"It Happened One Decade," my review-essay focusing on Morris Dickstein's Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression, is published in the 21 September 2009 issue of The New Yorker. The book under review is a genial and comprehensive guide to the literature, film, and music of the nineteen thirties. Though I often post an online bibliography of my New Yorker articles, there's not much call for one in this case, since almost all the books that I refer to in my review are cited by author, title, or both. Instead, in the next couple of posts, I'll try to write about oddments that I couldn't find a place for.

"It Happened One Decade," my review-essay focusing on Morris Dickstein's Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression, is published in the 21 September 2009 issue of The New Yorker. The book under review is a genial and comprehensive guide to the literature, film, and music of the nineteen thirties. Though I often post an online bibliography of my New Yorker articles, there's not much call for one in this case, since almost all the books that I refer to in my review are cited by author, title, or both. Instead, in the next couple of posts, I'll try to write about oddments that I couldn't find a place for.

Category: literature

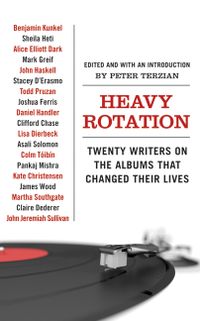

Heavy Rotation, the debut and the parties

My boyfriend, Peter Terzian, has edited an anthology that Harper Perennial is going to publish on June 23: Heavy Rotation: Twenty Writers on the Albums that Changed Their Lives. It features the following pair-ups:

My boyfriend, Peter Terzian, has edited an anthology that Harper Perennial is going to publish on June 23: Heavy Rotation: Twenty Writers on the Albums that Changed Their Lives. It features the following pair-ups:

- Stacey D'Erasmo on Kate Bush,

- Pankaj Mishra on ABBA,

- Colm Tóibín on Joni Mitchell,

- Mark Greif on Fugazi,

- Sheila Heti on the Annie soundtrack,

- Ben Kunkel on the Smiths,

- James Wood on the Who,

- John Jeremiah Sullivan on early blues,

- Clifford Chase on the B-52s,

and quite a few more. In my opinion, it is the book of the year. Kirkus, perhaps a more neutral judge, calls it "Music writing with a personal twist by an assortment of modern writers. . . . A satisfying, fun read that may prompt rifling through old CDs and LPs to reclaim one's own transformative musical memories." You can order your copy now on Amazon, on Barnes & Noble, or through Powells.

And if you're in New York City this summer, you're invited to some parties in its honor, which promise to be pretty amazing, especially if you have a taste for lounge-singing book editors and bongo-drumming literary critics. Here's the schedule, courtesy of Peter:

- Tuesday, June 23rd, 7:00 pm

Heavy Rotation launch party

Come have a drink, meet the contributors, and celebrate the book's publication day.

At Book Court, 163 Court Street between Dean and Pacific Streets, Brooklyn - Wednesday, July 1st, 12:10 pm

A lunch-hour event in Bryant Park, behind the New York Public Library. Editor Peter Terzian will be discussing music and writing with contributors Clifford Chase, Stacey D'Erasmo, Joshua Ferris, and Asali Solomon. Plus, the New York debut of contributor John Jeremiah Sullivan's band Fayaway, with special guest percussionist James Wood.

Note: Fayaway will play two sets—one at 12:10, before the discussion, and another at 1:30, after the discussion. The discussion will begin at 12:30.

At

Bryant Park Reading Room, New York (near 42nd Street, between the back of the library and 6th Avenue—look for the burgundy and white umbrellas) - Tuesday, July 14th, 7:00 pm

Contributors Lisa Dierbeck, John Haskell, Todd Pruzan, and Martha Southgate will join me in a reading and panel discussion. With musical accompaniment by cabaret singer (and the book's Harper Perennial editor) Rakesh Satyal.

At McNally Jackson, 52 Prince Street between Lafayette and Mulberry Streets, New York

No RSVP required. See you there!

Meaulnes’s romance

In The Magician’s Book, her lovely, impassioned account of the Chronicles of Narnia, my friend Laura Miller suggests that the magic of C. S. Lewis’s books may owe more to medieval than to modern sensibilities. She points out that in his scholarship, Lewis defended medieval literature from the condescension of twentieth-century critics, who sometimes saw it as crudely allegorical. In fact, Lewis insisted, it was these critics’ understanding of medieval allegory that was crude. Writes Miller:

What made allegory powerful, and in Lewis’s eyes “realistic,” is that it was a sophisticated way of representing the inner lives of human beings at the time the great allegories like The Romance of the Rose were written. Though we now take for granted the notion of psychologically conflicted characters (who are “torn” or “divided” by forces contained within their own hearts and minds), the medievals didn’t have an artistic and conceptual toolbox quite like our own. Instead of imagining each person as possessing a complex interior mental space full of warring impulses, their picture of character was more external. So for them the natural way to portray what we would regard as a debate within a person’s psyche would be to write a passage in which a figure labeled (for example) Reason stands in a garden quarreling with a figure called Passion. . . . In a true allegory, where aspects of a woman’s personality are made to walk about and otherwise behave like independent people, the woman herself—the territory on which the conflict is being played out—becomes a physical space, a plot of land. The medieval self is, in this sense, geographical.

In later chapters, Miller suggests that Lewis’s Narnia books are romances, not novels, and belong to an alternative tradition that includes not only J. R. R. Tolkien and William Morris but also Dante, Thomas Malory, and Edmund Spenser. After crediting the critic Northrop Frye for the categories, Miller writes that “Most romance . . . belongs to youth and speaks to the desire to get out in the world and prove oneself, which may be why the form proliferates most luxuriantly and in some of its purest strains in children’s fiction.”

Recently, I read a book that turned out to be a romance, though I wasn’t expecting it to be one. When I began Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes, first published in 1913, I thought it was going to be about French schoolboys. The narrator, François Seurel, opens by looking back to a November day in the 1890s when he was fifteen years old and studying to earn his teaching certificate at a school where his father was headmaster. In describing the day that a new boy arrived at the school, Seurel’s tone is wistful, a little melancholy:

He arrived at our house one Sunday in November, 189…

I still say “our house,” even though the house no longer belongs to us. We left that part of the country almost fifteen years ago and we will surely never go back to it.

The new boy’s arrival coincides with Seurel’s recovery from a childhood hip disorder, which all but crippled him and left him shy and quiet. The new boy, Augustin Meaulnes, is in perfect health and is two years older than Seurel. Because of his height, the boy is soon to be nicknamed by his classmates “le Grand Meaulnes,” Tall Meaulnes (which sounds more cryptic in English than in French, and so in English the book either bears its French title or another one altogether). Meaulnes is also a little wild. Even before Mme. Meaulnes has settled with Seurel’s parents on the terms for boarding her son, Meaulnes finds in the Seurels’ attic two as-yet-unexploded fireworks and detonates them in the schoolyard as Seurel stands by. Seurel describes himself as “holding the tall new boy by the hand and not flinching.” Meaulnes, who reminds Seurel of a young Robinson Crusoe, is to be his guide into risk and adolescence.

Such a commencement doesn’t necessarily promise romance in C. S. Lewis’s sense of the word. The story of a mild boy looking up to a bolder one could be told novelistically, with a very modern psychology. But even in these opening chapters, it’s evident that Alain-Fournier isn’t a psychologist of that sort. Seurel describes his crush on Meaulnes without any embarrassment; he isn’t in any conflict about it. Nor is Meaulnes in any conflict about his wildness. He never apologizes when he breaks the rules set by Seurel’s father; he certainly never shows any signs of feeling guilty. For their part, Seurel’s parents are never petulant about Meaulnes’s behavior. Everyone treats everyone else with a kind of plainness and straightforwardness that is probably the first sign that this is a romance and not a novel. The second sign comes when Meaulnes runs off one day with a horse and carriage, becomes lost in the countryside, and, following a stone tower, stumbles into a ruined castle where he is invited to join a strange pageant, performed entirely by children . . .

To say much more would give too much away. The charm of the book is that it moves from realism to romance (and back again) without acknowledging any incommensurability between the genres. The people that Meaulnes finds in the castle are human; the bewitchment of the place is not by magic but by a kind of family history. But if, as Miller writes, “the medieval self is geographical,” then Meaulnes’s self is medieval, and so is Seurel’s, because the two boys will struggle with their geographic knowledge of the castle, or rather geographic ignorance of it, for the rest of the book. As in Lewis’s romances, all the characters find doubles, and in some cases triples. These doubles aren’t named Reason and Passion, or Childhood and History, or Wealth and Poverty, but they have the same internal simplicity and interactive complexity that Lewis, in Miller’s paraphrase, credits to allegory. By the end, there is nothing childish about the story at all, except insofar as the tragedy of adult love is one first perceived in childhood.

Rad tot lit

"Children of the Left, Unite!" my essay about Tales for Little Rebels, an anthology of radical children's literature edited by Julia L. Mickenberg and Phlip Nel, appears in the 11 January 2009 issue of the New York Times Book Review.

An afterthought: Though, as you will see if you read my essay, the play about the beavers left me cold, I learn from Vicky Raab, writing at the New Yorker's Book Bench blog about Sally Quinn's new history of the WPA theater, that when it was staged with roller skates in the 1930s, it seemed "so thrilling that it incited children to rush the stage." De castoribus* non est disputandum, evidently.

* Declension corrected! A proper Latinist points out that not the genitive but the ablative is required here.

Boom

In Bookforum, Craig Seligman, author of the brilliant Sontag and Kael, wonders what to make of the sexual revelations in the first volume of Susan Sontag's journals, which he likens to an explosion and which, like me, he finds "riveting":

So, surprise—she was human. The inverse parabola that Reborn traces—the high of her sexual initiation, the low of her marriage, and her eventual reawakening (her real rebirth)—constitutes a gay-liberation paradigm so obvious it borders on the banal. Except that, as we all know, the story didn’t end so crisply. Sontag came no further out of the closet before the wider public until she was forced to by a pair of hostile biographers in 2000. There’s been endless speculation as to why she remained so tight-lipped. A lot of people have called her a coward.

I don’t think there was anything cowardly about her, though. It was more complicated than that. Her sexuality wasn’t what she wanted the conversation to be about—and she always thought she could control the conversation.