The Onion this week reprints its issue of 6 October 1783, including such articles as “Thousands More Teeth Lost,” “Rural Quaker Scandalized by Intricate Furniture Pattern,” “Citizens Now Free to Practise Any Form of Protestantism They Want,” and “Mule-Deaths of Late.” If, like me, you are the sort who laughs at such things as the Donald Barthelme story “An Hesitation on the Bank of the Delaware,” in which a soldier warns George Washington, “But, General, unless we launch the boats pretty shortly, the attack will lose the element of furprife,” you will probably appreciate the humor.

Category: American history

Notebook: “There She Blew”

“There She Blew,” my review of Eric Jay Dolin’s Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America, is in the 23 July 2007 issue of The New Yorker. Herewith a few web extras and informal footnotes.

As ever, my first thanks go to the book under review. I also consulted the conservationist and historian Richard Ellis’s Men and Whales (Knopf, 1991), which takes the story of whaling beyond America, and the economists Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter’s In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 (University of Chicago, 1997), which contains empirical data and insights that will interest Ph.D.’s as well as M.B.A.’s. The best documentation of Melville’s life as a whaler is in Herman Melville’s Whaling Years (Vanderbilt, 2004), a 1952 dissertation revised by its author, Wilson Heflin, until his death in 1985, and astutely edited for publication by Mary K. Bercaw Edwards and Thomas Farel Heffernan. (It’s from a note in Heflin’s book that I found the description of sperm-squeezing in William M. Davis’s 1874 memoir.) Two nineteenth-century memoirs of whaling that I refer to—J. Ross Browne’s Etchings of a Whaling Cruise and Francis Allyn Olmsted’s Incidents of a Whaling Voyage—are available online thanks to Tom Tyler of Denver, Colorado, as part of his edition of journals kept aboard the Nantucket whaler Plough Boy between 1827 and 1834. William Scoresby Jr.’s Account of the Arctic Regions, with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery is available in Google Books. (For the record, though, I read on paper, not online. I’m not really capable of reading books online.)

Also very useful was Briton Cooper Busch’s “Whaling Will Never Do for Me”: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1994), which told me about bored shipboard wives and the whaler who read Moby-Dick while at sea, and Pamela A. Miller’s And the Whale Is Ours: Creative Writing of American Whalemen (Godine, 1971), my source for the quatrain about sperm whales vanishing from “Japan Ground.”

Now for the wildly miscellaneous. While I was researching the review, some Eskimos killed a bowhead whale off the shores of Alaska and found in its blubber the unexploded explosive tip of a bomb lance manufactured in the 1880s; the discovery got a short paragraph in the New York Times (“This Whale’s Life . . . It Was a Long One”), and a longer explanation on the website of the New Bedford Whaling Museum (“125-year-old New Bedford Bomb Fragment Found Embedded in Alaskan Bowhead Whale”). The NBWM has some great photographs of whaling in its online archives, from an inadvertently campy tableau of a librarian showing a young sailor how to handle his harpoon in the 1950s (item 2000.100.1449), to a sublime and otherworldly image of a backlit “blanket piece” of blubber being hauled on board a whaler in 1904 (item 1974.3.1.93). The blanket piece was photographed by the whaling artist Clifford W. Ashley, as part of his research for his paintings; he also took pictures of a lookout high in a mast (item 1974.3.1.221), a sperm whale lying fin out beside a whaler (item 1974.3.1.73), the “cutting in” of a whale beside a ship (item 1974.3.1.34), and whalers giving each other haircuts (item 1974.3.1.29). Though taken in 1904, they’re the best photos of nineteenth-century-style whaling I’ve seen, and they’re also available in a book, Elton W. Hall’s Sperm Whaling from New Bedford, through the museum’s store.

The best moving images of whaling are in Elmer Clifton’s 1922 silent movie “Down to the Sea in Ships,” which features Clara Bow as a stowaway in drag and has an absurd plot, complete with a villain who is secretly Asian. It stars Marguerite Courtot and Raymond McKee (who was said to have thrown the harpoon himself during the filming), as well as real New Bedfordites and their ships, as Dolin explains, and even has a scene of Quakers sitting wordlessly in meeting, the purity of which tickled me. It has been released by Kino Video on DVD and is available via Netflix as part of a double feature with Parisian Love. The NBWM has a great many stills; try searching for “Clifton” as a keyword.

If photographs strike you as too anachronistic, you can find the occasional watercolor whaling scene in the nineteenth-century logbooks digitized by the G. W. Blunt White Library of the Mystic Seaport Museum, such as these images from the 1841-42 logbook of the Charles W. Morgan (MVHS Log 52, pages 37 and 43). There is more scrimshaw than you will know what to do with at the Nantucket Historical Association. If you want to hear whales, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has at least two websites with samples, and there are more here, courtesy of the University of Rhode Island.

The conceptual, book-based artist Alex Itin has an intriguing video collage of Moby-Dick the text and Orson Welles the actor; Welles tried a number of times to stage a version of the novel. And much further down the brow of culture, the Disney corporation did an animated book review of Moby-Dick a few years ago. (I can’t promise it won’t work your last nerve.) Last but not least, here are NOAA’s estimates of current whale populations, by species, and the homepage of the International Whaling Commission, responsible for the animals’ welfare.

Photo credit: Harry V. Givens, photographer, “Whale Skeleton, Point Lobos, California,” American Environmental Photographs Collection (1891-1936), AEP-CAS206, Department of Special Collections, University of Chicago Library (accessed through the Library of Congress’s American Memory website).

Notebook: Aimee Semple McPherson

“The Miracle Woman,” my review of Matthew Avery Sutton’s biography Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America appears in the 19 July 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books. (It’s not available for free online. Please subscribe! Otherwise someday there will be no more steamboats…) What follows is supplemental, and not likely to make sense until you read the article.

As ever, my first thanks are owed to the book under review. A couple of other sources made it into the article’s footnotes: Edith L. Blumhofer’s Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody’s Sister (Eerdmans, 1993) and Daniel Mark Epstein’s Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson (Harcourt, 1993). Since I didn’t have room in my article to give much sense of these books as books, it may be worth saying here that their styles are quite different: prose-poetical and trusting in Epstein’s case, authoritative and reserved in Blumhofer’s. Sutton praises both of them in his book, and writes that he hurried past McPherson’s youth because they covered it so well, choosing instead to focus on her later years, which they scanted. That’s true of Blumhofer, whose tact constrains her to a cryptic brevity when she reaches the bickering and scandal of McPherson’s last decade. Epstein, though, provides a few more of the late twists and turns than Sutton does, and may in the end give the most complete picture. (Unfortunately, he’s not always perfectly accurate. For example, he writes that McPherson failed to attend her father’s funeral in 1927, but he is contradicted by the obituary he quotes, which states that her father died at eighty-five, his age in 1921. Indeed, Blumhofer reports that McPherson’s father died in 1921, and has evidence, furthermore, that Aimee did return to her hometown for the service.) The other important biography of McPherson is Lately Thomas’s Storming Heaven: The Lives and Turmoils of Minnie Kennedy and Aimee Semple McPherson (Morrow, 1970), which traces McPherson’s path through the pages of American newspapers in great detail; on the subject of McPherson, Thomas notes, the “press record is almost inexhaustible.” The result is somewhat unfiltered and “bitty,” as the English say, but the newspaper photographs that illustrate the book alone make it worthwhile.

In 1999, a University of Virginia undergraduate named Anna Robertson put together a slide show of McPherson photographs, an Aimee Semple McPherson cut-out doll published by Vanity Fair in the 1920s, and a number of other images and documents. There are also pictures on the website for “Sister Aimee,” a PBS documentary that drew on Sutton’s book, and on a webpage about McPherson managed by the Foursqure Church, the Pentecostal denomination she founded.

In his novel Elmer Gantry, Sinclair Lewis modeled the character of Sharon Falconer on McPherson. He described Falconer’s voice as “warm, a little husky, desperately alive,” and that matches McPherson’s, which you can hear preaching about Prohibition at the History Matters website. You can also hear early recordings of McPherson in a 1999 radio program, “Aimee Semple McPherson — An Oral Mystery,” part of NPR’s Lost and Found Sound series.

An odd side note, which I never even tried to sandwich into my article: Blumhofer writes that after Aimee and her second husband, Harold, separated in 1918, Harold preached for a while with “John and Elizabeth Ashcroft, evangelists in Maryland, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania.” From scanning a few online biographies and genealogies, I’m fairly sure that these were the grandparents of former attorney general John Ashcroft.

Oh, and the photo above. Aimee Semple McPherson appears as a character in Upton Sinclair’s 1926 novel Oil!, but Sinclair switched McPherson’s sex when he novelized her. Like McPherson, Eli Watkins is a preacher in the Pentecostalist tradition who vanishes and is thought to have drowned; he comes back with a tale of having been held up in the water by three angels, though the rumor is that he spent the missing days in a beachfront hotel with an attractive young woman. That isn’t Eli Watkins on the book’s cover, which is the Grosset & Dunllap edition, because Watkins’s story is really no more than a minor subplot. The novel mostly concerns an idealistic young man, Bunny Ross, who discovers as he grows up that the oil business, which his father works in, corrupts politicians and civic life generally. Eventually Bunny becomes a “millionaire red,” vowing to spend his inheritance on a socialist labor college. When Bunny hears Eli preaching on the radio what he knows to be lies, he thinks to himself,

The radio is a one-sided institution; you can listen, but you cannot answer back. In that lies its enormouss usefulness to the capitalist system. The householder sits at home and takes what is handed to him, like an infant being fed through a tube. It is a basis upon which to build the greatest slave empire in history.

The woman in the illustration may be Eli’s sister, Ruth, a sort of shy shepherdess, who never quite turns into the love interest.

Pattern in Material Book Culture

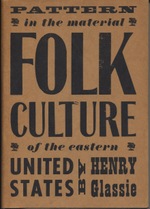

I’ve threatened, at various times, to say unkind words about book design. But I realized recently that it would be better for my karma to say a few kind ones. In fact, there’s a lot of book design that I like, and it isn’t easy to choose which book to praise. It occurred to me that the purest selection would be of a book I haven’t actually read, so that any fondness I might have for content would be neutralized. And I haven’t actually read (not every page, anyway) Henry Glassie’s Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), which, according to the back flap of the dust jacket, was designed by someone named Bud Jacobs.

I’ve threatened, at various times, to say unkind words about book design. But I realized recently that it would be better for my karma to say a few kind ones. In fact, there’s a lot of book design that I like, and it isn’t easy to choose which book to praise. It occurred to me that the purest selection would be of a book I haven’t actually read, so that any fondness I might have for content would be neutralized. And I haven’t actually read (not every page, anyway) Henry Glassie’s Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), which, according to the back flap of the dust jacket, was designed by someone named Bud Jacobs.

As a rule I’m not wild about typographic covers, but I like this one, because the wood-block lettering nods to the book’s theme of handmade culture and to its time period. You know at once that this is a book about America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and that it’s a little nostalgic, but not fussily so. This is going to be a kind of playful remix. The size of the words corresponds to their importance: in descending order, Folk, Culture, United States, and Pattern. Also, no computer went near this cover. Every letter on it was manifestly kerned by eye and hand.

The page design for Pattern is a scholarly kind of beautiful. It geeks out, and it makes geeking out look lovely. The footnotes are at the feet of the pages, for one thing—not banished to the book’s end. This is important, because the notes are designed, as the author explains in his “Apology and Acknowledgment,” to “provide a loose bibliographical essay.” They’re a kind of anchor to the book’s text, which the author describes as an “impressionistic introduction.” The text meanders, while the footnotes march on, beneath, in an orderly regiment.

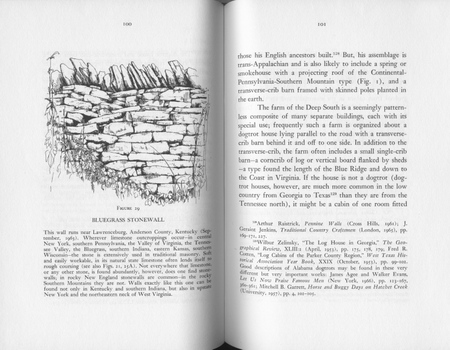

As a third design component, the book has many illustrations, one on nearly every other page, each of which comes with a leisurely caption, which in some cases amounts to a free-standing essay. In the layout above, for example, the caption discusses variations in stone walls, from New England to Kentucky, while the text focuses on the dogtrot house typical of farms in the Deep South, and a footnote directs the reader to descriptions of Alabama dogtrots in Evans and Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, among other sources.

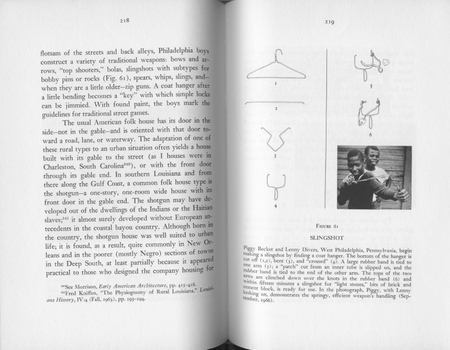

Glassie’s book isn’t merely bibliography and synthesis, however. Some of the information comes from his own field work. He presents a photograph of a rabbit gum, a wooden box trap to catch rabbits. And he prints an interview with a man who used to “sting” fish as a boy; when he saw a fish swimming just under the ice of a creek, he would hit the ice with a mallet to stun the fish beneath, and then cut the ice and take the stunned fish out. An illustration displays the man’s sketch, from memory, of his fish stinging mallet, and a footnote assures the reader that “stinging fish is not a tall tale” by pointing to a similar recollection in print elsewhere. But I’m becoming distracted from pure design, so here’s another layout, which mixes line drawings, a photograph, and a caption to show you how to make a slingshot out of a coathanger, West Philadelphia-style.

There’s an index of fearful completeness, of everything from bacon-grease salad dressing to lobster pots. And one more clever touch worth mentioning, the book’s spine:

It’s a little hard to read, because the technology was no longer really up to spec for machine-made books in 1968, but Bud Jacobs seems to have tried to gild the book’s spine in the style of American books of the mid-nineteenth century. Jacobs stamped the spine with an indicator hand, the book’s title, and the press’s insignia. Back in the day, gilded spines were even more elaborate, in many cases, and the gilding was applied by hand. To the right are a few samples from the 1840s and 1850s, featuring a philanthropess, a waif, and a den of iniquity; a conductor; floral bouquets; the scales of justice; and an all-seeing eye.

Notebook: Jackson and habeas corpus

"Bad Precedent," my essay on Andrew Jackson and habeas corpus, appears in The New Yorker on 29 January 2007. As with earlier articles, I'm posting here a few outtakes and tips of the hat.

As ever, I owe the most to the book under review, Matthew Warshauer's Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law: Nationalism, Civil Liberties, and Partisanship (available from Amazon and, for the same price, directly from the University of Tennessee Press).

I also learned much from three recent biographies of Jackson, very different in style and perspective. Jackson provokes feelings of surprising intensity, considering that he's a long-dead historical figure, and a great virtue of H. W. Brands's Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times is that it explains the sturm and drang around him in a calm, careful tone. Brands relies for the most part on published sources and doesn't offer new archival discoveries, but he places Jackson in context with impressive clarity, and his narrative is well constructed. (My only quibble is with his reliance, in a few places, on anecdotes about Jackson's early life from an early-twentieth-century account by Augustus C. Buell; Buell's stories were probably fiction, the scholar Milton W. Hamilton asserted in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography in 1956. Of course it's possible that Brands has found reason to dissent from Hamilton's athetization. . . .)

Brands offers a generous but highly readable 600-plus pages. Sean Wilentz's Andrew Jackson, by contrast, is as lean and sinewy as Jackson himself. It also shares with Jackson an appetite for controversy: at 195 pages, Wilentz's book is designed for the reader who wants an introduction to Jackson in the course of an afternoon, but Wilentz manages nonetheless to find room to mount a sophisticated defense of Jackson from attacks by other historians—attacks which, he argues, fail to take account of the political realities of Jackson's day. Among others, Wilentz critiques Andrew Burstein, who, in The Passions of Andrew Jackson, condemns Jackson harshly, as a person and as a leader. Burstein's isn't a straight biography, but rather a study from a perspective that's a little hard to describe—a mixture of social history, psychology, and cultural studies. Burstein scants the political context, which is a rather large piece of the puzzle to leave out. Still, Burstein seems to have immersed himself in the primary sources, and presents evidence, often highly colorful, that is not easy to find elsewhere.

The big books on Jackson are two three-volume biographies: James Parton's, issued in 1859 and 1860, and Robert Remini's, issued in 1977, 1981, and 1984. Parton seems to have had most of the important sources available to him, and he's a beautiful stylist. Here he is setting the scene of New Orleans: "The Mississippi is apparently the most irresolute of rivers; the bed upon which it lies cannot long hold it in its soft embrace." And here he is on the impossibility of recovering the truth about Jackson's duel with legislator Thomas Hart Benton:

Neither the eyes nor the memory of one of these fiery spirits can be trusted. Long ago, in the early days of these inquiries, I ceased to believe any thing they may have uttered, when their pride or their passions were interested; unless their story was supported by other evidence or by strong probability. It is the nature of such men to forget what they wish had never occurred; to remember vividly the occurrences which flatter their ruling passion; and unconsciously to magnify their own part in the events of the past.

All three volumes of Parton's biography of Jackson are in Google Books: volume 1, volume 2, and volume 3. (The image above is the frontispiece to volume 2.) Though Parton sees Jackson's merits, he is not a fan, as Remini sometimes is. Remini is a researcher of great energy and diligence, and I would guess that he's the only person who has discovered more about Jackson than Parton did. I found myself disagreeing with some of his analyses, however. For example, Remini argues that Jackson's New Orleans victory did affect the territorial outcome of the War of 1812, despite the prior signing of the Treaty of Ghent. That seems unlikely to me, on the face of it; moreover, in 1979, in the journal Diplomatic History, the scholar James A. Carr turned to British military correspondence and internal diplomatic memoranda to show that by the end of the War of 1812, the British wanted nothing more than to wash their hands of America and conflict with Americans.

The article by Abraham D. Sofaer that I refer to at the end of the article is "Emergency Power and the Hero of New Orleans," Cardozo Law Review 2 (1980): 233 ff. Also useful, as I was thinking through the legal issues, was Ingrid Brunk Wuerth's "The President's Right to Detain 'Enemy Combatants': Modern Lessons from Mr. Madison's Forgotten War," Northwestern University Law Review 98 (2004):1567 ff. Unfortunately, neither of these is available online for free, though they're easy to find in for-profit databases. In fact, I turned up remarkably few Internet-enhanced multimedia supplemental whirligigs during my tours of Web procrastination this time out, but no Andrew Jackson blog post would be complete without a reference to the large White House cheese, and someone has digitized all of Benson J. Lossing's Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812, which has some of the best battle diagrams going, if you plan to read a blow-by-blow account and want some visual guidance. Of course, the Hamdan v. Rumsfeld decision is online, as is the Military Commissions Act of 2006, and they may be profitably read side by side.