I think the best books of history are those plucked when the matter is ripe—when archives have accumulated and have been opened, and witnesses survive, though enough time has passed to loosen their tongues. A historian with the energy and methodicalness to fossick through the archives and interview the witnesses at that point will strike gold, if, in addition, he has a writerly gift.

In To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement (Princeton, 2024), Benjamin Nathans has written such a book. It’s the tale of the dissident movement in the USSR, which was sparked, in the early 1960s, by a mathematician named Alexander Volpin, who, after four bouts of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, read the Soviet Code of Criminal Procedure and realized that his government had not followed its own rules in its handling of him. A decade earlier, following Khrushchev’s exposure of Stalin’s wrongdoing, the Soviet criminal code had been revised to strengthen legal protections around defendants and witnesses. Volpin, who does, alas, seem to have been not altogether sane, and was very literal-minded, hit on the idea of insisting that the Soviet government follow these rules—a civil-disobedience strategy sometimes referred to as legalism and sometimes as “civil obedience.”

I happened to pick up Nathans’s book at a moment when I was ready, for a variety of reasons, for it to speak to me. Nathans makes clear that the Soviet Union’s dissident movement was able to sprout only because the country’s rulers had made a collective decision, following the mass deaths and bloody internecine feuds of the Lenin and Stalin eras, to move away from brutality. Khrushchev repudiated Stalin’s tyrannies, and Brezhnev brought about “stability of cadres,” an end to the cycles of purges and show trials. The new dispensation saved wear and tear on the rulers’ own skins but also propagated a general social peace—a “respite from history” [495]. Once the reign of the proletariat had been safely achieved, the Soviet state, Brezhnev and his successors felt, no longer needed violence as a political weapon. Also, and perhaps more crucially, rulers in later generations no longer had the same appetite for torture and terror as the founders. They just couldn’t stomach any more, which imparts to Nathans’s story a certain fairy-tale-like quality, at least for a reader in contemporary America, where the rulers have recently tasted blood and have become excited by the discovery that they relish its savor.

By the middle of the 20th century, the supremacy of Communism as an ideology had indeed been achieved in the Soviet Union—the country’s leaders weren’t mistaken about that. The Soviet nonconformists disliked the term dissident and preferred to call themselves inakomysliashchie (“other-thinkers”) [13], but few if any of them thought so otherly that they hoped to overturn the regime or aspired to call Communism into doubt. “They did not seek to capture the state,” Nathans writes; “theirs was a mission of containment by law” [197]. Yuli Daniel’s defense was typical, when he was interrogated nineteen times, in 1965, about a pessimistic novel he had written: he maintained that “I wrote my works not against the Soviet system, but against violations of the Soviet system” [61]. Having left the bloodshed of Stalin’s era behind, Nathans explains, the country declined into what he calls a “lip-service state,” a hypocritical truce between rulers and ruled. A famous piece of black humor captured the cynicism of this truce in economic matters: “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work” [18]. Dissidents were disturbers of this quiescent peace. They were people who believed the political fables they had been told a little too earnestly, and when they ran into an injustice, couldn’t keep their disillusionment to themselves. “Every orthodoxy houses the seeds of its own potential disruption,” Nathans observes [277]. In the case of the Soviet Union, the most dangerous seed was sincerity.

Nathans’s book also spoke to me for personal reasons. I’ve been reading about the dissident movement in the former Czechoslovakia ever since Disturbing the Peace, Karel Hvížďala’s book-length interview with Václav Havel, came out in English in 1990. After a visit to Czechoslovakia, I translated the first biography of Havel, by Eda Kriseová, published in English in 1993, and I’ve continued to read and write about the place. The Soviet movement looms large in histories of the dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, but it looms from off-stage, and I’ve long wished I knew more about it. The Soviet Union famously crushed Czechoslovakia’s experiment with “socialism with a human face” in 1968, by means of a military invasion, and I’ve often wondered, for example, whether the invasion, and the Czechoslovak experiment generally, figures as largely in Soviet as it does in Czechoslovak accounts. (Losing the thirteen colonies, after all, is not quite as big a deal in British historiography as it is in American.)

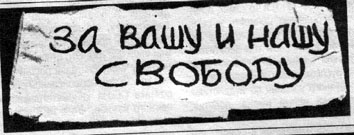

In fact, at least according to Nathans, the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia seems to have been a very big deal to Soviet dissidents. “Nobody took the Soviet side,” a Soviet physicist-turned-dissident later recalled [244], though the regime tried mightily, through the media and by means of staged demonstrations, to create the impression that popular support for the invasion was total. When Soviet dissidents decided to crack this facade by holding a public protest in Moscow’s Red Square, it “became the most celebrated fifteen minutes in the history of the Soviet dissident movement,” Nathans writes [253]. One participant, Larisa Bogoraz, tried to explain her motivations at her trial:

I found myself facing a choice: to protest or to keep silent. For me, keeping silent meant associating myself with the approval of actions of which I do not approve. To keep silent meant to lie. . . . It was precisely the demonstrations, the radio, the reports in the press about universal support [for the invasion] that aroused me to say: I am against this, I do not agree. [262]

Only eight people took part in the demonstration. For the most part, Nathans reports, “they barely knew each other” [252]. That’s very different from the Czechoslovak milieu, where personal connections, often established in the cultural sphere, linked many dissidents together before they became dissidents. As time passed, the Soviet and the Czechoslovak social maps seem to have grown more similar; Nathans reports that in Sacred Paths to Willful Freedom, a 1972 satiric novel about the Soviet dissident community, which circulated in samizdat, “Almost everyone is sleeping with someone other than their spouse” [533]—an endemic state of affairs (as it were) in Czechoslovakia. The other major difference between the two countries’ movements is that a plurality of Czech and Slovak dissidents came from the humanities and the arts—they were playwrights, actors, novelists, musicians, philosophers, and essayists—and a plurality of Soviet ones were scientists or mathematicians. The two movements had, as a result, distinctive flavors. The Soviet movement, even in its late, everybody-is-in-bed-with-one-another phase, seems to have had a certain abstract character, which caused it to keep being reinvented after repeated quashings, as if it were a crystal that couldn’t help but be re-precipitated from the general solution of Soviet political culture. In its early days, its main engine was what Nathans refers to as a “chain reaction”: dissidents would insist on making transparent the processes of the Soviet judiciary, which would get them arrested, which would lead to more trials, and more opportunities for difficult transparency. Via samizdat—texts that were retyped by hand, with as many carbon copies as feasible, and personally distributed—the trial transcripts reached a wide audience, and scientists, even though they were often sheltered and even pampered by the Soviet government, seem to have been more likely to be activated by reading them, perhaps because they were predisposed by their training to feel the need to set right inconsistencies between received opinion and the actual state of the world.

Here, too, there was convergence; eventually the Czechs and Slovaks also adopted the Soviet strategy of civil obedience. Czechoslovakia’s famous Charter 77 movement borrowed its central concept from Moscow’s Public Group to Assist in Implementing the Helsinki Accords: hold Communist leaders accountable for respecting human rights, as the leaders had sworn to do when they signed the 1975 Helsinki Accords, in exchange for which promise they had been granted formal international recognition of their nations’ borders for the first time since World War II. Kissinger and the diplomatic community pooh-poohed the human-rights language in the treaty as mere boilerplate; George F. Kennan, Nathans reports, dismissed it as “high-minded but innocuous” [599]. The dissidents took the promises seriously. (Even during this campaign of pretending to believe the government meant what it said, however, the predominant style in Czechoslovakia was ironic. “I know you’ll put all this into one of your articles,” an interrogator told the Moravian dissident Ludvík Vaculík during an interrogation, soon after Charter 77 was announced. “It was no use—they know everything,” Vaculík concluded, jestingly, in an essay about deciding not to share with his interrogator any of the nice apples he’d recently picked in the countryside.)

Another major difference between the movements is that in Czechoslovakia, as in other Soviet satellites, dissidence was buttressed by at least a tinge of nationalism, which in those countries had never been fully dissolved in the international fraternity of socialism. I think it made a difference, too, that Communism took hold in Russia at the end of World War I, and in Czechoslovakia not until a few years after the end of World War II. Russia never had all that much of a bourgeoisie in need of crushing in the first place, and by mid 20th century, it was more or less extinct. Socialism had brought millions out of poverty, but the country’s intelligentsia was a thin, artificially created layer of the population, less a “middle” class than a “between” class, for the most part gray and anemic because “we all have the psychology of government workers,” the dissident Andrei Amalrik wrote in Will the Soviet Union Survive until 1984? (1969), a samizdat analysis of the social composition of his movement and of the USSR more generally [304–10]. Key to the “chain reaction” of difficult transparency in the Soviet Union were open letters, to which dissidents often added their professions beneath their signatures. Analyzing this dataset, Amalrik found that among dissidents “the single largest contingent,” Nathans writes, “worked at institutions of higher education” [305]. For a class of thinkers sustained by a single universal employer to oppose the power of that single universal employer is a tricky balancing act. Officially, by the mid 1960s, there was no middle class in Czechoslovakia, either, but the Havel family, to take a crucial example, had been among the grandest of the great bourgeois families of the First Republic, the democratic and capitalist interregnum in Czechoslovakia between the two world wars. The Havels were real estate developers who pioneered the country’s nascent film industry. All but two rooms of their six-story Prague townhouse had been nationalized by the time Havel started writing plays, but it would have taken at least one more generation of class struggle to prevent any social and intellectual capital from being passed on to him. Dissidents in Czechoslovakia may have stood on economic ground no sturdier than what dissidents in the Soviet Union stood on, but the displaced social order was still a living memory for them, and they were able to speak with a cultural authority that hadn’t quite dissipated.

By relaying Nathans’s insight that Soviet leaders in the late 20th century were trying to move past violence, I hope I’m not giving the impression that the country’s dissidents had it easy. The Soviet authorities remained relentless, even if they were no longer quite as ruthless. Nathans devotes chapters to the “dissident repertoire” and to the repertoire of the secret police assigned to crush them, and the disparity is extreme. In a psychological rebound from the formality of Soviet life, dissidents seem to have been allergic to formally organizing themselves, and to have preferred for each person involved to be acting on the promptings of his individual conscience. Their weapon of choice was the open letter, circulated in samizdat. Even their dissident newspaper, the Chronicle of Current Events, was decentralized and intermittent. At first the authorities arrested and tried dissidents, hoping to repeat the pedagogical effects of the show trials of the early Soviet Union, in which bludgeoned defendants publicly confessed to everything and more, but the authorities soon learned that absent the bludgeonings, trials accelerated the dissidents’ “chain reaction,” because even though the judgments went as foreordained, defendants got a chance to speak for themselves. Authorities came to rely instead on extrajudicial means of suppression: involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations, “prophylactic” conversations (intimidating visits from KGB officers), and internal and external exile.

These were efficacious. By the early 1980s, the free-ranging Soviet dissident was an endangered species. Andrei Sakharov was banished in 1980, and after the Chronicle of Current Events ceased publication in 1982, the dissident movement all but shut down [609]. And then, a decade later, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev started echoing dissident catchwords like transparency and reform, and shortly after Gorbachev loosened the stays, the straitjacket unraveled. Whether the dissident movement had anything to do with the end of the Soviet Union remains a debated question. Nathans argues, hopefully, that “the dissident movement sparked by Volpin helped drain the Soviet system of legitimacy inside them,” [614] and maybe that is how the spirit of history did its work, in this case. Unfortunately, the current state of politics in Russia does not grace the story with a happy ending. In his 1969 samizdat essay, Amalrik had guessed that if the Communist regime collapsed, dissidents, and the middle class they came from, would be too weak to lead Russia, and the likely result would be “the rise of virulent Russian nationalism ‘with its characteristic cult of strength and expansionist ambitions'” [309]. In a 1967 essay, Sakharov had predicted that the Soviets and the West would someday converge, combining the best of both worlds [285], but his fellow dissident Leonid Plyushch thought the convergence more likely to be a dark one, with the USSR descending into “state capitalism in its most inhuman form” while the West became “less democratic, [with] greater concentrations of capital, and merging monopolies with the state” [292]. Ah well. Being right about the future doesn’t necessarily mean it turns out any better.

And maybe one doesn’t become a dissident because one thinks it likely one will prevail. Discussing the source of Larisa Bogoraz’s radical drive for transparency, Nathans quotes an essay by Hannah Arendt, “Moral Responsibility under Totalitarian Dictatorships,” about what motivated resistance to Nazi rule. Protesters, Arendt maintained, acted

not because the world would be better (not because of political responsibility) and not because they were worried about the salvation of their soul, but because they wanted to go on living with themselves. [292]

![A pen-and-ink drawing of a skinny man with a giant eyeball for a head. The handwritten caption is a quote from Emerson's Nature: "Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, & uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball." Christopher Pearse Cranch, "Illustrations of the New Philosophy," drawings, [ca.1837-1839] (MS Am 1506). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. A pen-and-ink drawing of a skinny man with a giant eyeball for a head. The handwritten caption is a quote from Emerson's Nature: "Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, & uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball." Christopher Pearse Cranch, "Illustrations of the New Philosophy," drawings, [ca.1837-1839] (MS Am 1506). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.](https://steamthing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/8367159-626x1024.jpg)