My boyfriend, Peter Terzian, has just published three great pieces. One is available online, a deft review in Newsday of Jenny Uglow’s biography of Thomas Bewick, the engraver of rural scenes who was a contemporary of Wordsworth. When you next visit a newsstand, you should also pick up the July/August issue of Columbia Journalism Review for his interview with environmental historian Rebecca Solnit, and the July/August issue of Modern Painters for his review of Novels in Three Lines, the microfiction romans durs of Félix Fénéon.

Category: items new in print

Notebook: Aimee Semple McPherson

“The Miracle Woman,” my review of Matthew Avery Sutton’s biography Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America appears in the 19 July 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books. (It’s not available for free online. Please subscribe! Otherwise someday there will be no more steamboats…) What follows is supplemental, and not likely to make sense until you read the article.

As ever, my first thanks are owed to the book under review. A couple of other sources made it into the article’s footnotes: Edith L. Blumhofer’s Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody’s Sister (Eerdmans, 1993) and Daniel Mark Epstein’s Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson (Harcourt, 1993). Since I didn’t have room in my article to give much sense of these books as books, it may be worth saying here that their styles are quite different: prose-poetical and trusting in Epstein’s case, authoritative and reserved in Blumhofer’s. Sutton praises both of them in his book, and writes that he hurried past McPherson’s youth because they covered it so well, choosing instead to focus on her later years, which they scanted. That’s true of Blumhofer, whose tact constrains her to a cryptic brevity when she reaches the bickering and scandal of McPherson’s last decade. Epstein, though, provides a few more of the late twists and turns than Sutton does, and may in the end give the most complete picture. (Unfortunately, he’s not always perfectly accurate. For example, he writes that McPherson failed to attend her father’s funeral in 1927, but he is contradicted by the obituary he quotes, which states that her father died at eighty-five, his age in 1921. Indeed, Blumhofer reports that McPherson’s father died in 1921, and has evidence, furthermore, that Aimee did return to her hometown for the service.) The other important biography of McPherson is Lately Thomas’s Storming Heaven: The Lives and Turmoils of Minnie Kennedy and Aimee Semple McPherson (Morrow, 1970), which traces McPherson’s path through the pages of American newspapers in great detail; on the subject of McPherson, Thomas notes, the “press record is almost inexhaustible.” The result is somewhat unfiltered and “bitty,” as the English say, but the newspaper photographs that illustrate the book alone make it worthwhile.

In 1999, a University of Virginia undergraduate named Anna Robertson put together a slide show of McPherson photographs, an Aimee Semple McPherson cut-out doll published by Vanity Fair in the 1920s, and a number of other images and documents. There are also pictures on the website for “Sister Aimee,” a PBS documentary that drew on Sutton’s book, and on a webpage about McPherson managed by the Foursqure Church, the Pentecostal denomination she founded.

In his novel Elmer Gantry, Sinclair Lewis modeled the character of Sharon Falconer on McPherson. He described Falconer’s voice as “warm, a little husky, desperately alive,” and that matches McPherson’s, which you can hear preaching about Prohibition at the History Matters website. You can also hear early recordings of McPherson in a 1999 radio program, “Aimee Semple McPherson — An Oral Mystery,” part of NPR’s Lost and Found Sound series.

An odd side note, which I never even tried to sandwich into my article: Blumhofer writes that after Aimee and her second husband, Harold, separated in 1918, Harold preached for a while with “John and Elizabeth Ashcroft, evangelists in Maryland, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania.” From scanning a few online biographies and genealogies, I’m fairly sure that these were the grandparents of former attorney general John Ashcroft.

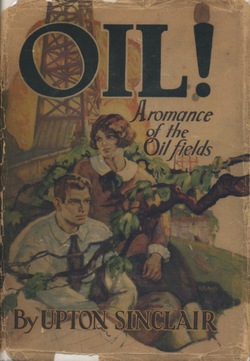

Oh, and the photo above. Aimee Semple McPherson appears as a character in Upton Sinclair’s 1926 novel Oil!, but Sinclair switched McPherson’s sex when he novelized her. Like McPherson, Eli Watkins is a preacher in the Pentecostalist tradition who vanishes and is thought to have drowned; he comes back with a tale of having been held up in the water by three angels, though the rumor is that he spent the missing days in a beachfront hotel with an attractive young woman. That isn’t Eli Watkins on the book’s cover, which is the Grosset & Dunllap edition, because Watkins’s story is really no more than a minor subplot. The novel mostly concerns an idealistic young man, Bunny Ross, who discovers as he grows up that the oil business, which his father works in, corrupts politicians and civic life generally. Eventually Bunny becomes a “millionaire red,” vowing to spend his inheritance on a socialist labor college. When Bunny hears Eli preaching on the radio what he knows to be lies, he thinks to himself,

The radio is a one-sided institution; you can listen, but you cannot answer back. In that lies its enormouss usefulness to the capitalist system. The householder sits at home and takes what is handed to him, like an infant being fed through a tube. It is a basis upon which to build the greatest slave empire in history.

The woman in the illustration may be Eli’s sister, Ruth, a sort of shy shepherdess, who never quite turns into the love interest.

Notebook: Jackson and habeas corpus

"Bad Precedent," my essay on Andrew Jackson and habeas corpus, appears in The New Yorker on 29 January 2007. As with earlier articles, I'm posting here a few outtakes and tips of the hat.

As ever, I owe the most to the book under review, Matthew Warshauer's Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law: Nationalism, Civil Liberties, and Partisanship (available from Amazon and, for the same price, directly from the University of Tennessee Press).

I also learned much from three recent biographies of Jackson, very different in style and perspective. Jackson provokes feelings of surprising intensity, considering that he's a long-dead historical figure, and a great virtue of H. W. Brands's Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times is that it explains the sturm and drang around him in a calm, careful tone. Brands relies for the most part on published sources and doesn't offer new archival discoveries, but he places Jackson in context with impressive clarity, and his narrative is well constructed. (My only quibble is with his reliance, in a few places, on anecdotes about Jackson's early life from an early-twentieth-century account by Augustus C. Buell; Buell's stories were probably fiction, the scholar Milton W. Hamilton asserted in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography in 1956. Of course it's possible that Brands has found reason to dissent from Hamilton's athetization. . . .)

Brands offers a generous but highly readable 600-plus pages. Sean Wilentz's Andrew Jackson, by contrast, is as lean and sinewy as Jackson himself. It also shares with Jackson an appetite for controversy: at 195 pages, Wilentz's book is designed for the reader who wants an introduction to Jackson in the course of an afternoon, but Wilentz manages nonetheless to find room to mount a sophisticated defense of Jackson from attacks by other historians—attacks which, he argues, fail to take account of the political realities of Jackson's day. Among others, Wilentz critiques Andrew Burstein, who, in The Passions of Andrew Jackson, condemns Jackson harshly, as a person and as a leader. Burstein's isn't a straight biography, but rather a study from a perspective that's a little hard to describe—a mixture of social history, psychology, and cultural studies. Burstein scants the political context, which is a rather large piece of the puzzle to leave out. Still, Burstein seems to have immersed himself in the primary sources, and presents evidence, often highly colorful, that is not easy to find elsewhere.

The big books on Jackson are two three-volume biographies: James Parton's, issued in 1859 and 1860, and Robert Remini's, issued in 1977, 1981, and 1984. Parton seems to have had most of the important sources available to him, and he's a beautiful stylist. Here he is setting the scene of New Orleans: "The Mississippi is apparently the most irresolute of rivers; the bed upon which it lies cannot long hold it in its soft embrace." And here he is on the impossibility of recovering the truth about Jackson's duel with legislator Thomas Hart Benton:

Neither the eyes nor the memory of one of these fiery spirits can be trusted. Long ago, in the early days of these inquiries, I ceased to believe any thing they may have uttered, when their pride or their passions were interested; unless their story was supported by other evidence or by strong probability. It is the nature of such men to forget what they wish had never occurred; to remember vividly the occurrences which flatter their ruling passion; and unconsciously to magnify their own part in the events of the past.

All three volumes of Parton's biography of Jackson are in Google Books: volume 1, volume 2, and volume 3. (The image above is the frontispiece to volume 2.) Though Parton sees Jackson's merits, he is not a fan, as Remini sometimes is. Remini is a researcher of great energy and diligence, and I would guess that he's the only person who has discovered more about Jackson than Parton did. I found myself disagreeing with some of his analyses, however. For example, Remini argues that Jackson's New Orleans victory did affect the territorial outcome of the War of 1812, despite the prior signing of the Treaty of Ghent. That seems unlikely to me, on the face of it; moreover, in 1979, in the journal Diplomatic History, the scholar James A. Carr turned to British military correspondence and internal diplomatic memoranda to show that by the end of the War of 1812, the British wanted nothing more than to wash their hands of America and conflict with Americans.

The article by Abraham D. Sofaer that I refer to at the end of the article is "Emergency Power and the Hero of New Orleans," Cardozo Law Review 2 (1980): 233 ff. Also useful, as I was thinking through the legal issues, was Ingrid Brunk Wuerth's "The President's Right to Detain 'Enemy Combatants': Modern Lessons from Mr. Madison's Forgotten War," Northwestern University Law Review 98 (2004):1567 ff. Unfortunately, neither of these is available online for free, though they're easy to find in for-profit databases. In fact, I turned up remarkably few Internet-enhanced multimedia supplemental whirligigs during my tours of Web procrastination this time out, but no Andrew Jackson blog post would be complete without a reference to the large White House cheese, and someone has digitized all of Benson J. Lossing's Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812, which has some of the best battle diagrams going, if you plan to read a blow-by-blow account and want some visual guidance. Of course, the Hamdan v. Rumsfeld decision is online, as is the Military Commissions Act of 2006, and they may be profitably read side by side.

Offprints in a digital age

An article of mine about a nineteenth-century con man and kidnapper is in the latest issue of American Literary History, a scholarly journal, and this morning my offprints arrived. I don’t think the world outside academia knows what offprints are any more, if they ever did. I say this with some confidence because when I gave one to a very worldly and well-read acquaintance, he asked, a few weeks after reading it, what it was. Had I had my essay privately printed? he asked. And that was more than a decade ago. I would like to assure everyone that not even I am so nineteenth-century as to have my essays privately printed.

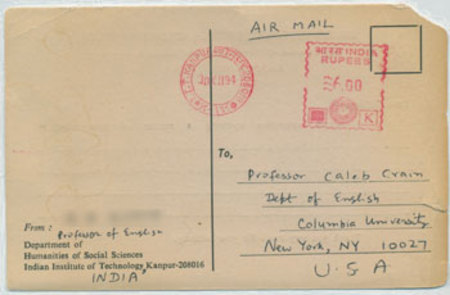

Offprints are unbound printed pages of an article, which a scholarly journal provides to the article’s author so that he may share them with colleagues. The protocol is — or rather, was — that when a researcher wanted to read an article that happened to appear in a journal he didn’t subscribe to, he would send a postcard to the author, care of his institutional address, asking for an offprint. And the author, as a matter of scholarly courtesy, would mail it to him free. My father is a scientist, and when I was little and collected stamps, most of them came from the postcards sent to him and the other scientists at his institution, requesting offprints. In those days, the 1970s and 1980s, the requests by and large came from developing countries, where the research institutions had less money for their libraries. The postcards came from all over the world, in other words, from countries I’d never heard of and imagined I would never see, and it gave me a thrill to see them, emblems of the glamour and global reach of the life of the mind.

It tickled me, therefore, when, upon the publication of my first scholarly article in 1994, I received a request for an offprint.

I mailed the offprint to India very gladly. It was, unfortunately, the last such request I ever got, as well as the first, even though I’ve published several more scholarly articles since then. I don’t know whether offprints are still traded for postcards in the sciences. But in the humanities, at least to my knowledge, the use of them has degenerated to attaching them to job applications or to tenure files. The only people who see them today, in other words, are people operating in a supervisory or fiduciary capacity; the sharing of research is done through online databases like ProQuest, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Offprints are now just prettier versions of a photocopy; including one in your file is roughly equivalent to printing your resume on cream-colored paper instead of on flat white. The romance, in other words, has seeped out of it.

I have two dozen of them on my hands, however. So here’s the proposal: send me a postcard, a real one, on paper, and I’ll mail you an offprint. There is a slight advantage to the paper copy, actually; I couldn’t get online rights for one of the images, so that picture doesn’t appear in JSTOR, only in the printed version. But by and large the only cash value of what I’m offering will be best appreciated by collector geeks, the sort of people who worry whether they’ve been sold an original of the first issue of n+1 or a reprinting. Or for people who, like me, economize on printer cartridges. While supplies last, then, send a postcard to [sorry—address deleted for now, November 2016], and I’ll send you an offprint. Don’t forget to include your own snail-mail address. (If by some miracle I run out, I’ll warn you here.)

Forthcoming, glossy, free

The next article of mine to see print will likely appear in the lavishly illustrated new magazine Culture & Travel, where Peter works as a senior editor. They don’t put very many of their articles online, and it isn’t easy to find on newsstands, so if you’d like to read it, your best bet is to click here and fill out the questionnaire to see if you qualify for a free subscription.