What was Melville’s mission statement? Issue #2 of my newsletter.

Missions

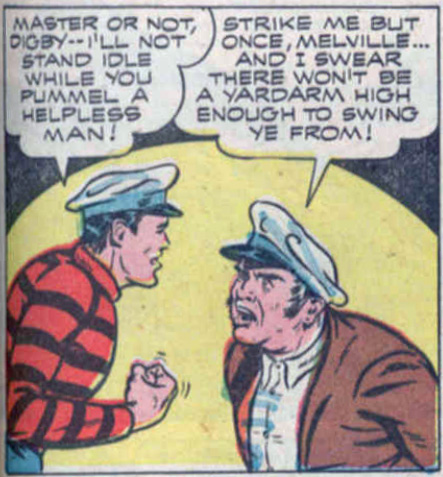

A few days ago a friend sent me a link to “Sea Scrivener,” a 1944 comic-book biography of Herman Melville:

A little Billy Budd seems to have gotten mixed into the life (which starts on page 63, on the website linked to). While in grad school, I made a pilgrimage to Melville’s grave in Woodlawn cemetery in the Bronx, where a blank scroll decorates his headstone. My recollection is that on my way to the grave, I walked past an obelisk commemorating a family named Budd. Had it been put there before or after Melville? The New York Times reports that “plots are still available in the vicinity of Herman Melville, with prices starting at $20,000.” I’ve been getting a fair amount of junk mail from cemeteries lately, which causes one to wonder what the algorithms know about one. If any were to advertise such a propinquity, the solicitation would be a little more tempting.

At a recent dinner party, a friend who works in branding explained the importance of mission statements. Nike, for example, aims “to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world,” whereas its rivals just hope to make running shoes. The ad executive who came up with Nike’s tagline “Just do it,” by the way, was inspired by the end of murderer Gary Gilmore’s life. As Norman Mailer recounts, in The Executioner’s Song:

Then the Warden said, “Do you have anything you’d like to say?” and Gary looked up at the ceiling and hesitated, then said, “Let’s do it.”

At first, wondering whether writers have, or should have, mission statements struck me as just intellectual recreation, and maybe a little bit philistine in an amiable way. But as it happens, I worry constantly that my career is a magpie’s nest—I’ve written about antebellum legal flotsam, pirates, gay history, voting ethics, plus a couple of novels, and some commentary on sci-fi movies—and what if, all along, without my knowing it, I’ve been coherent? What a consolation that would be. All I need to do is discover the secret unity beneath my motley. The night after the dinner party, therefore, I couldn’t sleep for trying to deduce the missions of writers, retrospectively. Plato: to write down a conversation with someone who loves wisdom for its own sake. Melville: to penetrate the mystery of being incarnated as a man in a capitalist world. Orwell: to try to tell the truth about people even in the face of their dislike of hearing it. Margaret Fuller: to further the progress of liberty through intellectual service, while a woman in the 19th century. Emerson: to dramatize the way spirit escapes from and is betrayed by the forms that aim to represent it.

I couldn’t figure out my own. Something to do with the connection and conflict between life and art, between attachment and detachment? Which doesn’t explain why last year I wrote an essay about finance capitalism. Maybe the common element is my interest in stories that depose the individual they purport to serve? It would be pleasant to have some reason to think that it wasn’t just out of distractibility that I was a critic and journalist before I got around to becoming a novelist, and to know whether my fiction has to be about gay people or just happens to be about them.

“Journalism is the art of coming too late as early as possible.” —Stig Dagerman, quoted in Johannes Lichtman’s new novel Such Good Work. I like Lichtman’s gentle sense of humor. He’s very good at, for example, suggesting how bad Germans are at explaining card games: “When you put down a queen and then he puts down a queen, then two are down, so it’s until the next turn, unless it is broken.” Such Good Work is about a recent MFA grad who tries to distract himself from relapsing into opiate addiction by moving to Sweden, where he further distracts himself by volunteering to teach refugee children. It turns into a meditation on distraction and ambition, and whether feeling good undermines attempts at doing good, and ends up suggesting, without getting too heavy-handed, that there may not be a higher purpose than helping other people and oneself pass the time not unhappily.

By a stroke of luck, Peter and I were recently able to see The Fabulous Nicholas Brothers, a one-night-only presentation at BAM by Film Forum programming director Bruce Goldstein of dance numbers by, home movies of, and interviews with Fayard and Harold Nicholas, debonair black dancers in American movies of the 1930s and 1940s. (An earlier version of Goldstein’s presentation seems to be available here. We were clued in about the Nicholas Brothers because, a couple of months ago, while Peter was reading Zadie Smith, he was so struck by her praise of their dance number in the 1943 movie Stormy Weather that we watched it online.) By the end of Goldstein’s presentation, during a video he and a collaborator had shot of the brothers reprising, in their seventies, a dance number that they had first recorded for Vitaphone in their teens, I was in tears—at their elegance, at their good nature, at the longevity of hard work and talent. In Goldstein’s telling, they took every opportunity that was consonant with dignity, with a cheerfulness that seems to have been a force of nature. If there were frustrations and disagreements, they seem not to have dwelt on them, and if there were romantic troubles or personality clashes, they did as well as they could and moved on. Nothing became a tragedy; no setback was allowed to become as meaningful as the work. There’s something beautiful about that, and about their gameness—their willingness always to do their best. Were they lucky? Yes, probably, Goldstein’s documentary work suggests: in having been loved since childhood, in having been gifted, in having boundless enthusiasm. But because they were black they weren’t as famous or as successful as they should have been, and they seem neither to have pretended not to see this nor to have let it eat away at their love for their art. A model.

This is issue #2 of Leaflet, a newsletter by Caleb Crain. My next novel comes out in August, and you can buy an early copy now from your local bookstore, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.