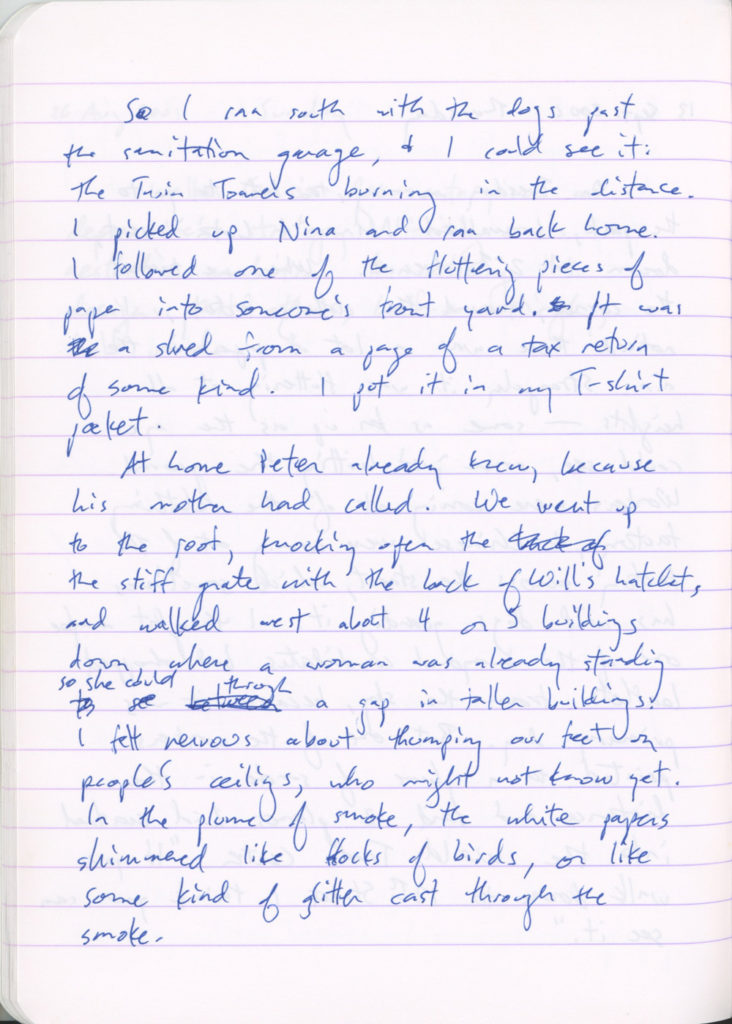

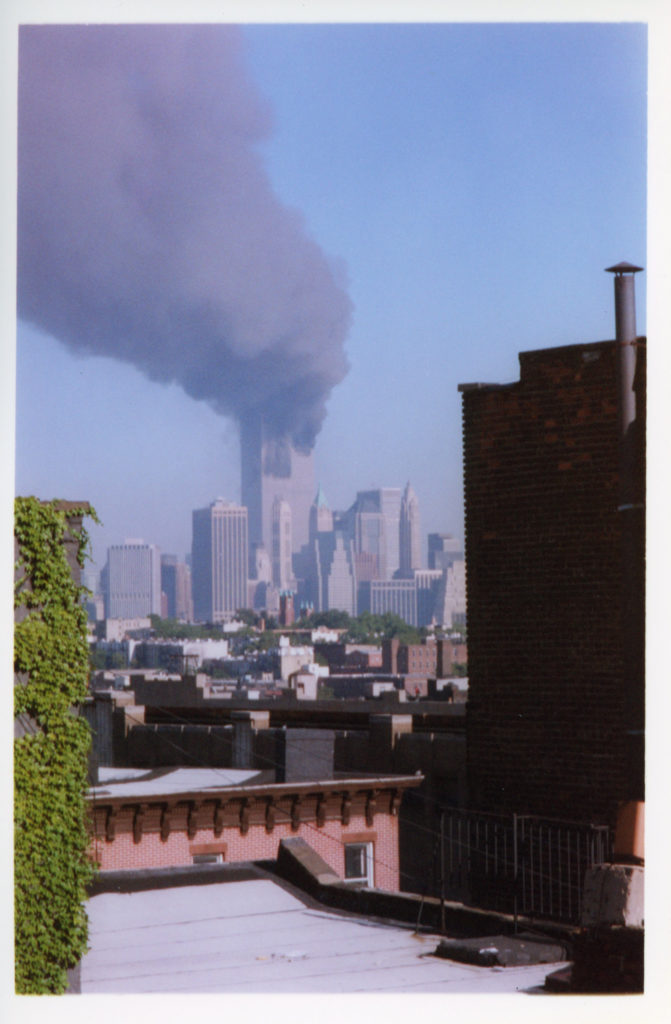

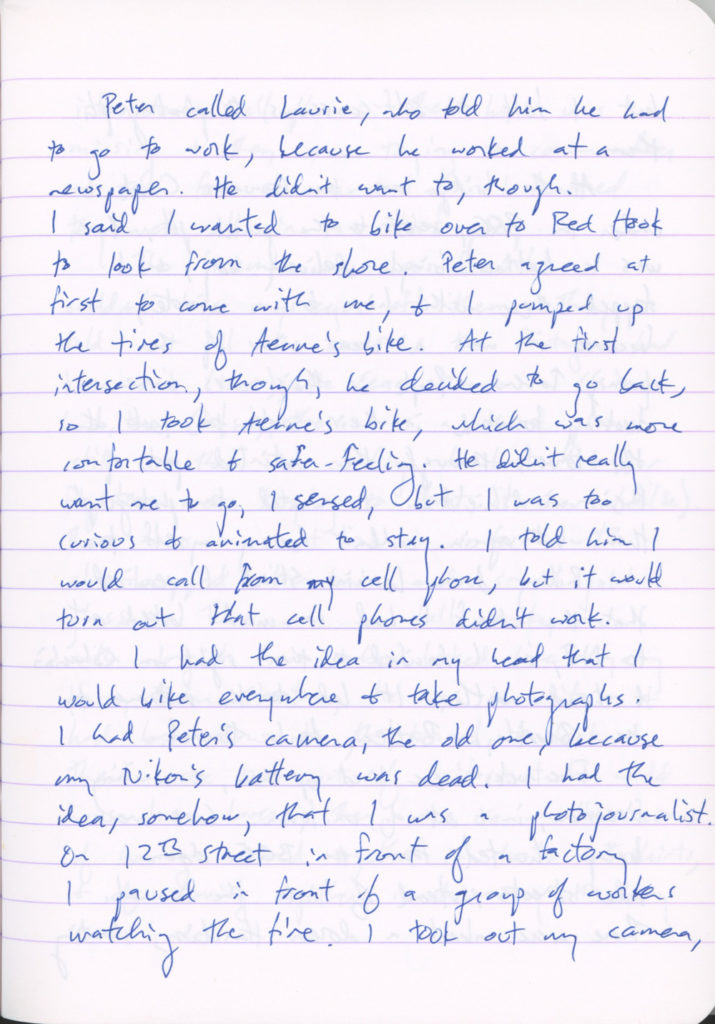

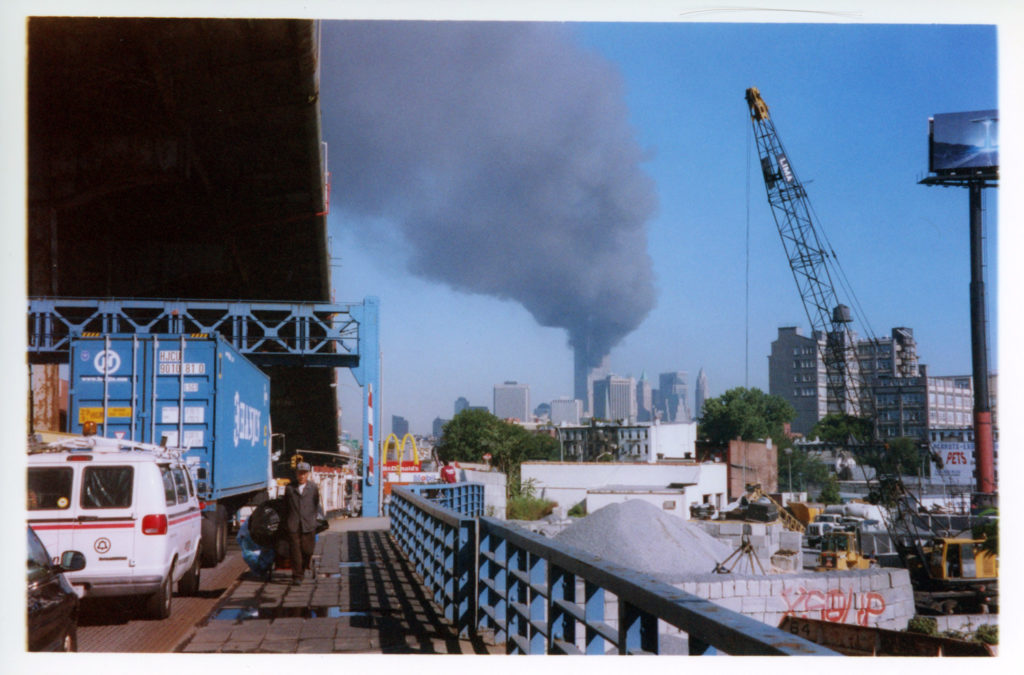

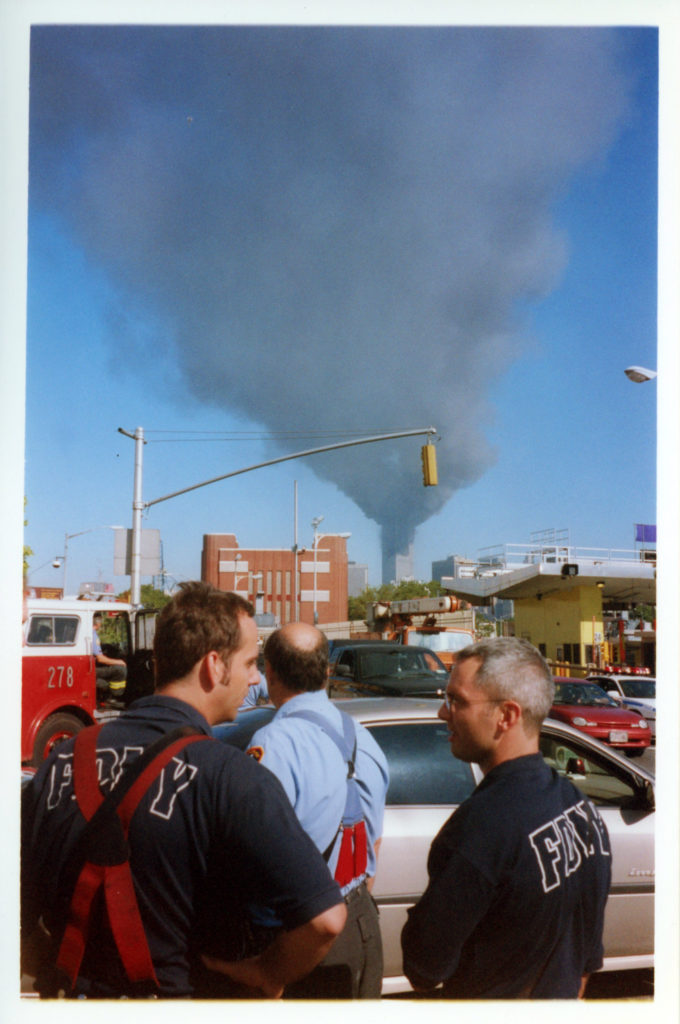

Here’s an entry I made in my journal on 13 September 2001. At the time, Peter and I were living on 11th Street near Fourth Avenue, in Brooklyn. Lota was our black Lab mix, and Nina was my sister’s chihuahua, whom we were dog-sitting. I’m including scans of some photos I took that day as well, which get mentioned in the journal. Hope you can read my handwriting.

I didn’t write more later; I didn’t write any journal entries for the next three months. I don’t remember the rest of September 11 anywhere near as clearly as the part that I wrote down, but I do know that I biked into Manhattan that afternoon with Lydia, a friend of friends who either was, or was about to be, a medical student, and wanted to see if she could volunteer. I took a different camera with me on that ride, and took more photos, including the one of the sun at the top of this post and the ones of Manhattan below.