The documentarians Corie Trancho and Alexis Robie have been photographing and writing about Officers’ Row, a group of condemned buildings at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, sometimes called Admirals’ Row. Their online archive is haunting, and I recommend a tour of it. There are movements afoot to try to save the houses, though the documentarians are staying neutral.

To the best of Trancho and Robie’s knowledge, the houses weren’t built until 1860 at the earliest. No doubt they’re right, but Henry James seems to have thought they were older. While re-reading Portrait of a Lady recently, two things jumped out at me. First, James introduces Madame Merle the same way Melville does Queequeg— by a sequence of misconceptions. Ishmael first thinks Queequeg is an injured white man, then a tattooed white man, then the devil, then a savage, then a cannibal, and finally a suitable bedmate. Isabel thinks Madame Merle is an artist, then a Frenchwoman, then an American, then a “very attractive person,” then “a person of tolerably distinct identity,” and finally a suitable confidante.

Second, and more relevantly, it leaped out at me that Madame Merle was born in Officers’ Row:

Madame Merle glanced at Isabel with a fine, frank smile.

“I was born under the shadow of the national banner.”

“She is too fond of mystery,” said Mrs. Touchett; “that is her great fault.”

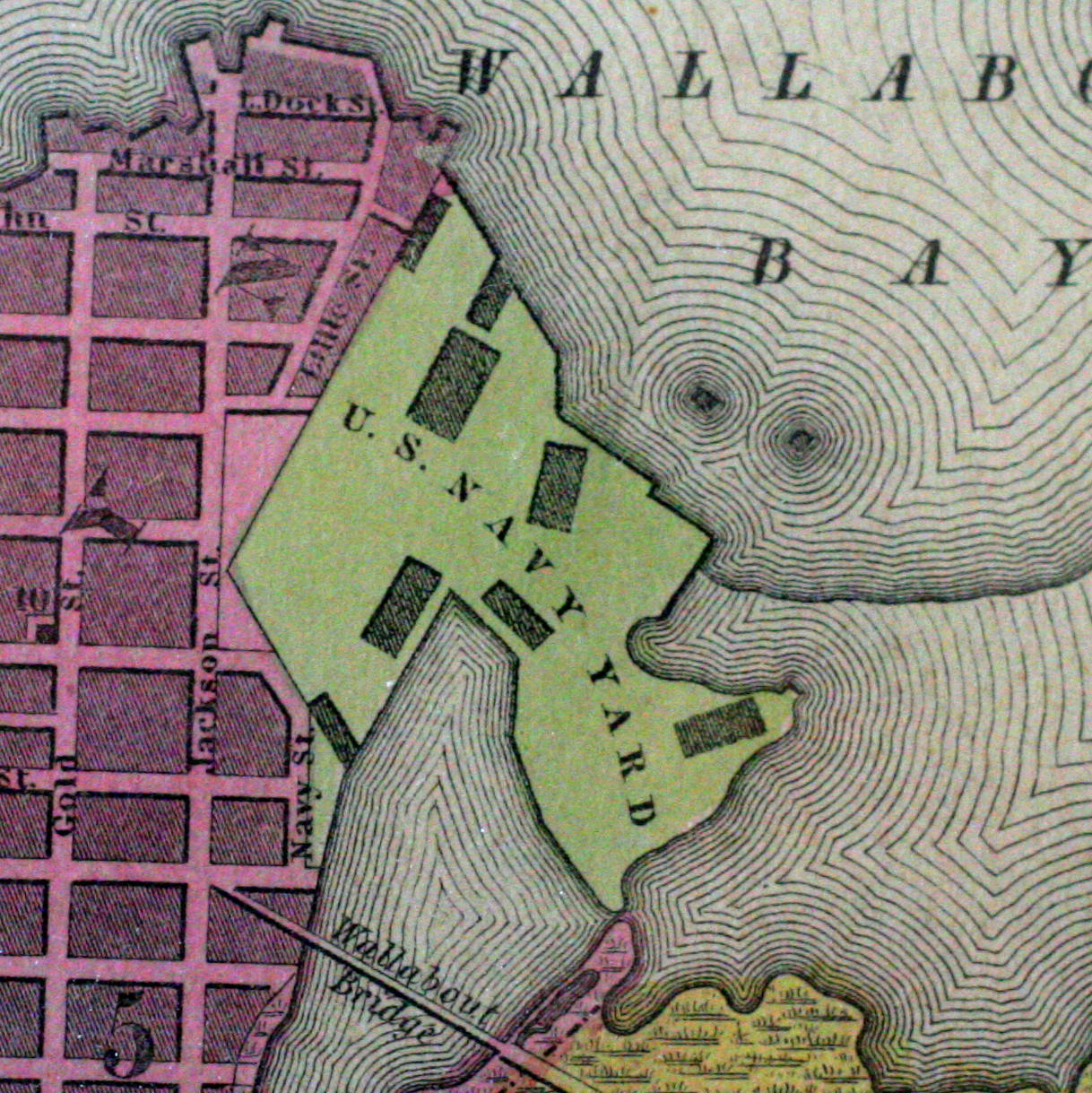

“Ah,” exclaimed Madame Merle, “I have great faults, but I don’t think that is one of them; it certainly is not the greatest. I came into the world in the Brooklyn navy-yard. My father was a high officer in the United States navy, and had a post— a post of responsibility— in that establishment at the time. I suppose I ought to love the sea, but I hate it. That’s why I don’t return to America. I love the land; the great thing is to love something.” (chapter 18)

At least, that’s where Madame Merle says she was born. Whether you believe what she says is at your option. She’s about forty at the time of the novel, which seems set in a moment contemporary to its publication, in 1880-1881; in James’s imagination, then, the row, or a predecessor to it, was standing in the 1840s.