I seem able to do is take pictures in Prospect Park. So here, gratuitously, are a couple of deep cuts from last week, not previously released on my blog or on Instagram. An alternate shot of a great blue heron:

And an outtake of a green heron:

The algal bloom maybe very loosely rhymes with the paperback’s color scheme?

Recommendations

- Kate Bolick on writers’ houses (NYRB): “Standing in Millay’s study, surrounded by her books, I knew how comfortable it would be to sit in her armchair reading all day—and felt a pang to realize that, of course, the most recent volume there was published in 1950; our libraries stop when we do.”

- Hermione Hoby on Sylvia Townsend Warner (Harper’s): “The women’s conjugal intimacy is suggested by Sophia sitting up in bed beside Minna and eating a biscuit in order to marshal her thoughts. Minna encourages her to have another. It all feels very English.”

- Amia Srinavasam on gender and pronouns (LRB): “The singular ‘they’ has been in use for more than six hundred years. The OED cites its first recorded use in 1375, in the romance William and the Werewolf: ‘Hastely hiȝed eche … þei neyȝþed so neiȝh.’ ”

- Thomas Meaney on Trumpism after Trump (Harper’s): “What was needed was ‘class warfare’—or perhaps more precisely, a war within the elites—to ensure that the future remained Trumpian and did not revert to the globalist highway to nowhere.”

- Christian Lorentzen on J. M. Coetzee’s Jesus trilogy (Harper’s): “What the reader will remember will be the pleasures available to anyone: the deadpan humor, the swoons of their melodramatic thriller plots, and the beguiling weirdness of the world Coetzee has constructed.”

- Frances Wilson on the bedroom talk of writers in couples (TLS): “Other people’s intimacy is always disturbing, and never more so than when it involves the use of animal names.”

- Charles Petersen on adjunct torture porn (NYRB): “When a Victorian poetry professor calls it quits, so, at many institutions, does her entire subfield. Who wants to know they will be the last person to teach a seminar on Tennyson?”

- Paul Elie on Flannery O’Connor (New Yorker): “All the contextualizing produces a seesaw effect, as it variously cordons off the author from history, deems her a product of racist history, and proposes that she was as oppressed by that history as anybody else was.”

- James Campbell on Ralph Ellison’s letters (TLS): “ ‘I am a writer who writes very slowly,’ Ellison would admit to one correspondent after another as the years rolled by.”

- Abigail Deutsch misses her laundromat (TLS): “Sometimes these women yank my belongings out of my hands; sometimes they’re gentler, and take a cooperative approach.”

- Giles Harvey on Jenny Offill’s Weather (NYRB): “It is an audacious and, as it turns out, slightly misbegotten project, like painting a house with a toothbrush.”

- Patricia Lockwood on having coronavirus (LRB): “‘Jason’s cough is fake,’ I secretly texted a friend from the bathtub, where I couldn’t be monitored. ‘I … don’t think his cough is fake,’ she responded, with the gentle tact of the healthy. ‘Oh it is very, very fake,’ I countered, and then further asserted the claim that he had something called Man Corona.”

A Panel on criticism & social media

On Tuesday, February 18, at 7pm, Naomi Fry, Ben Ratliff, and I will talk about criticism and social media, under the guidance of Eric Banks of the New York Institute of the Humanities, at the McNally-Jackson bookstore’s new South Street Seaport location, at 4 Fulton St., New York. I’ll probably end up referencing this 2015 Harper’s essay of mine about the problem. Please come!

Led astray

Reading this much of a critic’s work will also alert you to his tics. Lane has only one that annoys me: He will cross the street, walk around the block, catch a cross-town bus and wait in line for an hour to make a dopey pun, and unfortunately we are forced to go with him. For the pun-averse this can sometimes feel like engaging in one of those seemingly straightforward conversations that turns out to be the wind-up for an evangelical pitch or an obscene phone call; you wonder if Lane has enticed you through a whole paragraph on “Braveheart” solely so he can hit you with a groaner like “Fast, Pussycat! Kilt! Kilt!”

Samuel Johnson on Shakespeare:

Shakespeare with his excellencies has likewise faults . . . A quibble is to Shakespeare, what luminous vapours are to the traveller; he follows it at all adventures; it is sure to lead him out of his way, and sure to engulf him in the mire. It has some malignant power over his mind, and its fascinations are irresistible. Whatever be the dignity or profundity of his disquisition, whether he be enlarging knowledge or exalting affection, whether he be amusing attention with incidents, or enchaining it in suspense, let but a quibble spring up before him, and he leaves his work unfinished. A quibble is the golden apple for which he will always turn aside from his career, or stoop from his elevation. A quibble, poor and barren as it is, gave him such delight, that he was content to purchase it, by the sacrifice of reason, propriety and truth. A quibble was to him the fatal Cleopatra for which he lost the world, and was content to lose it.