In connection with my new short story in The Paris Review, I wrote a short essay about Raymond Carver and the Pet Shop Boys for Redux, the Paris Review’s newsletter about revisiting its archives. I believe the newsletter with my essay in it is going to go out this weekend, so if you’d like to read it, sign up for Redux here!

Category: gender

Time to Let Go

Also available as an issue of my newsletter, Leaflet

Top Gun: Maverick opens with Tom Cruise sitting in a chair, out of character. He thanks the audience for leaving their homes to experience the movie on a big screen. When Peter and I went to see Maverick in a movie theater, the other night, I was surprised by how old Cruise looked. He’s much better preserved than most civilians, of course, but in an age of motion capture and CGI, it’s a choice for a star like Cruise to allow his age to be visible. It occurred to me that the movie’s preface might have an ulterior purpose: to give the audience a moment to adjust to what time has done to the man who has long played the hero of their fantasies.

Cruise’s age is decidedly diegetic in the movie that follows. His character, Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, is still flying planes for the Navy, more than three decades after the fictional events of the first Top Gun movie, and Maverick’s persistence in his vocation is understood, within the movie’s storyline, to be both failure and success. Failure, because Maverick is still just a captain all these years later, having refused to, or having proved unable to, accommodate himself to the military as an institution. Success, because, after three-plus decades of just flying planes, he’s very good at it. The ambiguity shrouds Maverick the way his black leather jacket does. It’s the same kind of jacket he would have worn more than three decades earlier—maybe it’s even the very same jacket—and we remember how in those days it seemed to participate in his virility. On a man in his fifties, however, an article of clothing that was archetypally sexy a generation ago has a certain pathos. (I say this as a man in his fifties.) Cruise looks great, but the jacket and the teardrop-shaped aviator sunglasses that go with it remind us so sharply of what Cruise looked like thirty-six years ago that they accentuate the contrast with his earlier physical self. We’re meant, I think, to feel a little sorry for him for still trying, and to feel bad that we feel that way. Which is, unexpectedly, a gentle feeling.

Top Gun: Maverick turns out to be a longitudinal movie, one that plays on and with the passage of time as it can be seen telling on the bodies of its actors, like Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, Before Midnight, and Boyhood; François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel movies; and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return. In this class of movies, there can be moments of almost unbearable poignancy, exceeding the usual aesthetic frame around a movie. The passage of time can seem to be collapsing as one watches. A great role is a vital moment in the life of an actor, and when an actor revisits such a role, the viewer is aware of watching not only a fictional character’s resurrection but also a real person confronting a work of art that he may have thought at the time that he was the master and creator of, but which, in the years since, he has probably come to realize he was shaped by in ways he could never initially have intended, no matter how consciously he then thought he was working.

The first essay I ever wrote for my blog was about the original Top Gun. Peter and I watched it on a DVD mailed to us by Netflix, in April 2003, neither of us having seen it during its 1986 release, when we were teenagers. Peter now has no memory of having watched it at any time, but I looked my old essay up on my phone the morning after we saw Maverick. I was so angry in 2003! I wrote so knowingly! I seemed so certain of the points I was scoring against my enemy, whoever that was! Maybe a blog can be longitudinal, too? It was all so long ago.

In the spring of 2003, America was invading Iraq for the second time, and Top Gun was already an old movie, time-traveling from an America that hadn’t gone to war for a generation and was on the verge of discovering that it had a hankering to kill again. By 2003 America had consummated that desire, and I was angry, I think, because the Top Gunof 1986 seemed to me to have done what Marxians call ideological work toward that end. My theory seems to have been that the movie had whetted an appetite for violence by manipulating its male viewers’ anxieties about inadequacy and about having feelings for other men that were too strong. It was hardly a reach for me to come up with such a theory. In those days, to justify the U.S. military’s don’t-ask-don’t-tell policy, psychologists like Charles Moskos theorized something similar. It was understood that very few soldiers are willing to die for something as abstract as a nation and in practice risk their necks only for the other people in their unit whom they have become close to. Moskos thought open homosexuality would interfere with what he called unit cohesion. The military needed for soldiers to feel close but not in that way. If they started making love to each other, they would stop loving one another.

The year 2022 calls for different ideological work. America has lost its appetite for war. In fact it no longer has the stomach to digest the ones it’s still fighting, and consequently there is little discussion by journalists, and virtually none by politicians, of what we’re doing in Somalia, where we recently increased our military presence, or of our ongoing complicity with war crimes and humanitarian catastrophes in Yemen. In 2003, I thought Top Gun was a movie about short-circuiting mourning in order to induce a mindset more amenable to killing. Maverick, however, is just a movie about mourning. Period. Which isn’t to say it’s honest; more on its disingenuousness in a moment. But despite that disingenuousness, it is, surprisingly, a movie about decline and loss, visible from the movie’s very first frames in Cruise’s weathered face. Val Kilmer also reprises a role from the first Top Gun movie, and Kilmer, who in real life is recovering from throat cancer, is even more cruelly changed by time. His character tells Cruise’s, at one point, “It’s time to let go.” Cruise resists, of course, and the movie’s highs, which are considerable—I won’t pretend I didn’t enjoy the ride, and I even recommend it—stem from the fantasy that a man in late middle age can have one last hurrah. I think the viewer is meant to experience the hurrah on the screen as fantasy; I think the movie wants the viewer feel that Kilmer is right, that the end is coming, that, in fact, it’s pretty much here.

The sequel gestures toward rehearsing the neoliberal sermons about masculinity preached in the original. In Top Gun, the danger was that Cruise would feel too guilty about not having saved his fellow aviator Nick “Goose” Bradshaw to make a good soldier. In Maverick, the corresponding character flaw, which the screenwriters have given Goose’s son, Bradley “Rooster” Bradshaw, is a tendency to “overthink,” to delay firing until sure everything will work out. Which isn’t on the same level at all. In an early scene in a bar, a new generation of young aviators mock Cruise as “Pops” in a jolly hazing, tossing him out to the street when he can’t pay his bill. In Top Gun, it was Cruise’s short stature that signaled that he was a beta struggling in a world of alphas; in Maverick, it’s his age. In both movies, his smile encodes his survival strategy—submission without deference. Cruise is able to make being thrown out of a bar look like crowd-surfing. There’s no longer quite the same arousing and threatening scent of testosterone in the air, though, no longer quite as strong a sense that Cruise is the lone dolphin in a school of sharks. This is a war movie for the Ted Lasso era, when, instead of idealizing the free market of male egos, audiences want to see people on screen being kinder to and more understanding of one another than almost anyone in real life has the emotional wherewithal to be. Among the young aviators in Maverick, only one has the full-fledged blond-beast frat-boy assholishness that prevailed when Cruise himself was a student. In real life, that archaic style has been exploded, and in a military context, even rendered nauseating by the war crimes of people like the Navy SEAL Edward Gallagher. I’m not saying it doesn’t exist any more; of course it does, and it’s still dangerous, but in the way of a cornered rat. Viewers know that if such a personality still tends to show up in elite military fighting units, it’s to some extent because it thinks it can take refuge there. And is safe not even there, really. One of the young aviators who makes the cut onto the final mission team is a woman, and another, perhaps even more tellingly, is a man whose call sign, “Bob,” is no more than his real name. The joke is that he isn’t even trying to be something other than ordinary. Maybe he’s gay? It would make a certain kind of metaphoric sense that in a post-closet world, the gay would be the one without an alter ego.

As for that disingenuousness: Ideology’s weapon, in the sequel, is nostalgia. The viewer is meant to sigh a little over the way technology is forcing pilots like Cruise and his young protégés into extinction. A colonel nicknamed the “Drone Reaper” is said to be shuttering the Navy’s dogfighter programs in order to pour more money into unmanned aerial vehicles, and the implication is that Cruise is a John Henry, who can’t help but keep trying to prove humanity’s superiority to machines, which is to say, to capital. “It’s not the plane, it’s the pilot,” is Cruise’s refrain in the movie, and his character totals half a dozen fighter jets, with as much abandon as if they were so many Ferris Bueller Ferraris. In reality, even though drones are replacing fighter jets, militaries today are more capital-intensive than ever, which, some economists theorize, is why America’s heavy military expenditure over the past quarter century failed to redistribute wealth the way that military expenditure during World War II did. Now more than ever, a nation may be understood as a population that can be taxed so reliably that you can take out a loan against the taxes; if you want to know who’s going to win a war, figure out which side has access to better (deeper, more continuous) financing.

Of all the reasons to feel bad about drones, the withering away of pilots may be one of the weakest. From the point of view of people being bombed on the ground, jets were never any more sporting than drones are. The nostalgia trip offered by Maverick is one last fight the old-fashioned way—a return to an ignorance that drone warfare has made more difficult. The nationality of the enemy that Cruise and his team are fighting is never named, and when the enemy pilots appear on screen, they’re hidden inside bug-like flight suits with opaque visors. In fact, thanks to drones, soldiers today often watch the people they have been asked to kill for so long that they begin to feel a kind of intimacy with them—and nonetheless still sometimes end up killing innocent civilians. And sometimes also end up becoming aware that they have done so. In a recent New York Times article about the moral injury that soldiers are now subject to, there’s a haunting story: An intelligence analyst working at an Air Force base is asked to take out a target in Afghanistan said to be a high-level Taliban financier. The analyst and his team track the man for a week, watching him tend his animals and eat with his family, and then a pilot on the team kills the man, remotely. A week later the man’s name appears on the target list again. They killed the wrong guy. This happened two more times, the analyst told the Times, before the analyst threatened to kill himself, was talked out of it, and was “medically retired.” In Top Gun: Maverick the fantasy is that it’s still possible to fly over these moral compromises at Mach 10 speed.

On Being Insulted by Literature

[An issue of my newsletter, Leaflet]

Should you keep reading a book if it insults the kind of person you are? In the old days the answer was: if it’s good, yes, you’re supposed to. Good as in of high literary quality. Nowadays, though, you’re free not to. You’ll still be considered a serious reader even if you put it down. It’s up to you.

A couple of months ago, I started to read Frederick Seidel’s Selected Poems, having liked poems of his that I had run into in magazines over the years, and having long heard him highly praised by friends. I thought I should see what the fuss was about. The persona of every Seidel poem was born into money, is passionate about riding Italian motorcycles, and is a libertine. Knowing this much about him had long put me off. I suspected he was going to be like James Merrill but straight and dickish—a suspicion that wasn’t entirely wrong. He writes lines like “I live a life of laziness and luxury,” and “I want to date-rape life.” A kind of provocativeness that trusts the reader to be in on the joke is part of his act. He’s sort of goofy, though, too, and his style is part Edward Lear (surrealist and singsongy), part Robert Lowell (crystallized and confessional), two poets I’m very fond of. Yes, Seidel brags about his Ducatis, his Huntsman suits, and his women, but he doesn’t come off as trying to make the reader envious. (Or maybe he is trying to make the reader envious and it doesn’t work on me because I don’t happen to covet any of those things? I’m going to try to stay open here to the possibility that my aesthetic reaction is a merely personal one, for reasons that will hopefully become clear.) He seems, rather, to be trying to synthesize and then bottle a sort of perfume, an attar of his pleasures, which is the kind of condensation of lived experience into language that I think of lyric poems as being for. Also, there’s something a little manic and fatal about his effort. There’s an undertone of desperation, a suggestion that his go-for-brokeness is somehow on account of having no choice, of having access to no other, more ordinary means of consolation. (And his poem, “The Blue-Eyed Doe,” about his mother’s lobotomy, is probably where one might start looking for the source of that desperation.)

In short, it turns out I quite like Seidel’s poems. But only a few pages into his Selected, reading a long poem titled “Sunrise,” I was stopped cold by these lines:

A gay couple drags a shivering fist-sized

Dog down Broadway, their parachute brake. “Why

Robert Frost?” the wife one pleads, nearly

In tears; the other sniffs, “Because he

Believed in Nature and I believe in Nature.”

The wife one. Okay. Well, what do I do with that?

It’s worth noting, before going any further, that a Black reader of Seidel will meet a similar challenge. Seidel is famous for having written bluntly, in poems such as “Bologna” and “Boys,” of the way his childhood self perceived the Black men who worked for his family. Indeed, in “Boys,” Seidel doubles down on the problem, and his narrator recalls one of those Black men as “probably a homo,” apostrophizing him thus: “Ronny Banks, faggot prince, where are you now?” There’s arguably a defense in the retrospective aspect of the poems about Black men: the poems are trying to recapture a perception that the poet had as a child, not a perception he necessarily still has today. Because the gay couple and their toy dog are perceived in the present tense, however, no such out is available.

Reader, I had feelings! My first, once I understood what Seidel meant by “the wife one,” was not very sophisticated: What a dick. On second thought, though, I remembered nights I had spent in gay bars in Manhattan, in my twenties, watching endlessly repeated video clips of two straight Black comedians, Damon Wayans and David Alan Grier, doing impressions of sissy film critics. I had had mixed feelings about the skits even at the time, but they were sometimes very funny, and they seemed to be taken to heart by almost everyone around me in the bars, perhaps because we gays back then felt a kind of hunger for representation in the mainstream, even for mocking representation. Maybe, in fact, a mocking representation was something we were especially hungry for, because mockery shone its spotlight on the elements of gay identity that were most stigmatized, elements that then seemed beyond the pale of a tolerant liberal understanding.

Seidel’s poem was written at least a decade before the “Men on Film” skits. Maybe he wrote the line having in mind a gay reader of an earlier era who would appreciate being sent up, in the way I remember appreciating “Men on Film”? That’s very possible. In his poem “Fucking,” Seidel recalls drinking at “Francis Bacon’s queer after-hours club” and being saluted by one of the regulars, who shouted, “‘Champagne for the Norm’! / Meaning normal, heterosexual.” That suggests a sort of interpellation across the border of stigma: You’re not one of us, but we recognize that you came to our turf. Hi, Norm! I’m convinced, perhaps irrationally, that there really was a gay couple who had an argument as they walked down Broadway with a small dog, and that Seidel noticed them, overheard them, and remembered them. I believe Seidel was paying attention, in other words, and attention is a gift. Mostly.

But but but. The phrase “the wife one” sounds to me like a straight man’s psychic shorthand, not like an attempt to borrow the voices that gay men use to talk about themselves, not even like an attempt to borrow in the parodic way of Wayans and Grier. I just don’t think a gay man would say “the wife one” except in jesting reference to the way the straight world sometimes perceives us. Not because it’s not respectful (gay men of my generation, left to our own devices, do not tend to treat ourselves qua gay with all that much respect), but because it’s not, by and large, the way gay couples work, in my experience. Sometimes it is the case that one partner in a couple is more effeminate than the other, but it seems to happen just as often, and probably more often, that both or neither are effeminate. The interaction and allocation of sex roles, gender roles, economic roles, and other social roles inside a gay relationship is just not as straightforward as a phrase like “the wife one” suggests (any more than the phrase accurately captures such matters inside a straight relationship, I suspect). A phrase like that simply isn’t useful. To cite just one complication: in his book Out of the Shadows, the psychotherapist Walt Odets notes that sometimes, for the sake of keeping a relationship in equilibrium, “a partner who holds the balance of power outside sex may be more sexually passive and receptive.”

So I don’t think this is a case of a straight writer borrowing a gay self-deprecation. I think what we have here is the appearance in a poem of a straight’s deprecation of gays. Which doesn’t mean there’s no ironic distance between Seidel the poet and Seidel the straight man (as it were)—between the Seidel who’s observing himself perceive and the Seidel who’s doing the perceiving. This is a defense that won’t convince some readers, but I think in a poet of Seidel’s sophistication, such an irony is always present, and I think it may be the strongest defense possible: this is who he was, and how he was, at the moment of this perception, and it’s impossible to capture perception fully while filtering it.

How badly is a defense needed? How terrible is it, really, to say “the wife one”? If you’re in a gay marriage, and you’ve never been asked by a straight man which of you is the wife, then you are luckier than me. I survived just fine, but I have to say I didn’t like it much. On the other hand, if you’re in a gay marriage, and you’ve never talked, fought, or joked, inside the safety of it, about which of you is behaving more as the wife, at a given stage of your relationship, then you are farther above the fray than I will ever be. In these jokes, arguments, and negotiations, though, I think what’s being hashed out is how to balance two careers, and how to divide the responsibilities for a shared household. The debates are about whether one person is feeling obliged to more often take the role of homemaker, not about whether one person is more womanly. (Gender isn’t a zero-sum game the way doing the dishes is, and at the end of the day, there isn’t, or shouldn’t be, anything offensive about describing a man as effeminate.) In other words, nothing is at stake that would be legible to someone who saw you and your husband walking down the street.

What were the gays in Seidel’s poem arguing about? Was “the husband one,” to coin a phrase, planning to ask for a Robert Frost poem to be read at his funeral? Was he planning to write a book or an article about Robert Frost? Was he merely claiming Frost as his favorite poet? In any of these cases, why would his partner “plead” for an explanation, “nearly in tears”? I think the reader is meant to find humor in the idea of a gay resident of New York City espousing Frost because of a shared belief in nature. Which I get. The canonical lines about gays and nature are Oscar Wilde complaining that “Nature is so uncomfortable. Grass is hard and lumpy and damp, and full of dreadful black insects,” and Frank O’Hara insisting that “I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.” But Peter and I had a friend read a Frost poem at our after-wedding get-together, and I defy even Jonathan Franzen to take better bird photos than I do.

I’m not sure I’ve walked in a wide enough circle around this problem yet. Did I feel insulted? Yes, a little, I guess. Do I care? I put Seidel’s Selected down for a while, but later I went back to it. I’m on my guard a little with Seidel now, but I should probably have learned long ago to be on my guard with every writer. I seem willing to forgive F. Scott Fitzgerald, say, for writing of a “pansy” character in Tender Is the Night that “he was so terrible that he was no longer terrible, only dehumanized.” Being dehumanized is worse, I think, than being called “the wife one.” I’m aware that I could pretend to care more than I do, in order to have an axe to swing. I sometimes wonder if, as a general public appreciation of literary qualities per se has weakened—as a willingness to make distinctions of literary value in public has declined—it has become more and more tempting to take up an axe. There are days when it seems like the only blades that still cut are those with a social or political edge. On the other hand, it would probably be a mistake to pretend I don’t care at all, to fake transcendence. A critic I didn’t agree with about much once warned me against accepting “the phantom bribe of straight culture,” and while I suspected him of issuing the warning in order to try to scare me off the middle ground that I wanted to occupy, I knew exactly what he meant. One aspires to catholicity as a reader—one wants to be broadminded even in the face of narrowmindedness—but one doesn’t want to be a pushover. I think my personal verdict would be to recommend that people read Seidel but not blink the moments like the one I’ve written about here, which are, after all, a deliberate part of his persona, and of the membership he claims through his poetry in a sort of freemasonry of the bad and wild (which more than a few gay men, of my generation anyway, have also felt they belonged to).

Surprise on board?

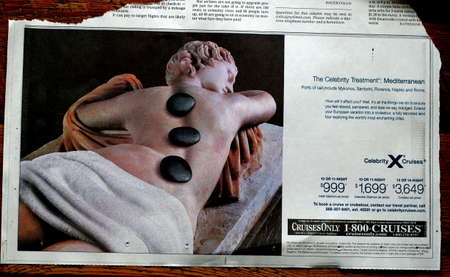

“How will it affect you?” this ad for Celebrity Cruises asks. It ran in the New York Times this past Sunday, and I tore it out because I thought the statue looked somewhat familiar. The delicate nose nestled against the right shoulder, the dimple over the left hip, the outward curl of the lower spine . . .

There are more than six known copies of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite in the world’s museums, according to the catalog of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome, which has one. (So does the Galleria Borghese, also in Rome, but the picture above is from the website of the Louvre, whose version has a sort of quilted mattress; the towel in the original, you will observe, is somewhat differently placed, and is not in fact terry-cloth.) Looking from the statue’s left, you see what appears to be the figure of a woman, but when you walk around to the other side, the story abruptly changes.

‘I’m glad we got that straight’

. . . says Tom Cruise to Kelly McGillis, just before he doesn’t make love to her. Last night Peter and I rented Top Gun, not for its topicality, which was mildly unnerving, but because we had put it on our Netflix queue ages ago. Neither of us saw it when it came out in 1986—in my case, because I was closeted and wary of the homo subtext that the movie was rumored to have. The homo subtext is indeed formidable (rather often a male hand trails rather loosely across another man’s shirtless back), but what struck me most was the crass instruction that the movie offered to insecure straight men. (In this it’s much like Jerry Maguire.)

The most salient feature of Maverick (Cruise) in Top Gun is how short he is. There’s scarcely a frame in which he isn’t the tiniest person, Charlie (McGillis) included. His fellow pilots tower over him, and his enormous smile looks not so much like generosity of spirit as the defensive gesture of someone cornered. He flashes it when attacked. The dilemma of being Maverick is this: if you are short, have no father, lack impulse control, and cannot sing, how will you ever get laid? The answer is that you will turn two of your vulnerabilities into strengths: low impulse control will become a willingness to take risks that others won’t. This transformation is easy for Maverick, and he’s a little too fond of it. But the second is trickier: His wish for a father is to become an ability to bond tightly to his comrades. Herein lies the lesson, and it is unlovely. Maverick’s bonding is too personal; it’s really only to Goose, his “rear man,” whom the filmmakers have made ugly, to deflect suspicion. Maverick must eliminate the component of his love that is attached to a particular beloved. He must learn not to care when Goose dies.

Thus the emotional nonsense of the movie’s opening scene, when a pilot named Cougar freaks out, during a dogfight, and can’t pull himself together to land his plane but merely stares fixedly at a photo of his wife and children. I say nonsense, because presumably the thought of his wife and children would be an incentive to Cougar to rejoin the living. But instead the thought of them seems to tempt him to die at sea. That’s because the scene has no coherence of its own but is merely a setup to Maverick’s decision, in a later dogfight, not to die at sea as Goose did—not to “follow his leader,” as Melville might have put it.

If Tom can do this—and “this” is not mourning, it’s something quicker and more brutal, like cauterization—then he can have Charlie (McGillis). Note that for as long as it seems that he can’t do this, she rejects him, with a heartlessness that would be a flashing red alarm if a real woman were to display it. But she isn’t a real woman, she is the goddess of reproductive success, available to all who can accurately simulate alpha-male status. Maverick isn’t really an alpha male (note his prompt decision to become a professor once his warrior bona fides are proven), which is why the audience roots for him in his struggle to appear to be one.