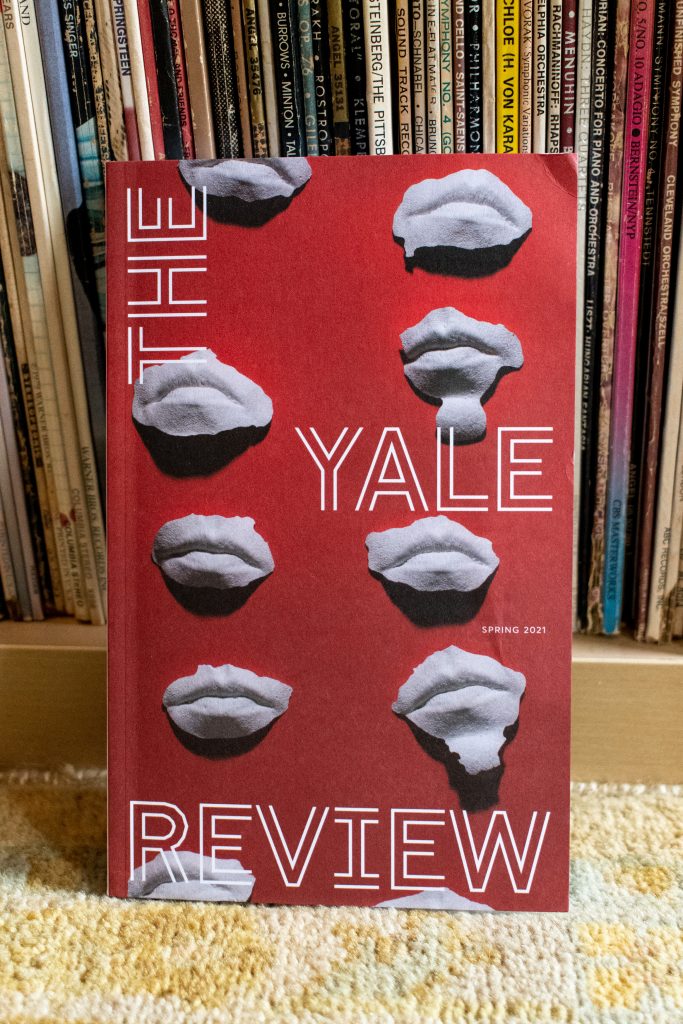

“Massachusetts,” my new short story in the Yale Review, is now available online.

Category: children

A new short story in “The Yale Review”

A new short story of mine, “Massachusetts,” is published in the spring 2021 issue of The Yale Review. The story is about how a group of children are shaped by two teachers whose styles of being are incommensurate. It’s a tiny bit allegorical, but realist enough that you might not notice.

If you’d like to read it, you can get just the spring 2021 issue of The Yale Review for $15, or you can get a year’s subscription (four issues) for $44, along with a coupon for 50% off some of Yale University Press’s books.

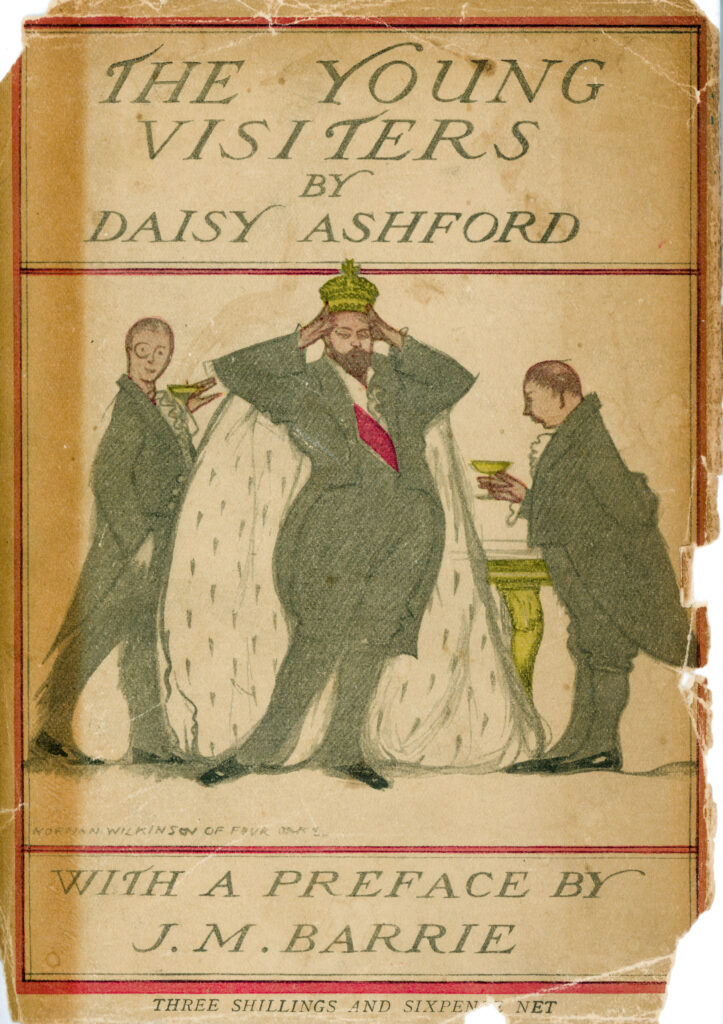

“You will look very silly”

I wrote for Public Books about Daisy Ashford’s The Young Visiters, a best-selling comic novel from 1919, written when its author was nine. The novel is about social climbing, and my essay is about knowing and not knowing.

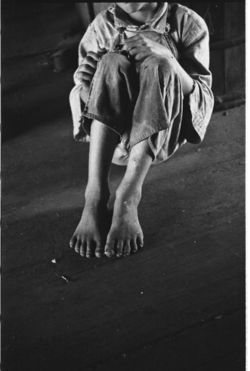

Agee’s ekphrases

Before I started reading for my recent New Yorker article “It Happened One Decade,” I hadn’t actually read James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) all the way through. I vaguely recall that I was supposed to have done so in college, but I didn’t. That’s probably a good thing, according to comments that Evans made in 1974 when his photographs were exhibited at the University of Texas at Austin. Agee “wouldn’t approve of reading Let Us Now Praise Famous Men for a class assignment,” Evans wrote, “because it robs the work of its freedom. Agee was never reasonable about the heavy hand of duty.”

Reading it at age forty-two, however, I kind of loved it, even if (like Morris Dickstein, the author of the book I was reviewing) I couldn’t help but roll my eyes at the portentous table of contents and other elements of gratuitous “structure.” This excess does have its rewards, however, including a sense of depth—a sense of the complexity of reality. Several times over, from different perspectives, Agee describes the home of the family whom he calls the Gudgers (in real life, their last name was Burroughs), and different aspects emerge each time. On page 153 (of the Houghton Mifflin edition), for example, Agee writes that the family’s

left front room is used only dubiously and irregularly, though the sewing machine is there and it is fully furnished both as a bed room and as a parlor. The children use it sometimes, and it is given to guests (as it was to us), but storm, mosquitoes and habit force them back into the other room where the whole family sleeps together.

Agee returns to the room much later in the book, on page 419, when he finally gets around to describing the first night that he spent with the Gudger/Burroughs family. He describes the parents “telling me where I would sleep, in the front room” and then describes the “waking and bringing-in of the children from their sleeping on the bed I was to have.” There’s a touch of inconsistency between these observed facts and the general observation made earlier, and it occurred to me that the Burroughses, wanting to be hospitable, may have told Agee a white lie about how often the children used the room. Surely a family with so few resources would have made regular use of a bedroom that they kept furnished, even if it was drafty. If it were true that the Burroughs children didn’t often sleep in the bedroom because it was too easy for mosquitoes and rain to get in, why were the children sleeping there on the night of Agee’s arrival, which took place in July, during a downpour? Of course it only makes the Burroughs family seem even more appealing to think that they might have fibbed to help Agee feel at home.

Among the book’s many pleasures is comparison of Agee’s prose descriptions of the tenant farmers’ habitats with Evans’s photographs of them. At the start of the section titled “A Country Letter,” for example, Agee describes in detail a coal-oil lamp in the Burroughs’ house:

The glass was poured into a mold, I guess, that made the base and bowl, which are in one piece; the glass is thick and clean, with icy lights in it. The base is a simply fluted, hollow skirt; stands on the table; is solidified in a narrowing, a round inch of pure thick glass, then hollows again, a globe about half flattened, the globe-glass thick, too; and this holds oil, whose silver line I see, a little less than half down the globe, its level a very little—for the base is not quite true—tilted against the axis of the base.

If you turn to the front of the book, you can see the lamp he’s talking about and verify his description of its shape and its tilt, in a Walker Evans photo, which, like many of the photos that Evans took of Alabama’s tenant farmers, is also available in a high-resolution scan at the Library of Congress. Agee describes the graniteware washbasin visible in the same photo toward the end of “A Country Letter” and again in a later section titled “The hallway; Structure of the four rooms.” In the section “Shelter,” he gives a lengthy ekphrasis of a decorated mantelpiece at the Burroughses’, down to the whitewash print of a child’s hand to one side of it. In Evans’s photo, available at the Library of Congress and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s also some graffiti above the mantel, unmentioned by Agee. I wasted some time trying to decipher it from the high-quality scan, but without success. Any guesses?

If you turn to the front of the book, you can see the lamp he’s talking about and verify his description of its shape and its tilt, in a Walker Evans photo, which, like many of the photos that Evans took of Alabama’s tenant farmers, is also available in a high-resolution scan at the Library of Congress. Agee describes the graniteware washbasin visible in the same photo toward the end of “A Country Letter” and again in a later section titled “The hallway; Structure of the four rooms.” In the section “Shelter,” he gives a lengthy ekphrasis of a decorated mantelpiece at the Burroughses’, down to the whitewash print of a child’s hand to one side of it. In Evans’s photo, available at the Library of Congress and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s also some graffiti above the mantel, unmentioned by Agee. I wasted some time trying to decipher it from the high-quality scan, but without success. Any guesses?

In his collaboration with Agee, Evans was funded by the government’s Farm Security Administration, and the copyright of his photos are now owned by the public and many of his original prints are in the care of the Library of Congress. In addition to individual photos, the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division has digitized two albums, containing slightly more than a hundred prints (update: this is now a better link, that Evans assembled to document his trip with Agee. (If you click on one of the albums at the top of the page, you can then flip through it in an online reader page by page.)

Most of the photos that Agee glosses are printed in the front of his book, and a few more may be found online in the Library of Congress’s two albums. To find still more photos, search the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division for ‘Walker Evans Alabama’ or for ‘Walker Evans’ and the name of one of the tenant-farming families (‘Burroughs’, ‘Tingle’ [sometimes spelled ‘Tengle’], or ‘Fields’). Once you do this, click on ‘Display Images with Neighboring Call Numbers’ if you want to see Walker Evans photos in the Library of Congress that haven’t been given titles or otherwise indexed. That’s the only way to find this portrait of the children Floyd Lee Burroughs Jr. and Othel Lee Burroughs, this alternate portrait of Floyd Burroughs on his porch or this one of him on a mule, or this enigmatic close-up of one of the Fields children.

Most of the photos that Agee glosses are printed in the front of his book, and a few more may be found online in the Library of Congress’s two albums. To find still more photos, search the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division for ‘Walker Evans Alabama’ or for ‘Walker Evans’ and the name of one of the tenant-farming families (‘Burroughs’, ‘Tingle’ [sometimes spelled ‘Tengle’], or ‘Fields’). Once you do this, click on ‘Display Images with Neighboring Call Numbers’ if you want to see Walker Evans photos in the Library of Congress that haven’t been given titles or otherwise indexed. That’s the only way to find this portrait of the children Floyd Lee Burroughs Jr. and Othel Lee Burroughs, this alternate portrait of Floyd Burroughs on his porch or this one of him on a mule, or this enigmatic close-up of one of the Fields children.

Still more images may be found at the Walker Evans Archive of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it’s easy to compare the stoic close-up portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs (Annie Mae Gudger) that Evans chose to print in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men with her sly smile in two variants. (Here’s yet another, from the Library of Congress, which was reproduced in Evans’s American Photographs of 1938.) The Met also has a striking image of Floyd Burroughs in profile, which I’ve never seen anywhere.

Though the photographic archive is abundant, there are intriguing lacunae. A few times, Agee describes photos taken by Evans that don’t seem to correspond to images available anywhere online or in any publication that I’ve looked in. At the bottom of page 364 and top of page 365, for example, Agee describes a picture of the Ricketts (Tingle) family thus:

there you all are, the mother as before a firing squad, the children standing like columns of an exquisite temple, their eyes straying, and behind, both girls, bent deep in the dark shadow somehow as I listening and as in a dance, attending like harps the black flags of their hair

Perhaps Agee is describing the original from which Evans cropped this image? (There’s a better version at image 24 of the second of the two albums mentioned above; update: here’s a better link.) It’s impossible to know.

There’s another ghost photo on page 369, when Agee describes a family portrait of the Burroughses:

The background is a tall bush in disheveling bloom, out in front of the house in the hard sun: George [Floyd] stands behind them all, one hand on Junior’s shoulder; Louise (she has first straightened her dress, her hair, her ribbon), stands directly in front of her father, her head about to his breastbone, her hands crossed quietly at the joining of her thighs . . . ; Burt sits at her feet with his legs uncrossing . . . ; and there again they are; the three older of them thoroughly and quietly serious, waiting for the shutter to release them . . .

I have no idea where this image is, if it survives. At least one Evans portrait of the Gudgers/Burroughses as a family does survive. It’s reproduced on the cover of William Stott’s Documentary Expression and Thirties America, and is held by the Walker Evans Archive at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, source of the image to the right. As you can see, though, the family is standing in front of their house in this image, not in front of a bush, and the configuration of persons is slightly different from what Agee describes.

I have no idea where this image is, if it survives. At least one Evans portrait of the Gudgers/Burroughses as a family does survive. It’s reproduced on the cover of William Stott’s Documentary Expression and Thirties America, and is held by the Walker Evans Archive at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, source of the image to the right. As you can see, though, the family is standing in front of their house in this image, not in front of a bush, and the configuration of persons is slightly different from what Agee describes.

Toward the end of his book, Agee describes images of a naked infant boy and naked infant girl, but it isn’t clear from his wording whether the images were photographed by Evans or existed only in Agee’s mind’s eye. In any case, it seems likely that someday even more photographs by Evans of the families in Agee’s book may turn up, perhaps in the form of negatives that the Library of Congress has yet to digitize. In conclusion, and just for the hell of it, here’s a link to a funny picture of Evans himself, taken by the great Helen Levitt, which was recently donated to the Museum of Modern Art.

Silence and Song

Childhood, an early short film by Terence Davies, tells the story of Robert Tucker in two phases: as a boy growing up in an unhappy family in Liverpool and as a young man who has just barely survived it. The best thing in the movie is a long scene on a bus. It begins as a flashback. Robert Tucker, as a young man, has just visited a doctor who has prescribed him medication for depression and has asked whether he’s developed any interest in girls yet. He hasn’t. He walks to a bus stop, where a couple of young women titter at his doleful looks, and before the bus comes, there is a flashback: Robert, as a boy, is boarding a double-decker bus with his mother.

“Can we sit inside?” the boy asks. This tells us something about the boy; he’s the sort who thinks it’s more of a treat to sit inside a double-decker than on top. The boy’s mother is played by a woman with attractive features but hollow eyes. The two sit down, he in a window seat, she in an aisle seat beside him so that she is closer to the camera, and the bus pulls away. They don’t say anything further; they don’t look at each other. She stares at the middle distance. He watches the streets of Liverpool pass by. The camera stays on them. Rows of workers’ housing roll past; a corner is turned; more rows of similar housing roll past. The camera still does not move. It begins to occur to the viewer that this is not a scene that sets up another scene, despite its apparent lack of event. After a long while, the mother quietly cries. The boy does not try to comfort her; the viewer senses that an “interaction” of any kind would be false. Mere presence is as much as the mother and the boy are able to give each other.

There are a number of parallels between Childhood and Davies’s later, full-length film The Long Day Closes. Both seem to be autobiographical. Both portray a boy who says “thank you” to school authorities when they whip him across the palm, who is awkward in the school swimming pool, who is set upon by bullies, and who will, we understand, grow up to be gay. Even the layout of the family home in both movies is the same. But The Long Day Closes is a warmer film—a film so full of love, in fact, that it’s almost painful to watch—and there are important differences. It’s in color, for one thing, and it has a sense of humor, for another, complete with Dickensian minor characters such as a plethoric, henpecked husband who does flawless impressions of Jimmy Cagney and Humphrey Bogart. In the later movie, the parallel to the Childhood bus scene takes place at home. The hero, a young boy named Bud, is sitting beside his mother. Their faces are lit by a fire, not visible. She sings a song while looking into it. As with many of the songs in the movie, the gender of its persona conflicts with that of the singer, and so the mother explains, when she finishes, that it was her father’s song—he used to sing it to her when she was a girl. She begins to cry as she explains this, and the boy, though he seems to be listening intently, continues to stare straight ahead into the fire, almost as if he doesn’t notice her grief. There is no need for him to notice it, we sense; he is at one with her; he feels her sorrow as if it were his own, because the song and her touch have communicated it to him, and have also communicated the strength and the beauty that he will need in order to bear it. In Childhood nothing was in the place of song. Literally nothing: it was through silence and the absence of touch that Robert’s mother communicated to him.

Silence and song are not so different. The matter of both is time; neither is intelligible unless you can hear rhythm. In watching Childhood the viewer has the sense that what was communicated was so sad, so heartbreaking that it could do violence to Robert. It hurt him as a boy, and it might kill him as a young adult, in the form of a depression he can’t understand. What’s shared is just as sad in The Long Day Closes. Perhaps it’s even sadder. The trouble in Childhood, after all, seems to be that love is sometimes met by cruelty, and the trouble in The Long Day Closes is that those we love, and who love us, will in time die. But Bud is able to bear the greater grief in The Long Day Closes because his mother’s sorrow comes to him as part of the company she offers. It is a further sweetness. And so Bud does not grow up to be a fragile or a brittle man. He grows up to be the maker of the film The Long Day Closes, whose presence is so palpable in the film that he should perhaps be thought of as a character in it.

Almost every detail in the movie reminds the viewer that he is watching a movie not life. The rain—and there is a lot of rain—is always movie rain. When at Christmastime the camera pans slowly away from a family tableau into the darkness down the street, the darkness is streaked with not real snow but movie snow, meteoric and fanciful. When Bud daydreams in class of a ship in a storm, and we see the ship, it is patently a model ship, photographed in close-up. None of this artifice lessens the movie. It is a kind of understatement. It is part of the director’s way of speaking: It was like this, but of course all I can show you is a movie.

He communicates to us not with spectacle, that is, but the way his mother communicated to him, through silence and song. The silence has become famous. There is a long scene in The Long Day Closes when the camera rests on a carpet while sunlight shifts there. When I first saw the movie, in 1993, this scene frightened me. I remember worrying whether the friends beside me would grow impatient. They had brought me to the movie, but I was falling in love with it, and the scene made me worry that I would need to protect the movie from them. It made me feel how attached I was to it. It made me realize that I didn’t mind sitting with it for a long time while nothing appeared to happen. The scene is a little like staring out the bus window while your mother is crying beside you and you are trying to allow her her privacy. And it is a little like noticing how beautiful even the most trivial and casual thing is, once love has attached you to the world it is a part of. To some it will seem like poverty, and to others, like enormous wealth.

Sun shifting on a carpet: light moving on a screen. When the camera at last rises from the carpet, it goes to Bud, kneeling in the sill of a window so that he can stare through it, the lace curtain draped over him like some kind of ritual vestment. It is largely by looking through windows that Bud turns life into a movie that he is watching. Sometimes the window is open and the sun is shining, as when he watches a shirtless bricklayer, who winks and embarrasses him. (In Childhood and its two sequels, Robert’s sexuality was sometimes a heavy-handed matter, and its punishments were sometimes melodramatic. In The Long Day Closes, in contrast, the workman’s wink is the only direct acknowledgment.) Sometimes rain is streaming down the window’s glass, softening the light, rendering it more complex, as if the glass had come alive. Rain also destroys, however. In geology class, Bud learns about erosion, and from David Lean’s Miss Havisham, whose words come to Bud after a friend betrays him by going to the movies with another boy, he learns that decay is the fate of those who can’t find love. In the very first scene of the movie, for that matter, we see under rain the ruins of the world we are about to enter. It existed in time only, not in eternity. It existed in silence and in song. Bud’s mother sang about the loss of her father to him, but Bud will have no children to whom he can sing the loss of his mother and the world he shared with her. Instead there is just a movie, radiating outward like the flashlight that Bud shines into the sky one night, after being told in school that such a light will go on forever, and which Bud turns, finally, into the lens of the camera, canceling it.