My review of “The Art of the American Snapshot, 1888–1978: From the Collection of Robert E. Jackson,” a photo exhibit with a catalog, is in the 1 May 2008 issue of New York Review of Books (online subscription required). Since the article does have footnotes, I don’t need to annotate my sources here, so I thought instead I would post a few snapshots from my own collection, and then throw in a few motley links.

The snaps of “Belle” (left), a child with a French bulldog (right), and an Edwardian picnic (below) are anonymous. I purchased them in Brooklyn sometime in the last half dozen years. I’m afraid I don’t remember where. I find it very calming to imagine attending a picnic with fruit and thermoses anchoring the tablecloth. In white tie, of course.

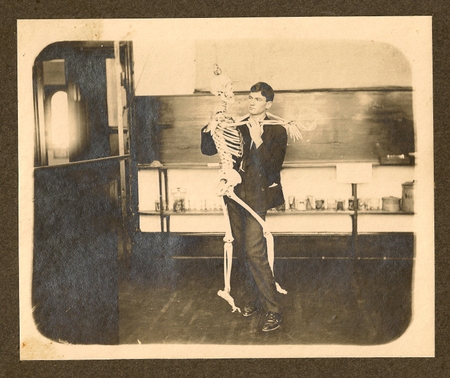

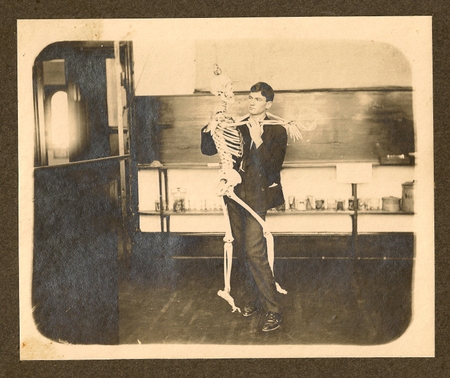

The medical student dancing with the skeleton (below) is my maternal grandfather. As you can see, a complicated man.

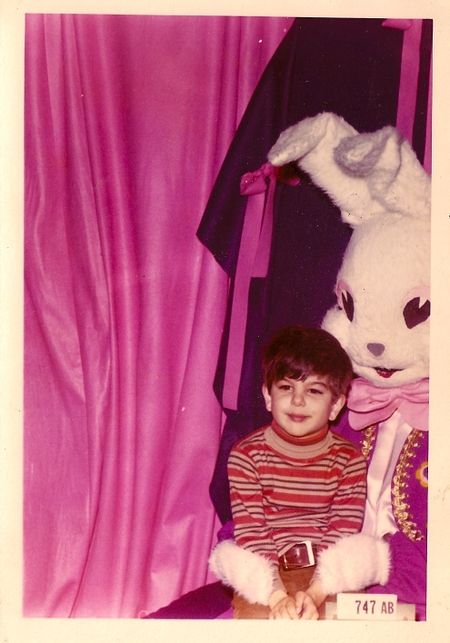

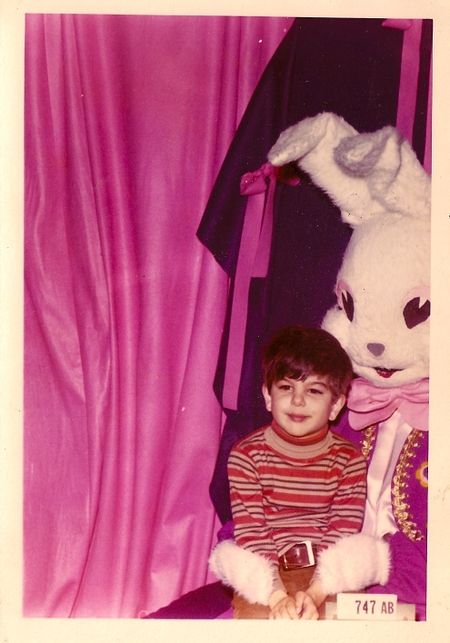

And this fellow (left) grew up to be my boyfriend. Note the placid, almost beatific smile. Contrast it with the eerie human eye just barely visible, in a shadowy way, inside the fake eye of the bunny creature. Note, too, the fluffy, imprisoning hands of the bunny creature.

Now, as to links. Snapshots—or, to call them by their fancy mass-noun, vernacular photography—are very well suited to the Internet. You can lose yourself for days looking through all the virtual shoeboxes. Luc Sante’s great blog, Pinakothek, often features found photos. Another blog, Swapatorium, has photos retrieved from flea markets and junk shops. A number of collectors have put their finds online, including Nicholas Osborn at Square America and John and Teenuh Foster at Accidental Mysteries. If you decide to start collecting yourself, there are images for sale at the Found Photo and at Project B.

A number of people have sent scans of their old photos to NYU’s Collective Visions, along with prose-poetical annotations (it doesn’t look as if it’s been updated recently, though). When the Getty ran a snapshot exhibit several years ago, they hosted a similar volunteer, communal snapshot gallery on their website. Polanoid pools the Polaroids made and collected by the dying company’s aficionados, though not all the images are snapshots. And then of course there’s Flickr. Almost every historical archive with images has some vernacular photography in it, but at the risk of seeming arbitrary I’ll single out the Charles Van Schaick collection in Wisconsin Historical Society, which has such treasures as this cake, and the Charles Weever Cushman photograph collection at Indiana University, the bequest of an amateur whose snaps sometimes call to mind the great color photos of the FSA/OWI held by the Library of Congress (which aren’t snapshots, properly speaking, at all).