I was interviewed about Moby-Dick for a podcast the other day (keep an eye out for an episode of The World in Time, from Lapham’s Quarterly), which triggered a re-reading. I think this was my sixth time through? I am now the age of Ahab, who, in chapter 132, tells Starbuck that he started whaling as “a boy-harpooneer of eighteen” and has spent “forty years on the pitiless sea.” I, too, have reached my implacability-and-fixed-purpose era. (Or would like to have reached it. That third novel would be getting written faster, if I had.)

I think I was invited on the podcast because I’m a bit of an oddity, someone who managed in the end to turn himself into a general “writer” but started as a Melvillean. In an earlier life, I wrote for scholarly journals and university presses about such topics as Melville’s conflation of cannibalism and homosexuality, the trick sanctification of sacrificed gay desire in Billy Budd, and the Platonic erotics of mining for sperm at sea.

I happen to be re-reading Emerson’s journals, for no particular reason, and along the way I have been jotting down what amounts to a haphazard collection of entries that prefigure Melville. Some are pretty uncanny. For example, a dozen years before Melville’s debut novel Typee, which fictionalized his experience of jumping ship to live among islanders who might or might not have been thinking of dining on him, Emerson wrote in his journal: “In the Marquesas Islands on the way from Cape Horn to the Sandwich Islands, 9° S. of the Equator they eat men in 1833.”

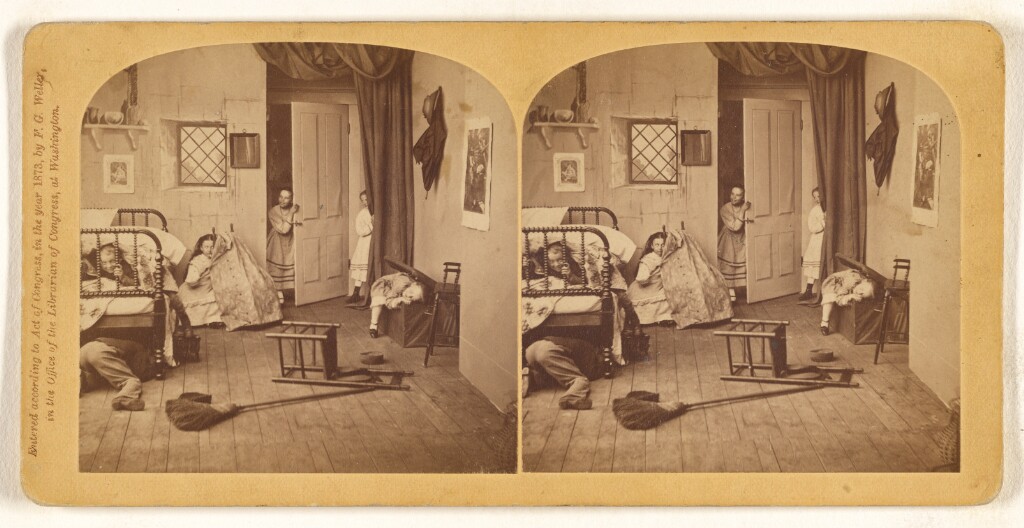

A few days later, Emerson records a night in a hotel that foreshadows the meet-cute of Ishmael and Queequeg:

I fretted the other night at the Hotel at the stranger who broke into my chamber after midnight claiming to share it. But after his lamp had smoked the chamber full & I had turned round to the wall in despair, the man blew out his lamp, knelt down at his bedside & made in low whisper a long earnest prayer. Then was the relation entirely changed between us. I fretted no more but respected & liked him.

Prayer helps reconcile Ishmael and Queequeg, too; shortly after they get married, as you may recall, Ishmael joins Queequeg in worshipping his idol, Yojo.

Father Edward Taylor, the seamen’s minister, who was the real-life model for Melville’s character Father Mapple, was a friend and colleague of Emerson’s, and stayed over at his house at least once. In June 1835, while mulling over whether he should still call himself a Christian, Emerson declared, “But if I am the Devil’s child, I will live from the Devil,” a passage that reminds me of Ahab seizing a lit-up lightning rod in chapter 119 and avowing himself a child of the unholy electric fire.

Maybe the most remarkable prefiguration comes on 19 February 1834, when Emerson reports that

A seaman in the coach told the story of an old sperm whale which he called a white whale . . . who rushed upon the boats which attacked him.

Emerson was living in a Melvillean world.

What’s it like to read Moby-Dick when you’re Ahab’s age? There are probably a number of things I no longer see as acutely as when I had young eyes, but some elements are now in sharper focus. When young, I had only the vaguest sense, in any given chapter, where Ishmael was, geographically speaking. For me then, the important seas to be swimming through were of metaphor and feeling. Now I see that Melville is actually pretty careful to map the Pequod’s journey; in late middle age, my internal GPS module keeps better track of where I as a reader am supposed to be—so much better track that it’s a bit of a comedown to realize that the epic events of the novel happen in specific actual places, not just in elemental spheres.

At this point, I’ve read pretty much every word of Melville’s that has survived, so another thing I can’t help but notice is the way Melville prefigures himself in Moby-Dick. For example: In one of his prefatory chapters, Melville presents a series of quotes about whales and whaling. One of these is taken from an account of a mutiny aboard the whaleship Globe, and reads, “‘If you make the last damn bit of noise,’ replied Samuel, ‘I will send you to hell.'” Next to this extract, a younger me wrote in the margin, “& the relevance to whaling?” (in his defense, young me went on to speculate a not-implausible link to Hobbes’s Leviathan). I don’t have any trouble seeing the relevance today. It seems obvious to me now that mutiny is implicit everywhere in the novel, that Billy Budd is already present in Moby-Dick, as an undertext. (Mutiny and Billy Budd were also present in White-Jacket, the novel that came just before Moby-Dick.) In chapter 123, mutiny becomes explicit, when Starbuck raises a musket and then, weakly, lowers it. Starbuck is a good hero who can’t get angry enough to rebel, much as Billy Budd is the Handsome Sailor who can’t bring himself to say plumply no, until his fist flashes out. Starbuck’s fist never does. He’s the classic liberal, without quite enough thumós to take out the madman before it’s too late. Mutiny pretty much has to be an issue aboard the Pequod; the search for energy, after all, is classically the locus where force supervenes in politics and economics—where need and power override contracts and consent.

Other prefigurations: In their gams, the whaleships in Moby-Dick trade letters, sometimes addressed for sailors who have already perished, a foreshadowing of the Dead Letter Office that was Bartleby the scrivener’s previous place of employment. And in the contrasting plights of the sperm-filled whaleship Bachelor and the bone-dry Jungfrau, there seems to be a precursor to the “joke”/schema of Melville’s paired stories “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids”—a joke that now seems pretty ponderous to me, unfortunately, however laden it may be with homoerotic significance.

When you read Moby-Dick as an undergraduate, and you come across a reference to, say, a Bible verse you haven’t heard of—such as, in chapter 95, Melville’s reference to 1 Kings 15, which describes, Melville says, an idol “found in the secret groves of Queen Maachah in Judea; and for worshipping which, king Asa, her son, did depose her, and destroyed the idol, and burnt it for an abomination at the brook Kedron”—you think to yourself, Huh, well, we didn’t learn that verse in Sunday school, but I bet it’s the sort of thing a well-read person in the 19th century would have known about and recognized. Or, you read Melville’s comparison of the white whale to an anti-deity worshiped by “the ancient Ophites of the east,” or his comparison of the dark depths of Ahab’s soul to the undercellar of the Hotel de Cluny and to “the Roman halls of Thermes,” and you think, Everyone must have been so much more learnèd in Melville’s day! They must have had all these esoteric religious and archeological references at their fingertips. Well, maybe. But I’m as grown-up now as I’m likely to get, and have read an awful lot of 19th-century prose, and I think undergraduates can be forgiven for not getting all of Melville’s references. My sense is that some of Melville’s points of reference were pretty obscure, and would have been even to educated peers of his. Which isn’t that surprising. Melville was an autodidact. His picture of the cultural world is one he had to draw for himself, and what he came up with can be a little quirky, as is often the case with autodidacts. Especially quirky, with Melville, are the departments of theology and anthropology. Somewhat surprisingly, he actually seems pretty canonical where whaling is concerned; my sense is that most whaling nerds of his day would have agreed that the whaling books he mentions are the important ones.

The last thing that strikes me strongly on this re-reading: Moby-Dick is not built the way novels are supposed to be. It’s not surprising that most people who attempt the novel lose their oomph somewhere around page 100. Novels usually hold your attention with little loops and twists of plot. Clara and Guillaume have become engaged to marry, but after Soren returns from his apprenticeship in Rome, Clara remembers all that Soren used to mean to her, and for some reason becomes willing to believe Soren has reformed, as he claims, although Guillaume has by chance found out that Soren is not only still partial to gaming but also saddled with ignominious debt, and yet it would be ungentlemanly for Guillaume to betray Soren’s confidence to Clara; the only noble thing to do is wait out patiently the rekindling and eventual subsidence of her infatuation—there is nothing like any of this in Moby-Dick. Instead: sailors get on a doomed ship. They agree to hunt a white whale. Everyone knows it is going to end badly. Everyone knows this pretty much from the start. There is a romance plot, but no sooner is it sparked than it dives, far beneath narrative. Ishmael and Queequeg are married in chapter 10 (of 135), but once they board the Pequod, you pretty much never hear about their love, or any of its vicissitudes, ever again, unless you count the very late resurfacing (sorry, spoiler!) of Queequeg’s coffin, which becomes Ishmael’s life buoy. And there’s not really anything that takes the place of this submerged romance plot. There is no other novelistic “business.” Nothing ever seriously threatens to derail Ahab from his mission, for example; there’s not any back-and-forth of hope raised and then dashed. The novel’s plot is a straight line—interrupted, for a span of about 350 pages, by fairly allegorical episodes of whale-hunting, and fairly metaphysical essays about whales. I still think Moby-Dick is brilliant, don’t get me wrong, but it’s brilliant as a meditation on representation, and incarnation, and the problem of having a soul that’s inside a body, and necessarily dependent on, and sometimes antagonistic to, other bodies, which apparently have souls inside of them, too, and of living in a world that is said to have been created by a deity but doesn’t have all that much in it in the way of the grace and mercy that a benevolent deity could be counted on to supply. Moby-Dick is not brilliant in the way of, say, Middlemarch, which is the novel I’m re-reading now, where characters have different kinds of interiority and purpose, and project onto one another and frustrate one another and discover they have feelings for one another they weren’t at first aware of. Ishmael is almost too ironic about himself to have interiority, of the George Eliot sort. In Moby-Dick, only Ahab has rich interiority, and he’s insane. And the reader accesses his interiority through his soliloquies and through Melville’s complicated prose gestures towards him, not through the eavesdropping that free indirect discourse makes possible.

In Moby-Dick, a young, great, unruly, and untrained mind is wrestling. In chapter 42, for example, as Melville piles up associations and allusions that might help explain the meaning of the whiteness of the white whale, he notes that “the great principle of light . . . for ever remains white or colorless in itself, and if operating without medium upon matter, would touch all objects, even tulips and roses, with its own blank tinge.” Two chapters later, describing an episode that Ahab goes through of what sounds like depersonalization, maybe as a component of a panic attack, Melville tries to describe what it’s like to be conscious without a self, writing that “the tormented spirit that glared out of bodily eyes, when what seemed Ahab rushed from his room, was for the time but a vacated thing, a formless somnambulistic being, a ray of living light, to be sure, but without an object to color, and therefore a blankness in itself.” Did Melville realize he was echoing his earlier paragraph? The novel is full of what scholars call “unemendable discrepancies” and “unnecessary duplicates”—scribal errors that are impossible to yank out of the book’s semantic fabric. Maybe this echo, too, is an error, or maybe, to look at it more generously, Melville became aware, as he wrote, that he was repeating that idea that light, which bestows color, itself has no color—and doubled down. Maybe the “mistake” of repetition, as he made it, began to suggest a meaning he couldn’t bring himself to discard. I don’t think Melville is someone who ever killed his darlings. It’s hard to winkle out exactly what this particular “mistake” means, and it’s equally hard to imagine that Melville intended to make it before it, as it were, happened to him, in the heat of writing. Still, the suggestion made by the error is ingenious: that there is a parallel between the horror that the white whale inspires, through being the no-color of light itself, and the horror that not-Ahab experiences, when the self of Ahab is no longer coloring not-Ahab—that there is something terrifying about unqualified, unmediated existence, more real and more powerful than the appearances that we usually live as and among.