Peter and I are trying to revive an old practice, reading a poem together when we get up in the morning. The first one in the anthology we’ve chosen is “Beeny Cliff,” by Thomas Hardy, about a seaside rock face in Cornwall that Hardy visited with his first wife, Emma Lavinia Gifford, soon after they met. The poem starts by invoking the colors they saw in the ocean:

The poem’s subtitle is “March 1870—March 1913,” which are the month Hardy met Gifford and the month he revisited the site, forty-three years later, after her death. The first stanza has no tense, however; it merely apostrophizes the colors and then Gifford in a voice that belongs to neither the present nor the past, a voice that floats between.

The woman whom I loved so, and who loyally loved me.

In a memoir that Gifford wrote not long before she died, and which Hardy didn’t discover until after, she recalls that when she rode her pony, which was named Fanny, “Fanny and I were one creature, and very happy,” and that she rode him in a brown dress whose color matched his coat, so long that she had to carry the end of it in order not to trip. She met Hardy because he was the architect hired to remodel the church where her brother-in-law was rector, a structure so dilapidated that “birds and bats had a good time” in the roof timbers. She remembered that when the architect visited, “I rode my pretty mare Fanny and he walked by my side, and I showed him some of the neighbourhood—the cliffs, along the roads, and through the scattered hamlets, sometimes gazing down at the solemn small shores below, where the seals lived, coming out of great deep caverns very occasionally.” In her biography of Hardy, Claire Tomalin reports that Gifford and Hardy sketched each other, the Victorian equivalent of taking joint selfies.

Unlike the poem’s first stanza, the second commits itself to the past, and describes one of the couple’s outings.

In a nether sky, engrossed in saying their ceaseless babbling say,

As we laughed light-heartedly aloft on that clear-sunned March day.

Peter and I both stumbled over “mews,” which are gulls, it turns out, not stables. I thought at first that “plained” had something to do with the flatness of the horizon, but Hardy means “cried” (as in the related words “complained” and “plaintive”). Gulls are crying below, in other words, but “mews plained” comes a little closer to the sound gulls make when they’re doing so. Hardy doesn’t mind using a word that’s a step removed from common diction if he can gain a poetic effect by it. His calling the sea below “a nether sky” is a nifty metaphor, because sea and sky are alike in both stretching away into the distance, where they meet and mirror each other along the horizon, and the metaphor accomplishes a neat trick of perspective: looking down somehow feels like looking up. There’s a suggestion, too, that the sea, or the reversed sky, covers an underworld, a suggestion at the moment easy to dismiss, given that the sea is distant and the murmuring of its waves sounds trivial, easily interrupted by the laughter he and Gifford are sharing.

And the Atlantic dyed its levels with a dull misfeatured stain,

And then the sun burst out again, and purples prinked the main.

Colors are always subtle in Hardy. “Irised” means “iridescent,” the shimmer of rainbow that sometimes appears in rain, especially when seen from above. The Atlantic Ocean, lying behind this prismatic rain, appears to color it, to darken it, in horizontal strata. Hardy’s language here is as precise and general as an experiment in optics. At one moment he sounds like he’s talking to you in a conversational tone—“A little cloud then cloaked us”—and in the next line, he compresses his thought to the density of a mathematical formula. “Irised” isn’t a common word, but its meaning is clear, and its compactness keeps the poem in its trotting rhythm. There’s a kind of grammatical insistence, too, I think, in the accumulation of past participles—“engrossed,” “sunned,” “irised,” “misfeatured.” There’s even one at the core of “light-heartedly.” Act is being consolidated into completed action. In the “dull misfeatured stain” the malevolence of the “nether sky” is again visible, still in the background for now but beginning to leach through. Happily the sun returns—the action of this stanza is taking place in the past, when rebirths were still possible—and transfigures the staining ocean, whose tints now become decoration.

And shall she and I not go there once again now March is nigh,

And the sweet things said in that March say anew there by and by?

With the em-dash, Hardy jump-cuts to the present. Beeny has become “old Beeny,” fond in memory, and Hardy asks, as if challenging a limit he knows he can’t pass, whether he and Gifford will ever visit it again together. The small love talk he exchanged with her on the cliff summit years ago now seems as distant as the babbling of the waves did when he stood next to her there.

The woman now is—elsewhere—whom the ambling pony bore,

And nor knows nor cares for Beeny, and will laugh there nevermore.

The phrase “chasmal beauty” and the name “Beeny” are repeated, as if to stress that the cliff still exists, as the “woman” (a word repeated with a similar stress in the first stanza) does not. In any sublime geographic feature, there’s a hint of eternity, which is part of the attraction for human visitors, a hint that plays on the visitors a very slow joke, in that while rocks and sea may be lasting, any admirers, though they may feel like they have been placed above nature by virtue of their powers of perception, are not.

In his two-volume autobiography, written and then posthumously published under the not very convincing pretense that his second wife was the author of it, Hardy reprinted some of the notes he made in his journal when he first visited Beeny Cliff in March 1870 with Gifford.

March 10. Went with E. L. G. to Beeny Cliff. She on horseback. . . . On the cliff. . . . ‘The tender grace of a day,’ etc. The run down to the edge. The coming home.

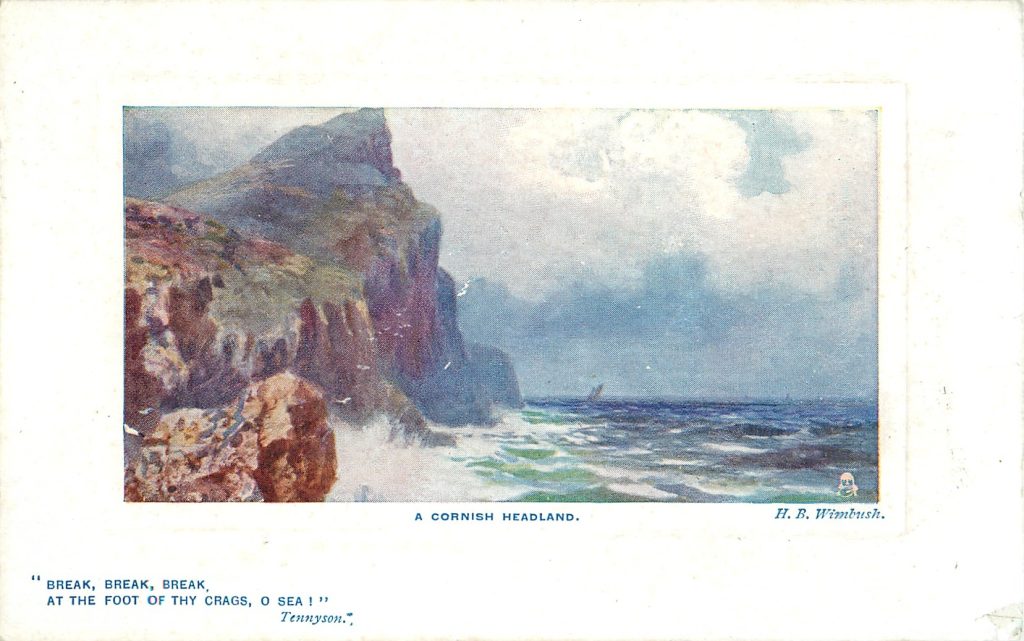

The ellipses are Hardy’s. What a little shocked me, when an annotation to “Beeny Cliff” sent me to Hardy’s autobiography for a look at this journal entry, is the quoted fragment of poetry: “The tender grace of a day.” It comes from the conclusion of Tennyson’s poem “Break, break, break,” which is also about looking out over the sea while in mourning. The last two lines of that poem read as follows:

Will never come back to me.

Tennyson wrote the poem while grieving for his young friend Arthur Hallam, who had died while abroad, and whose death became the subject of his later masterpiece, In Memoriam, which imaginatively follows the homeward progress by sea of Hallam’s sealed coffin. What’s puzzling is that while it makes a great deal of sense for “Break, break, break” to have been in Hardy’s mind in 1913, when he was composing “Beeny Cliff” as an elegy for Gifford, the poem seems to have been in his mind already in 1870, back when he was courting her. The stenographic style of the journal entry implies that when he was writing about the day, he was confident he would always remember its texture. “The run down to the edge. The coming home.” These were lyrical moments that he knew a brief prompt would always return him to, the way a short quoted phrase can call to mind the poem it has dropped out of. Did he and Gifford kiss when they came to the edge of the cliff? Did the sight of the waves crashing below bring the same Tennyson poem into both of their minds (“Break, break, break / On thy cold gray stones, O Sea!”), and did one of them quote it to the other? Those details are not recoverable by us now, but the surprise is that the nether sky that Hardy saw in the sea that day, with Gifford by his side, was not a later invention, projected onto the past by a grieving husband. He saw it then, and so, probably, did she. “The tender grace of a day that is dead”: the young lovers wouldn’t have quoted that Tennyson line to each other unless they were already aware that they were living through a moment that was not going to return, aware that the beauty of their happiness together was not going to last as long as Beeny Cliff.