Before I started reading for my recent New Yorker article “It Happened One Decade,” I hadn’t actually read James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) all the way through. I vaguely recall that I was supposed to have done so in college, but I didn’t. That’s probably a good thing, according to comments that Evans made in 1974 when his photographs were exhibited at the University of Texas at Austin. Agee “wouldn’t approve of reading Let Us Now Praise Famous Men for a class assignment,” Evans wrote, “because it robs the work of its freedom. Agee was never reasonable about the heavy hand of duty.”

Reading it at age forty-two, however, I kind of loved it, even if (like Morris Dickstein, the author of the book I was reviewing) I couldn’t help but roll my eyes at the portentous table of contents and other elements of gratuitous “structure.” This excess does have its rewards, however, including a sense of depth—a sense of the complexity of reality. Several times over, from different perspectives, Agee describes the home of the family whom he calls the Gudgers (in real life, their last name was Burroughs), and different aspects emerge each time. On page 153 (of the Houghton Mifflin edition), for example, Agee writes that the family’s

left front room is used only dubiously and irregularly, though the sewing machine is there and it is fully furnished both as a bed room and as a parlor. The children use it sometimes, and it is given to guests (as it was to us), but storm, mosquitoes and habit force them back into the other room where the whole family sleeps together.

Agee returns to the room much later in the book, on page 419, when he finally gets around to describing the first night that he spent with the Gudger/Burroughs family. He describes the parents “telling me where I would sleep, in the front room” and then describes the “waking and bringing-in of the children from their sleeping on the bed I was to have.” There’s a touch of inconsistency between these observed facts and the general observation made earlier, and it occurred to me that the Burroughses, wanting to be hospitable, may have told Agee a white lie about how often the children used the room. Surely a family with so few resources would have made regular use of a bedroom that they kept furnished, even if it was drafty. If it were true that the Burroughs children didn’t often sleep in the bedroom because it was too easy for mosquitoes and rain to get in, why were the children sleeping there on the night of Agee’s arrival, which took place in July, during a downpour? Of course it only makes the Burroughs family seem even more appealing to think that they might have fibbed to help Agee feel at home.

Among the book’s many pleasures is comparison of Agee’s prose descriptions of the tenant farmers’ habitats with Evans’s photographs of them. At the start of the section titled “A Country Letter,” for example, Agee describes in detail a coal-oil lamp in the Burroughs’ house:

The glass was poured into a mold, I guess, that made the base and bowl, which are in one piece; the glass is thick and clean, with icy lights in it. The base is a simply fluted, hollow skirt; stands on the table; is solidified in a narrowing, a round inch of pure thick glass, then hollows again, a globe about half flattened, the globe-glass thick, too; and this holds oil, whose silver line I see, a little less than half down the globe, its level a very little—for the base is not quite true—tilted against the axis of the base.

If you turn to the front of the book, you can see the lamp he’s talking about and verify his description of its shape and its tilt, in a Walker Evans photo, which, like many of the photos that Evans took of Alabama’s tenant farmers, is also available in a high-resolution scan at the Library of Congress. Agee describes the graniteware washbasin visible in the same photo toward the end of “A Country Letter” and again in a later section titled “The hallway; Structure of the four rooms.” In the section “Shelter,” he gives a lengthy ekphrasis of a decorated mantelpiece at the Burroughses’, down to the whitewash print of a child’s hand to one side of it. In Evans’s photo, available at the Library of Congress and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s also some graffiti above the mantel, unmentioned by Agee. I wasted some time trying to decipher it from the high-quality scan, but without success. Any guesses?

If you turn to the front of the book, you can see the lamp he’s talking about and verify his description of its shape and its tilt, in a Walker Evans photo, which, like many of the photos that Evans took of Alabama’s tenant farmers, is also available in a high-resolution scan at the Library of Congress. Agee describes the graniteware washbasin visible in the same photo toward the end of “A Country Letter” and again in a later section titled “The hallway; Structure of the four rooms.” In the section “Shelter,” he gives a lengthy ekphrasis of a decorated mantelpiece at the Burroughses’, down to the whitewash print of a child’s hand to one side of it. In Evans’s photo, available at the Library of Congress and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s also some graffiti above the mantel, unmentioned by Agee. I wasted some time trying to decipher it from the high-quality scan, but without success. Any guesses?

In his collaboration with Agee, Evans was funded by the government’s Farm Security Administration, and the copyright of his photos are now owned by the public and many of his original prints are in the care of the Library of Congress. In addition to individual photos, the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division has digitized two albums, containing slightly more than a hundred prints (update: this is now a better link, that Evans assembled to document his trip with Agee. (If you click on one of the albums at the top of the page, you can then flip through it in an online reader page by page.)

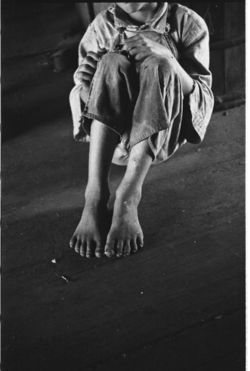

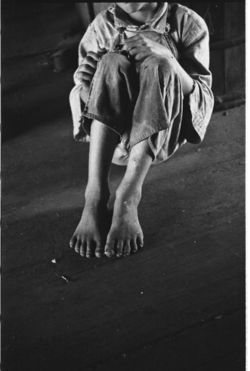

Most of the photos that Agee glosses are printed in the front of his book, and a few more may be found online in the Library of Congress’s two albums. To find still more photos, search the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division for ‘Walker Evans Alabama’ or for ‘Walker Evans’ and the name of one of the tenant-farming families (‘Burroughs’, ‘Tingle’ [sometimes spelled ‘Tengle’], or ‘Fields’). Once you do this, click on ‘Display Images with Neighboring Call Numbers’ if you want to see Walker Evans photos in the Library of Congress that haven’t been given titles or otherwise indexed. That’s the only way to find this portrait of the children Floyd Lee Burroughs Jr. and Othel Lee Burroughs, this alternate portrait of Floyd Burroughs on his porch or this one of him on a mule, or this enigmatic close-up of one of the Fields children.

Most of the photos that Agee glosses are printed in the front of his book, and a few more may be found online in the Library of Congress’s two albums. To find still more photos, search the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division for ‘Walker Evans Alabama’ or for ‘Walker Evans’ and the name of one of the tenant-farming families (‘Burroughs’, ‘Tingle’ [sometimes spelled ‘Tengle’], or ‘Fields’). Once you do this, click on ‘Display Images with Neighboring Call Numbers’ if you want to see Walker Evans photos in the Library of Congress that haven’t been given titles or otherwise indexed. That’s the only way to find this portrait of the children Floyd Lee Burroughs Jr. and Othel Lee Burroughs, this alternate portrait of Floyd Burroughs on his porch or this one of him on a mule, or this enigmatic close-up of one of the Fields children.

Still more images may be found at the Walker Evans Archive of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it’s easy to compare the stoic close-up portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs (Annie Mae Gudger) that Evans chose to print in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men with her sly smile in two variants. (Here’s yet another, from the Library of Congress, which was reproduced in Evans’s American Photographs of 1938.) The Met also has a striking image of Floyd Burroughs in profile, which I’ve never seen anywhere.

Though the photographic archive is abundant, there are intriguing lacunae. A few times, Agee describes photos taken by Evans that don’t seem to correspond to images available anywhere online or in any publication that I’ve looked in. At the bottom of page 364 and top of page 365, for example, Agee describes a picture of the Ricketts (Tingle) family thus:

there you all are, the mother as before a firing squad, the children standing like columns of an exquisite temple, their eyes straying, and behind, both girls, bent deep in the dark shadow somehow as I listening and as in a dance, attending like harps the black flags of their hair

Perhaps Agee is describing the original from which Evans cropped this image? (There’s a better version at image 24 of the second of the two albums mentioned above; update: here’s a better link.) It’s impossible to know.

There’s another ghost photo on page 369, when Agee describes a family portrait of the Burroughses:

The background is a tall bush in disheveling bloom, out in front of the house in the hard sun: George [Floyd] stands behind them all, one hand on Junior’s shoulder; Louise (she has first straightened her dress, her hair, her ribbon), stands directly in front of her father, her head about to his breastbone, her hands crossed quietly at the joining of her thighs . . . ; Burt sits at her feet with his legs uncrossing . . . ; and there again they are; the three older of them thoroughly and quietly serious, waiting for the shutter to release them . . .

I have no idea where this image is, if it survives. At least one Evans portrait of the Gudgers/Burroughses as a family does survive. It’s reproduced on the cover of William Stott’s Documentary Expression and Thirties America, and is held by the Walker Evans Archive at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, source of the image to the right. As you can see, though, the family is standing in front of their house in this image, not in front of a bush, and the configuration of persons is slightly different from what Agee describes.

I have no idea where this image is, if it survives. At least one Evans portrait of the Gudgers/Burroughses as a family does survive. It’s reproduced on the cover of William Stott’s Documentary Expression and Thirties America, and is held by the Walker Evans Archive at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, source of the image to the right. As you can see, though, the family is standing in front of their house in this image, not in front of a bush, and the configuration of persons is slightly different from what Agee describes.

Toward the end of his book, Agee describes images of a naked infant boy and naked infant girl, but it isn’t clear from his wording whether the images were photographed by Evans or existed only in Agee’s mind’s eye. In any case, it seems likely that someday even more photographs by Evans of the families in Agee’s book may turn up, perhaps in the form of negatives that the Library of Congress has yet to digitize. In conclusion, and just for the hell of it, here’s a link to a funny picture of Evans himself, taken by the great Helen Levitt, which was recently donated to the Museum of Modern Art.