I found this bookplate, unglued but still tucked into the front endpapers, in a history that I spent today reading. The book, which I bought used last week, was published in the 1930s; the Internet tells me that Edwin B. Coddington, its sometime owner, was the longtime chair of Lafayette College’s history department and wrote the definitive history of the Battle of Gettysburg, published in 1968, some time after his death. I like the way the bookplate evokes the idea of American history. I’ve been using it as a bookmark, and I must have looked at it half a dozen times before I had a Sesame Street moment and realized that the Indian and the airplane don’t belong in the same picture.

Category: history of technology

Clash of the titans

Sometime on Friday night, the New York Times reports, Amazon deactivated the Buy Now buttons on its website for all books published by the Macmillan group, including such imprints as Farrar Straus & Giroux, Henry Holt, and St. Martin’s Press. As of this writing, you cannot buy a new copy of the correspondence of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell from Amazon, though it’s still available from Barnes & Noble, Powells, and other indie booksellers. The same is true of thousands of other titles.

This is a bit of a stunner. Macmillan and Amazon have been arguing, it transpires, over the pricing of e-books, but Amazon yanked Macmillan’s ink-and-paper as well as its electronic books—bypassing conventional weapons in favor of first-use nuclear.

As a writer with friends who work at Macmillan imprints, my sympathies are with the publisher. To judge by the comments being left at the New York Times article on the conflict, however, quite a few people are siding with Amazon, in many cases because they believe it’s greedy of publishers to demand higher prices for e-books. Greed, no doubt, exists on both sides, living as we do under capitalism, but greed alone doesn’t explain the dispute. Yes, Amazon wants to sell e-books for $9.99 or less, and Macmillan wants Amazon to sell them for $15 or less. But as Macmillan’s CEO John Sargent explains, in a statement released today as an advertisement to the book-industry newsletter Publisher’s Lunch, Amazon and Macmillan aren’t at the moment fighting to see who can make more money on a book sale. They’re fighting to see who can lose more money. This is a very peculiar battle.

And it may only be the beginning. My sense, as a somewhat interested observer, is that the year 2010 is going to see radical change in the way books are sold. The catalyst, I suspect, is this month’s announcement of half a dozen new handheld electronic reading devices. Apple’s Ipad tablet is the most famous, but the Consumer Electronics Show at the beginning of January saw the announcement of the Skiff Reader, Plastic Logic’s Que Pro Reader, Entourage’s Edge, and Spring Design’s Alex. Not all of these are likely to make it to market, but those that do will be competing there with Sony’s Reader, Amazon’s Kindle, and Barnes & Noble’s Nook. Google seems to be planning to sell e-books soon. In other words, a large number of capitalists have been betting, lately, that increasing numbers of people want to read e-books.

Let’s leave to one side, for the duration of this blog post, the question of whether it is wise for our society to spend colossal sums of money replacing an existing technology that is durable, versatile, and aesthetically pleasing. (I will let slip this much: No, I do not care how many trees die. They should be so lucky as to be reincarnated as, say, the poems of Surrey. Ents, do you worst!) Assume, for the sake of argument, that a preponderance of these capitalists will prove lucky in their bets, and that a lot of people are going to buy these devices. That suggests, as I wrote in passing in a recent review of Adrian Johns’s new history of intellectual piracy, that a lot of people will soon be roving the internet in search of free or cheap electronically available texts.

Until recently, books have not suffered from internet-assisted piracy the way that music or film has. That’s mostly because it’s easy to make a digital copy of a CD; you slip it into a slot on the side of your computer and click Import. Making a digital copy of a physical book, on the other hand, is cumbersome, as a book pirate recently confessed to the blog The Millions. At the very least you have to turn all the pages. To do it elegantly, you even have to volunteer your services as a proofreader, which is not very many people’s idea of fun, and I say that as someone who has done his share.

But if publishers themselves are selling digital versions of their books, and all that’s needed to liberate them is a little hacking, the calculus changes. Hacking is fun in a way that proofreading is not. Let us pause here and observe a moment of silence for the death of the idea that book pirates, more literary and therefore more moral than their peers, will somehow prove honorable, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. To the contrary, the pirate interviewed by the Millions said that he deliberately avoided stealing the works of the most successful authors, because they can afford lawyers. Instead he limits his purloining to the work of less commercial writers, such as John Barth, whom he calls “someone who no longer sells very well, I imagine.” Such nobility! “From those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.” If electronic reading devices catch on, the threat of piracy to book publishers—and to authors, at all income levels—is very real.

Of course, large swaths of the publishing industry have not waited for pirates in order to be undone. Since the earliest days of the world wide web, newspapers and magazines have pillaged themselves, giving their articles away for free in pursuit of larger audience share. This is now widely understood to have been a mistake. Newspapers like the Times have many more readers online than they ever had in print, but even with these greater numbers, online ads bring in tiny sums compared to print ads. And online readers pay nothing. In the journalistic world that I happen to inhabit, much of the excitement about Apple’s new device has been driven by a hope that it will offer a chance to press the reset button. People stole MP3s, but they buy ring tones. They downloaded software for free, but they buy apps. Perhaps, publishers hope, people will prove willing to buy newspaper subscriptions on their Apple tablets, even though they’ve never been willing to pay to read them in their desktop browsers. (Long Island’s Newsday recently revealed that three months after putting its website behind a pay wall, only thirty-five people have purchased subscriptions.) Thus a week before Apple announced its tablet, the Times announced that by next year, it will be charging its online readers. Will the new business model work? Will newspapers be saved? Who knows, but there isn’t much to lose by trying. In the weeks before Apple’s announcement, I found myself muttering, in an echo of a recent, very bad movie trailer, “Unleash the Kraken.” We might as well find out what the Kraken will do. At the very least, if it finishes the print media off, we will be spared having to listen to further hectoring sermons from internet triumphalists.

Which reminds me that I’ve strayed from my topic: Amazon. Book publishers, unlike newspaper publishers, still have a lot to lose. About nine months ago, I received an email alert from a friend whose excellent book of nonfiction had just been published and who had discovered, to his dismay, that it was accruing one-star reviews on Amazon, not because readers disliked his book but because they objected that its Kindle price was only a few dollars less than its hardcover price. (The anti-Kindle-price reviews appeared on the webpage of both the Kindle and the hardcover version and figured into his book’s combined star rating.) He was caught in the crossfire of an early skirmish of the war that went nuclear this weekend. Eventually the Kindle price of his book was lowered, though I don’t know who blinked. I remember thinking at the time that the one-star ratings were a bad sign, because they suggested that Amazon had in a way already won the dispute over e-book pricing. Consumers already felt that e-books ought to be no more than ten dollars, and felt it with so much indignation and righteousness that they were willing to punish the very author they wanted to read, if they thought he was charging such sums. (My friend, of course, had no control over the pricing of any of the versions of his book.)

Consumers had come to feel that way largely because Amazon had trained them to, by keeping the prices of nearly all its e-books below ten dollars. Though few consumers understood it then, and probably few still understand it today, Amazon did so by sacrificing heaps and heaps of cash. Most publishers have until now sold their e-books to Amazon for the same wholesale price that they sell their hardcovers—roughly half the hardcover’s list price. It is up to a retailer like Amazon whether to sell the book to consumers at its list price, as printed on the inside front flap, or at a discount. With e-books, Amazon has usually offered a discount so low that it actually loses money. That is, Amazon buys for $12 an e-book whose hardcover list price is $24.95, and then Amazon sells the e-book to its customers for $9.95.

Why would Amazon want to do such a thing? When Amazon first introduced its Kindle reading device, the reception was tepid. But Amazon improved the device in later models, and thanks to its aggressive low pricing on e-books, it now reports that the Kindle and e-books are selling briskly. In other words, with the money that it has lost by discounting e-books, Amazon has bought market share for its e-book reader and for itself as an e-book retailer. To put it still another way, Amazon sped up the American public’s adoption of e-books by unilaterally lowering the American public’s idea of what the natural price of an e-book should be. The outrage of the Amazon customers who punished my friend with one-star reviews, and the outrage of commenters siding with Amazon on the New York Times blog post this weekend about the Macmillan-vs.-Amazon dispute, suggest that it may be too late for publishers like Macmillan to alter that idea.

Newspapers have no one to blame but themselves for having taught the public that they have a right to read newspapers online for free. Publishers, on the other hand, have woken up to the unpleasant discovery that the value of their work is being cheapened in the public mind by a third party: Amazon.

Some consumers have objected that e-books must be cheaper to make than ink-on-paper books. A simple cost breakdown by Money magazine last year, however, suggested that only about 10 percent of a book’s list price goes to printing. But ink-on-paper books have to be shipped, stored, and (when they go unsold) returned, and e-books would be spared these costs, too, as this analysis suggests. Also, according to TBI Research, because e-books are likely to end up with a lower list price after the dust clears, author royalties, calculated as a percentage of the list price, are likely to be lower, too—additional savings! Yay! When all these savings are added up, do you succeed in dropping a list price of $28 to one of $9.95? That’s a big drop. Profit margins at book publishers now are rumored to be no more than 10 percent, where they exist at all. It may not be possible for a single company to publish e-books at that price and also retain the infrastructure necessary to publish ink-on-paper books.

To return to the dispute of the moment: Macmillan has probably been selling its e-books to Amazon at the wholesale price of about $12, and Amazon has been selling them retail for about $10. Macmillan says that it would like to sell its e-books at the wholesale price of about $10.45, and have Amazon sell them for the retail price of $14.95. In other words, Macmillan was offering to earn $2 less per e-book. Amazon, however, insisted that it would prefer to take a $2 loss on each e-book, instead, and became so indignant over the matter that it has now ceased selling any Macmillan titles, print or electronic. Macmillan’s proposal is known as the “agency model” for e-book pricing, and the company probably only dared attempt it because Apple has promised that it will sell e-books for its new tablet on exactly those terms. (Amazon has said that they’re willing to accept the agency model, starting in June, but only if an e-book’s list price does not exceed $9.99.)

As I said at the beginning, my sympathies in this dispute are with Macmillan. Why shouldn’t a book publisher be able to exercise some control over their product’s price? Apple, to choose a wild example, rigidly controls the prices at which retailers may sell its products, and as Paul Collins noted in 2007, the legal barriers to publishers’ exercise of such control no longer exist. Here, alas, is where the pirates come in again. Pirates don’t bother when legal copies are available cheaply and easily. What’s perhaps most breathtaking about the Amazon-Macmillan dispute is how little, finally, is at stake: should the highest price of an e-book be $9.95 or $14.95? No one dreams any more that it’s going to be $28. What’s being fought over is control, and the reason control is being fought over so viciously is that the only way such massive cost savings are going to be achieved is by consolidation—by collapsing a few of the intermediary steps somewhere between the creation of a book and the reading of it. Will you some day download your e-books directly from Farrar, Strauss & Giroux’s website? Will Amazon some day be the publisher of Jonathan Franzen’s novels? Some future between these two outcomes is more likely to happen, but precisely where the division will fall remains to be seen. Authors, in the meantime, had better ask their agents to negotiate their e-book royalties very carefully, seeing as how, while the titans rage, the financial analysts have already factored into their bottom lines the expectation that someone else will be eating our slice of the pie.

Copywrongs

“Terms of Infringement,” my review of Adrian Johns’s new history Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates, appears in this weekend’s issue of The National (Abu Dhabi).

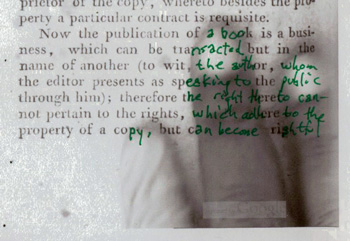

In the opening paragraph of my review, I refer to an essay by Immanuel Kant. Its title is “Of the Injustice of Counterfeiting Books,” and in Google Books, you can see a Google technician’s hand obscuring the text of it at the bottom of page 234. Above: My scan of a print-out, corrected by me in green ink, of Kant’s essay as scanned by Google, along the scanning technician’s hand.

Moral rights vs. work-for-hire

Responding to my post about the Google Book Settlement, a commenter mentioned that he hadn’t claimed his translations because he had done them as work-for-hire, and it occurs to me that the way work-for-hire contracts will play out in the settlement is worth another few words.

In Britain and in Europe, authors own not only a copyright in their works but also moral rights to them. The idea of moral rights is an attempt to address the fact that works of art are not like, say, eggs or lumps of coal. The creator of a work of art cares about what happens to it, even after he’s sold the right to publish it or display it or even own it, in a way that a keeper of chickens does not care about the fate of eggs, or a miner about the fate of coal. Unlike monetary rights, the moral rights to a work of art cannot be transferred.

American law does not similarly protect the moral rights of its authors. In fact, it has a legal convention called “work-for-hire” that is to moral rights what peonage is to citizenship. If you sign a contract with a “work-for-hire” clause, you agree that what you’ve written is a thing without any more integrity than a lump of coal, and that the purchaser can do whatever he wants to it, editorially, without any need to consult you, and that no matter how much or under what circumstances the work is republished, you have no rights to demand further payment. In my opinion, work-for-hire contracts are disreputable acts of force majeure on the part of publishers. Nonetheless, it is almost impossible for a novice writer to avoid signing them, and in the last few years, it has been difficult even for established writers to avoid them. To its shame, the New York Times insists that its freelance writers, including book reviewers, sign work-for-hire contracts, and even The New Yorker insists that shorter pieces like Talk of the Town essays and capsule reviews be works for hire.

But do you really lose rights forever in work because you signed a work-for-hire clause? Let me offer two counterexamples. More than a decade ago, I translated three pieces of Czech fiction for Catbird Press, which were published in an anthology titled Daylight in Nightclub Inferno. I don’t remember whether my translation contract stipulated that it was work for hire; such terms are common with translations, alas, but the publisher of the press, Robert Wechsler, cared deeply about translation, so the contract might have been more generous. In any case, the book went out of print some years ago, and Catbird Press went out of business some time after that. As far as I know, the rights to the anthology were never sold to anyone before or after the press was shut down; certainly no new edition has appeared. So who owns the rights to my translations? Obviously the original authors own the rights to the underlying works of fiction. But the rights to the translations, I would argue, have reverted to me. Let me put it this way: no reputable publisher would try to reissue the book without negotiating some kind of arrangement with the authors and the translators, if they could be located. If they did, I would sic my agent on them in a New York minute. So I have placed a claim on the “inserts” in these books that correspond to my translations.

A second, perhaps more important example. I’ve published a number of short pieces of fiction over the years, but I’ve decided, in my own mind, that my work as a fiction writer officially begins with a novella that I published in the winter 2008 issue of the journal n+1. I’m not going to go from library to library ripping pages out of old journals and anthologies in order to erase my past, but I’ve nonetheless decided that the novella “Sweet Grafton” is opus 1, number 1, and that what came before should be quietly left behind to rot. Lately, though, I have begun to catch glimpses of earlier pieces of my fiction in the Google archive, digitized but not yet released to the public. I don’t care about the money Google might make and withhold from me; I don’t think there’s any serious money to be made. But I don’t want these pieces suddenly to become readily available. Did I sign away my control to these works, with work-for-hire contracts? Again, I don’t remember, and again, I’d argue that it doesn’t matter whether I did. Because even though American law doesn’t respect an author’s moral rights, the community of American publishing heretofore mostly has respected the most important among them. If Saul Bellow had mistakenly signed a work-for-hire contract on an early short story, would anyone have dared reprint it without his permission, or over his protests? No, they wouldn’t have, because by doing so, such a publisher would call down upon himself the opprobrium of not only Bellow but all other writers who are careful about their presentation of their work—which is to say, all other writers that any reputable publisher might want to sign up. Google isn’t part of that community, so it may not be subject to that kind of moral discouragement. And therefore I think this new settlement ought to allow authors to enforce some of their moral rights, whether or not the contract contained a work-for-hire clause. To get started as a writer, I was willing to write almost anything, sometimes under the most absurd terms, and Google is welcome to much of it without any interference from me. But what has my name on it, and took some of my artistry, even where the artistry didn’t succed, I want to retain at least a veto over.

Why not ask for more?

A couple of days ago, in a successful attempt to sabotage my own efforts to meet a deadline, I decided to look into the Google Book Settlement. The settlement is an agreement, hammered out last fall between Google and the Authors Guild, about how Google will share with authors some of the money it hopes to make from its digitization of books in copyright. The agreement itself is very long (you can download it here) and rather complicated. It isn't set in stone quite yet, but the cement is hardening. In order to opt out, you have to notify the settlement administrator by 5 May 2009. You can also stay in the settlement but object to some of its terms, if you make your objections by 5 May 2009. That's only a few months away, so it's not too early to start forming an opinion.

I haven't yet read the agreement all the way through. I didn't think I was going to need to, because I have warm, fuzzy feelings both about Google and the Authors Guild. Also, the site that the settlement administrator has set up for authors to claim their work looks streamlined and friendly and is in fact very easy to use. But now that I've used it, I have some questions, and I'm not sure how to answer them.

For one thing, I'm pretty sure that I filled out the online claims form "wrong," but I felt that I had little choice if I wanted to protect my rights. Then again, I may not have filled them out "wrong"; I'm not sure. Here are some of the dilemmas I found myself facing.

First, under the terms of the settlement, I allegedly don't have rights to my published work unless it was registered with the U.S. Copyright Office. The settlement's fine print claims that this is in conformity with a court decision. I don't think this fine print matters much in my case, because I suspect that most of my published work was copyrighted on my behalf by my publishers, but if it did matter, it would be more than a little enraging. When I started life as a writer, the law of the land rendered it unnecessary to register one's work with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to own copyright in it. In fact, the consensus was that only fussbudgets bothered to. Copyright of one's expression was a common-law claim that didn't need bureaucratic imprimatur; if challenged, you only needed to be able to prove that you and no one else had written the words in question. Listed in Google's database, though not yet digitized, is my undergraduate thesis on Nelson Algren. I know I never registered the copyright. I'm also fairly sure that there are only two surviving copies of it, one on my bookshelf here at home and another in the bowels of Widener Library at Harvard. But it's nonetheless distressing to imagine that if Google were to digitize it, I might not be able to control what happened to it, or make money off it if suddenly a great number of people wanted to know what I thought about Chicago realism when I was twenty. I've also never registered the copyright to any of my magazine articles, ever, but I've felt confident until this week that I owned copyright in them nonetheless, and continued to own copyright when they were reprinted in books, and would not lose that copyright if someone scanned and uploaded it.

Another problem is the settlement's division of the literary world into books and "inserts." An "insert," in the terms of the settlement, is a part of a book that an author owns a right to. For example, the introduction and notes to the Modern Library edition of Royall Tyler's Algerine Captive are copyrighted in my name, so they're my "inserts" in that edition. Since the book is still in print, I told Google that Modern Library still has the rights, and I presume this means the Modern Library will get the lump-sum cash payment for its digitization, not me. But an article that I wrote on Milan Kundera for the magazine Lingua Franca was reprinted in the anthology Quick Studies, which is now out of print, so presumably I will get some money off of that. Not as much as I think I deserve, though. Google is offering to reimburse authors in several ways: first through lump-sum payments for digitization, and later through revenue sharing, based on the money Google makes by selling subscriptions to its database to libraries and colleges, by placing ads on webpages that display the digitized material, and perhaps by selling downloads of books otherwise out of print. As an insert, my old Lingua Franca article will bring me a $15 lump-sum payment and later, perhaps, a $50 payment for inclusion in databases that Google sells to libraries and colleges. But according to Attachment C of the settlement agreement, my insert will bring me nothing from any of Google's other revenue-sharing programs. If Google sells ads next to my Kundera article, or sells someone a download of it, I get zilch. Since Quick Studies is an anthology, it consists entirely of inserts. So who's this revenue going to be shared with? The magazine Lingua Franca, by the way, is defunct. As a writer, I've made far more money off of magazine articles than books at this stage of my career, and I still make money off the reprinting of some of them. It seems to me that excluding "inserts" from substantial revenue sharing is an element of the settlement agreement worth objecting to.

A confusing element of the system: multiple digitized versions. Google's database seems to know that it has scanned both the hardcover and the paperback versions of a short story collection that I helped to translate, Josef Skvorecky's The Tenor Saxophonist's Story. I claimed inserts in both versions, even though the instructions told me not to, because I figured Google would be able to figure out that they were the same book. I claimed both of them for a reason: how else am I to be be sure that Google knows that I have a rights claim (in this case, as a translator, a pretty limited rights claim, but still, something) to both versions? For some reason, Google has scanned two versions of my book American Sympathy, and its database doesn't seem to know they're the same book. Moreover, it also has a reference to what seems to be a free-standing copy of one of my book's chapters, not yet digitized, which I never published separately. I claimed that, too. And I claimed an "insert" in a scholarly anthology that reprints a journal article that overlaps a great deal with one of the book's chapters. I know for a fact that no one else has any right to that insert. Google's instructions say that if an insert reprints material also published in a book, the author should only claim either the book or the insert, but not both. Well, that makes sense as far as the lump payments go. But if Google is later going to sell ads on webpages or sell downloads, it doesn't make sense. The income that Google will be making off my content will be split between the various versions of my work that are in its databases, and I should be able to claim revenue from all versions they hold of everything I've written. (By the way, this book, too, remains in print, so as I understand it, I won't be getting any lump-sum payments for it no matter how I fill out the forms.)

I'll end by saying that this agreement is so complex that it seems destined to have unintended consequences, and that I welcome corrections to any misunderstandings I may have made here. I look forward to learning other writers' reactions to the agreement and the claims process, because my sense is that most of us in the rank and file have yet to weigh in on them.