“The Miracle Woman,” my review of Matthew Avery Sutton’s biography Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America appears in the 19 July 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books. (It’s not available for free online. Please subscribe! Otherwise someday there will be no more steamboats…) What follows is supplemental, and not likely to make sense until you read the article.

As ever, my first thanks are owed to the book under review. A couple of other sources made it into the article’s footnotes: Edith L. Blumhofer’s Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody’s Sister (Eerdmans, 1993) and Daniel Mark Epstein’s Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson (Harcourt, 1993). Since I didn’t have room in my article to give much sense of these books as books, it may be worth saying here that their styles are quite different: prose-poetical and trusting in Epstein’s case, authoritative and reserved in Blumhofer’s. Sutton praises both of them in his book, and writes that he hurried past McPherson’s youth because they covered it so well, choosing instead to focus on her later years, which they scanted. That’s true of Blumhofer, whose tact constrains her to a cryptic brevity when she reaches the bickering and scandal of McPherson’s last decade. Epstein, though, provides a few more of the late twists and turns than Sutton does, and may in the end give the most complete picture. (Unfortunately, he’s not always perfectly accurate. For example, he writes that McPherson failed to attend her father’s funeral in 1927, but he is contradicted by the obituary he quotes, which states that her father died at eighty-five, his age in 1921. Indeed, Blumhofer reports that McPherson’s father died in 1921, and has evidence, furthermore, that Aimee did return to her hometown for the service.) The other important biography of McPherson is Lately Thomas’s Storming Heaven: The Lives and Turmoils of Minnie Kennedy and Aimee Semple McPherson (Morrow, 1970), which traces McPherson’s path through the pages of American newspapers in great detail; on the subject of McPherson, Thomas notes, the “press record is almost inexhaustible.” The result is somewhat unfiltered and “bitty,” as the English say, but the newspaper photographs that illustrate the book alone make it worthwhile.

In 1999, a University of Virginia undergraduate named Anna Robertson put together a slide show of McPherson photographs, an Aimee Semple McPherson cut-out doll published by Vanity Fair in the 1920s, and a number of other images and documents. There are also pictures on the website for “Sister Aimee,” a PBS documentary that drew on Sutton’s book, and on a webpage about McPherson managed by the Foursqure Church, the Pentecostal denomination she founded.

In his novel Elmer Gantry, Sinclair Lewis modeled the character of Sharon Falconer on McPherson. He described Falconer’s voice as “warm, a little husky, desperately alive,” and that matches McPherson’s, which you can hear preaching about Prohibition at the History Matters website. You can also hear early recordings of McPherson in a 1999 radio program, “Aimee Semple McPherson — An Oral Mystery,” part of NPR’s Lost and Found Sound series.

An odd side note, which I never even tried to sandwich into my article: Blumhofer writes that after Aimee and her second husband, Harold, separated in 1918, Harold preached for a while with “John and Elizabeth Ashcroft, evangelists in Maryland, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania.” From scanning a few online biographies and genealogies, I’m fairly sure that these were the grandparents of former attorney general John Ashcroft.

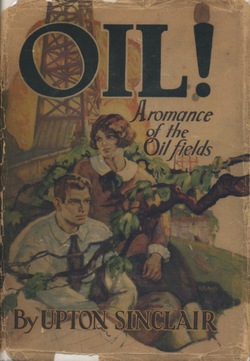

Oh, and the photo above. Aimee Semple McPherson appears as a character in Upton Sinclair’s 1926 novel Oil!, but Sinclair switched McPherson’s sex when he novelized her. Like McPherson, Eli Watkins is a preacher in the Pentecostalist tradition who vanishes and is thought to have drowned; he comes back with a tale of having been held up in the water by three angels, though the rumor is that he spent the missing days in a beachfront hotel with an attractive young woman. That isn’t Eli Watkins on the book’s cover, which is the Grosset & Dunllap edition, because Watkins’s story is really no more than a minor subplot. The novel mostly concerns an idealistic young man, Bunny Ross, who discovers as he grows up that the oil business, which his father works in, corrupts politicians and civic life generally. Eventually Bunny becomes a “millionaire red,” vowing to spend his inheritance on a socialist labor college. When Bunny hears Eli preaching on the radio what he knows to be lies, he thinks to himself,

The radio is a one-sided institution; you can listen, but you cannot answer back. In that lies its enormouss usefulness to the capitalist system. The householder sits at home and takes what is handed to him, like an infant being fed through a tube. It is a basis upon which to build the greatest slave empire in history.

The woman in the illustration may be Eli’s sister, Ruth, a sort of shy shepherdess, who never quite turns into the love interest.