“To see a painting or a statue, he thought, and then to look out of the window, is to see how fresh and richer life itself is. He had read this a few weeks before in the volume of a German philosopher, and because Ezekiel had always felt so, the sentence had significance.” —Charles Reznikoff, By the Waters of Manhattan

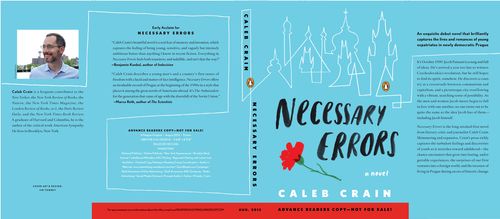

Does anyone know which German philosopher Reznikoff’s hero was reading? I had the impression that the idea in question was originated by Muriel Spark, but Reznikoff’s novel was published in 1930, so this can’t be Spark in German drag. I bought (from Better Read than Dead) and read By the Waters of Manhattan because, shallow person that I am, I thought the cover of the paperback, by Amy Drevenstedt, was gorgeous, and as usual, my superficiality was rewarded. It’s a solid page-turner. The first two-thirds is about a Jewish woman growing up in eastern Europe in a family full of idealistic and often hapless men. The second is about her son starting a bookstore on the Lower East Side and venturing into a somewhat amoral romance with one of his customers.

“Haven’t smoked for three days. Busy night and day not smoking. Already I can climb stairs better but that’s not much of a life. With smoking one has a life while dying. How did the Greeks ever run a whole culture without it? Maybe that’s why there was so much homosexuality.” —Russell Hoban, Turtle Diary

“Car horns serve the same purpose as birdsong—to warn away rivals, or to express annoyance.” —Sparrow, The Princeton Diary

This isn’t quite the case, of course, or anyway not exclusively—birds also use song for courtship, spooking prey, begging, and staying findable to mates and colleagues—but I lolled. I wrote a post about Sparrow’s previous novel, Abraham, a couple of years ago, and so far the new one is also very quotable (“Princeton is what New Jersey would be like without the mafia.”)

Years ago, soon after I landed my first real job, as a senior (sc. junior) editor at Lingua Franca, I bought a set of the old Houghton Mifflin / Riverside Press edition of Thoreau’s journals, which happened to have belonged to the late critic Alfred Kazin. I had read “in” Thoreau’s journals a fair amount in grad school, and I read “in” them some more when I did a Thoreau-related review soon after buying the set, but it was only last year that I sat down with the intention of reading them through. Having started birdwatching myself makes it more plausible, somehow. Sometimes I cross-check with the new Princeton edition, which I have many but not all volumes of, but I seem to prefer the old Riverside Press edition for actual reading, just as I seem to prefer the more-edited editions of John Clare. It turns out I’m not a purist and appreciate punctuation. Adding to the pleasure of the copy of Thoreau’s journal that I have are Kazin’s copious pencil annotations. I particularly liked this one, of Thoreau’s entry for October 14, 1851:

“She had no ambition to write a good book, but was painfully anxious to write a book that critics should say was good.” —Trollope, The Way We Live Now