On 19 December 2012, at 11am, the New York Public Library presented in outline the architectural plans for its Central Library Plan (CLP), a proposal to close the Mid-Manhattan Library and the Science, Industry, and Business Library and replace the bookshelves that house the 42nd Street building’s research collection with a new circulating library. The library’s president Anthony Marx and its chosen architect Norman Foster spoke. In the weeks since this press conference, architecture critics have begun to weigh in—some positive, some negative. I took notes, and though I’ve already written up my first impression, Marx and Foster released a number of details that don’t seem to have made it into press accounts, and I thought I would share my notes here. (When I can’t resist editorializing, I’ll set off my comments with parentheses and italics, like this.)

“Our aim,” said Marx, in his remarks at the press conference, “is to provide to New Yorkers and to all comers the greatest library facility in the world.” The CLP, he said, aspires to “bring back to this building the two halves of this great library”—its circulating and its research missions. He described the new space, which is to be inserted in the space under the Rose reading room, where the bookshelves of the research library now stand, as “a brand-new state-of-the-art Mid-Manhattan Library and Science, Industry and Business Library,” adding that because the future of all libraries, including the New York Public, remains unclear, the new space will be flexible.

Marx insisted that the 42nd Street building would continue to be a “great space for exhibitions.” He said that the building’s research collection was “currently housed in stacks with almost no climate control or fire safety” and that under the new dispensation, the books would be much better cared for—in fact, five times better cared for. (Though he didn’t name it, Marx seems here to have been referring to the 42nd Street building’s rating on the Time-Weighted Preservation Index, a measurement scale devised by the Image Permanence Institute. As I explained in an earlier blog post, the 42nd Street stacks are currently rated 44.5, which means that a book held there suffers as much damage in 44.5 years as a book stored at 68 degrees Fahrenheit and 45 percent relative humidity would suffer in 50 years. Under the CLP, by comparison, books would be stored in conditions where it would take 163 to 244 years for them to suffer an equivalent amount of damage.) The books will get what they need, Marx said, and the people, what they need. Marx claimed that the administration expects the CLP to make available to the library an additional $15 million a year. (There’s a touch of spin here: The library’s chief operations officer has estimated that the savings from consolidating three buildings into one would amount to only $7 million a year. The difference between $7 million and $15 million is to come from interest that would accrue on new funds raised for the CLP.) Marx promised that the renovated building would stay open until 11pm most nights, “revitalizing the evening experience in this neighborhood.”

Marx acknowledged that the CLP had come in for criticism, and he asserted that “we heard concerns about the plans,… and we adjusted and improved them.” He said that no public spaces in the building were going to change. In fact, he said, spaces not previously open to the public were going to be made newly accessible. In closing, he remarked that in the days just after Hurricane Sandy, visits to the “aesthetically challenged” Mid-Manhattan Library had doubled, and as proof of the library administration’s commitment to serving the public, he pointed out that despite recent, unexpected budget cuts, the library hasn’t closed branches or cut hours.

The architect Norman Foster then presented a slideshow, which surveyed the changes to the 42nd Street building over time and his proposed alterations to the structure. Foster began by noting that the Rose reading room is 51 feet high and that a visitor has to climb 50 feet through the 42nd Street building in order to reach it. Returning to this symmetry, somewhat later in his remarks, Foster observed that the volume that contains the bookshelves under the Rose reading room is roughly the same size as the volume of the Rose reading room itself. Foster pointed out that there had been a circulating library inside the 42nd Street building once before, in the space now known as the Bartos Forum, and that there had previously been a children’s library in rooms on the ground floor currently used for administrative offices. At the moment, Foster said, 30 percent of the building is open to the public; the CLP would make 66 percent of the building publicly accessible. (It seems worth pointing out that the proportion of the 42nd Street building open to the public may not be the most pertinent statistic. The CLP calls for the closing of two other facilities: the Mid-Manhattan Library and the Science, Industry, and Business Library. I suspect that the total amount of floorspace open to the public will remain little changed. Also, it would be possible to open new writer’s spaces on the second floor of the 42nd Street building and a new children’s library on the ground floor without removing the building’s bookshelves.)

Foster noted that in the 1980s, a space for an underground parking lot had been excavated beneath Bryant Park, next-door to the library, and after the city intervened, one of two levels in this space was devoted to book storage instead of parking. The second level was left empty for years, but thanks to a gift from Abby and Howard Milstein announced in September, soon this second level, too, will be able to hold books. (This is a significant alteration to the CLP, and a major concession to critics like me who were concerned that the CLP would drastically reduce on-site book storage. I, for one, appreciate it greatly.) Thanks to the Milsteins’ gift, the capacity of the Bryant Park Stack Extension will grow from 1.5 million to 3 million volumes. The above-ground stacks in the 42nd Street building, meanwhile, hold 3 million books. In an animated diagram, Foster showed the books that used to be stored in the 42nd Street building flowing into the new facility under Bryant Park. (Foster was indulging in a little sleight of hand here. The 3 million books once stored in the 42nd Street stacks will indeed fit in the new Bryant Park storage facility—but only if the 1.5 million books that were formerly stored under Bryant Park are sent away to off-site storage in New Jersey. This is an improvement over the original plan—which was to send 3 million books to New Jersey and keep only 1.5 million under Bryant Park—and as I said, I appreciate the improvement greatly, but it remains true that the CLP will entail a loss of on-site storage.)

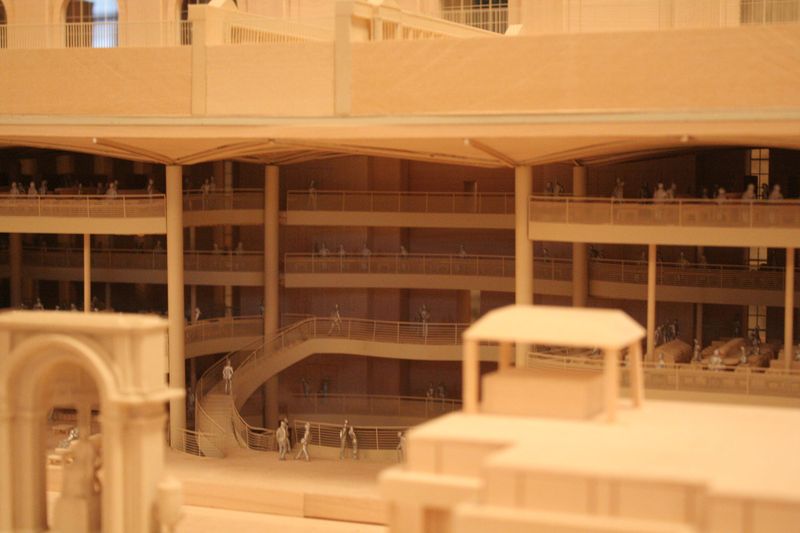

Foster then showed images, including a video “fly-through,” of the construction he proposes for the space under the Rose reading room currently occupied by bookshelves. In Foster’s fly-through, visible here, a viewer enters the building from Fifth Avenue, crosses the vestibule known as Astor Hall, walks through the exhibition space known as Gottesman Hall, and emerges on the third of five floors (or the second of four, depending on whether you count the lowest level) that Foster would like to insert into the space under the Rose reading room. These four (or five) levels looked to me a bit like loggias in an opera house. They’re hollowed out in the center, as if around an orchestra pit. The proscenium that they face is the western façade of the library, which looks out onto Bryant Park.

Foster acknowledged that the Rose reading room is currently supported structurally by the cast-iron “stacks,” or bookshelves, under it. He said that the engineers who would handle the removal of the stacks are those responsible for the recent creation of new spaces under Carnegie Hall and under City Hall, and that he was confident that they were up to the challenge. (Marx later identified the firm as Robert Silman Associates, and indeed they seem to have an excellent reputation.) Foster said that the delivery desk in the Rose reading room, the central point for receiving and distributing books, would remain unchanged. He said that it was still “early days” in terms of design choices, but that he expected the new space would be furnished in wood, bronze, and stone, materials “which age gracefully” and are used elsewhere in the building. He said that he hoped to recycle some of the existing book stacks as shelving in the new space. He asserted that the new space would be 65 feet high, and that as he planned for the ceiling, he was struck by the frosted-glass skylights elsewhere in the 42nd Street building—a hint that he was considering installing an artificially lit frosted-glass skylight.

During the question-and-answer period, Scott Sherman of The Nation asked Foster if he had any misgivings about the CLP in light of Ada Louise Huxtable’s recent strong critique in the Wall Street Journal. “No,” Foster replied. “The history of the building is one of change over time. The world today is not what it was in 1911,” when the 42nd Street structure was built. “I respect your question,” Foster continued; “I disagree with you.”

Someone else asked about the structural hazard that the demolition of the stacks posed to the Rose reading room, and Foster replied by shifting the question to a different danger: “The Rose reading room is currently at risk,” he said. “It’s the only public space in New York that sits on an un-fire-protected space…. If part of the story [of the renovation] is protecting the books, then another part is that we’re also protecting the Rose reading room. I cannot speak for the engineers, but they’re some of the best in the world.” In response to a second question about the logistics of renovating without endangering the Rose, Foster explained that in an initial phase, the engineers would create structural elements between the stacks that would hold up the Rose. Then, once this new supporting structure was in place, the engineers would remove the stacks. Foster said that he expected the new facility to open in 2018, and Marx promised that the 42nd Street building would stay open during construction.

I raised my hand and asked how books would reach the Rose reading room from the Bryant Park storage facility, since the plans suggested that the elevator that formerly raised books to the Rose delivery desk would soon be no more. I gave an account of the exchange in an earlier post, and to save time, I’ll repeat it here:

There’s currently a conveyor belt that brings books from the Bryant Park Stack Extension into the library building, and in reply to my question, Marx said that a second conveyor belt would be added to it, and a new elevator built somewhere on the south end of the building. The architectural historian Charles Warren followed up my question with a few others: Would the new elevator be put where the Art and Architecture reading room is now located? No, it was to be to one side, probably in the southeast corner of the Rose room. How would books get from the southeast corner of the Rose to the delivery desk? There might be room to build yet another conveyor belt in the crawl space between the floor of the Rose Reading Room and the drop ceiling of the new circulating library. Was this crawl space large enough for a person to walk in it? No. Then how would the conveyor be repaired if it broke?

Marx and Foster assured Warren that they would be able to come up with an answer.

Another questioner asked about the project’s funding, and Marx answered that the CLP was “self-funded.” He repeated the claim that the CLP will improve the library’s bottom line by $15 million a year, but he also said that financial gain was “not the driver of this project.” (The finances behind the CLP seem to be growing more obscure. Until this press conference, the library had consistently said that it estimated the cost of the renovation to be $300 million and that it had been promised $150 million from New York City and expected to raise about $200 million more by selling the properties that currently house the Mid-Manhattan Library and the Science, Industry, and Business Library. Indeed, in June, the library quietly sold five floors of the science library for $61 million. In a New York Times article published the morning of the December 19 press conference, however, the library gave a new explanation for the sources of the CLP’s funds. The library still says that $150 million is going to come from the city, but according to the Times, it now claims that $50 million is coming from the 2008 sale of the Donnell branch and $100 million from the sale of the Annex, an offsite storage space on West 43rd Street, as well as from the sale of several floors of SIBL. I can’t quickly find the date that the Annex was sold, but I think it was before 2008. (UPDATE, 7 January 2013: I guessed wrong. It turns out that the library sold its West 43rd Street annex for $45 million in August 2011.) At the bottom of an ink-on-paper press release, the library adds this sentence: “The Central Library Plan is a unique public-private partnership made possible with generous support from Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, City Council Speaker Christine C. Quinn, the New York City Council, the Empire State Development Corporation, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, Stephen A. Schwarzman, Abby S. Milstein and Howard P. Milstein, and an anonymous donor.” The allocation from the city explains the politicians’ names, and the Milsteins’ names are accounted for by their gift for the Bryant Park storage facility. By also listing Schwarzman and an anonymous donor, the library seems to be suggesting that it considers their gifts, too, to be sources of the CLP’s financing. If you add up all these sources of money, you get a sum twice as large as what the library claims that the CLP will cost. I doubt there’s anything very fishy here. I suspect that the conflicting accounts mean only that the library plans to spend down its endowment—to which the sale of the Annex, the sale of the Donnell, Schwarzman’s gift, and other gifts have contributed—in order to pay for the reconstruction, and then plan to replenish the endowment by selling the Mid-Manhattan and Science, Industry, and Business properties. One last financial note: In its press release, the library now concedes that “we expect the actual budget to be somewhat higher” than the previous estimate of $300 million.)

Asked about modifications to the building, including the possibility of an entrance directly into Bryant Park, Marx said that the cloak room at the north entrance of the building, on 42nd Street, would be “opened up.” He said that four revisions to the building would require approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission: replacing a stretch of wall on the south side of the building with a new loading dock, installing a new air conditioning unit on the roof, converting two windows on the west façade into emergency fire exits, and modifying several windows so that they could open during a fire if necessary. As for a Bryant Park entrance, Marx said he personally thought it would be a great idea, but that the library had decided against it, so as not to compromise the western façade and in order to be “mindful of the park’s interests.”

Someone asked what lessons the library had learned from Hurricane Sandy. Had the library taken sufficient precautions against flooding? Would it acquire a new emergency generator? Yes, Marx replied, the library will have a new emergency generator. As for flooding, he noted that the Bryant Park Stack Extension is built on the foundations of a 19th-century water reservoir, whose retaining walls are 16 or 17 inches thick. An inspection after Sandy discovered no leakage. Flooding from above is not a danger, either, he said; sea levels would have to rise 55 feet before they could reach Bryant Park.

A final questioner asked why the library couldn’t simply improve the air conditioning in the stacks. Marx asserted that it would cost $50 to $75 million to bring the air conditioning up to the level the library wants, and that the stacks would in that case remain vulnerable to fire.

Further impressions

I’m still thinking about my position in this debate. As I’ve said, I’m grateful that the library has agreed to store more books under Bryant Park. Nonetheless, I still wish that the library were leaving the 42nd Street building alone and instead doing a stand-alone renovation of the Mid-Manhattan Library, as I suggested in the spring. There’s a hint that such an alternative might be more feasible than ever. In October, the New York Times reported that Mayor Bloomberg is pushing to re-zone midtown so as to allow for more skyscrapers. The Mid-Manhattan Library is just outside the border of the proposed new zone, and if the city were to draw the new perimeter so as to include the MML, the library might be able to pull off on that site the sort of bold but money-making construction project that the Museum of Modern Art managed a few years ago. In any case, even if the CLP now has too much political momentum to be stopped, there’s something to be said for continuing to pay attention and for trying to hold the library to its promise to sustain its research mission.

I’m not terribly impressed with Foster’s architectural plans, but in his defense, it should be said that the constraints on his design are considerable. As Foster himself noted, the space of the Rose reading room is comparable to the space below it, so one way to imagine the new space is to stand in the Rose and consider how the space downstairs differs from it. The windows in the lower space are narrower than those in the Rose and admit less light. There are windows on two sides of the Rose reading room but only on one side of the space below. The windows in the Rose are raised well above the street, but those in the space below look out onto the backs of two restaurants that abut the library, blocking a considerable portion of the view, especially on the southern half of the western facade. The Rose has only one floor, but four levels will be sandwiched into the space below. The Rose is an echoey space, but visitors to it are asked to be quiet. Will noise be a problem in the space below?

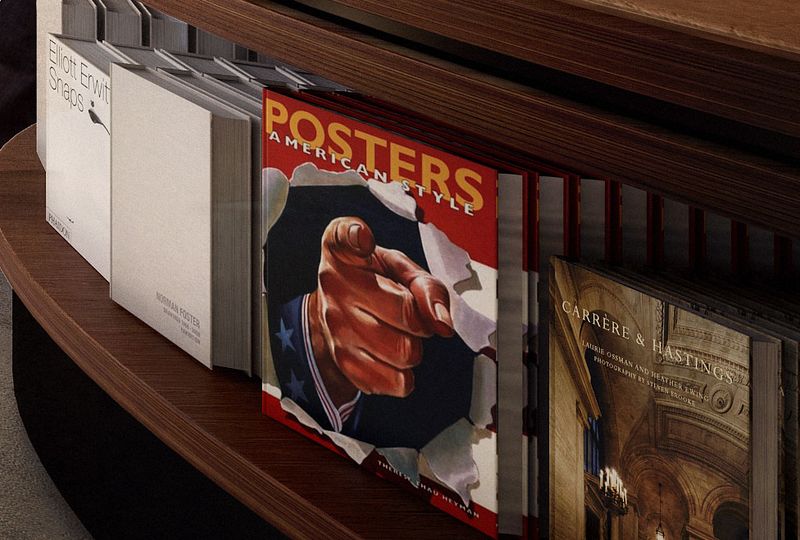

Foster and Marx emphasized in their remarks that the new space will be built so as to be easily repurposed if the library’s needs change. That flexibility is prudent, but it’s disappointing that Foster’s design gives little sense of his vision of the library’s needs now. What function or functions is this form meant to serve? At the press conference, it seemed to me telling that Foster hadn’t considered the problem of how to bring books into the Rose reading room. More than a few people I’ve spoken with have likened the new space to an airport lobby, perhaps because it’s so little shaped by the purposes that people have when they come to a library. Where’s the check-out? Where do you return books? Where will visitors access the catalog? If catalogs are not going to be a first resort, will there be other ways for visitors to discover what the library has to offer? It’s been pointed out to me by several people that in the architectural renderings released by Foster, multiple copies of books are displayed on shelves face out, as they sometimes appear in bookstores, rather than single copies spine out, as they almost always appear in libraries. (See the image detail at the top of this post for an example, which displays a Norman Foster monograph next to one on the New York Public Library’s original architects, Carrère and Hastings.) Will music and film be lent, or only books? Will there be computers for people who don’t own one, and if so, where? Are there going to be places in the new library where book groups can meet, or where job applicants can learn how to shape a resume? Where’s the information desk? Which shelves will be for ready reference, and which for books to be checked out, and how close will the two kinds of shelves be to desks? Or will the library encourage visitors to use online reference sources? Where are the librarians, and how will the design shape their interaction with patrons? I understand that preliminary sketches can’t be expected to answer all these questions, but it seems fair to expect the general principles with which these problems will be approached.