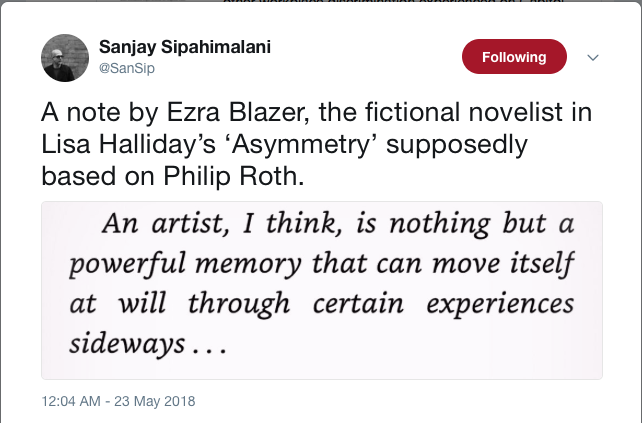

In the aftermath of Philip Roth’s death, a sentence that appeared in Lisa Halliday’s novel Asymmetry, which fictionalizes Halliday’s friendship with Roth, has started circulating:

“An artist, I think, is nothing but a powerful memory that can move itself through certain experiences sideways.” It’s a nice sentence—a pleasing mix of elusive and resonant. Did Roth himself write it? Well, no, though he could have transcribed it. Ruth Margalit got its provenance half-right in her recent review of Asymmetry for the New York Review of Books. Margalit claimed that in Halliday’s novel “The quote bears no attribution, but it comes from the nineteenth-century novelist Stephen Crane.”

Not exactly. In fact the quote appears in no novel, poem, or letter that Stephen Crane is known to have written. If you google, you’ll see that it has popped up in essays about Crane and in biographies of him for decades, but its earliest appearance is on page 232 of a 1923 biography of Crane by Thomas Beer. Beer’s biography, however, is largely fictional. Beer snookered not a few—Alfred Kazin and John Berryman are among those who fell for his tales—but as I wrote in a 2014 New Yorker essay about Crane, scholars have known since 1990 “that scores of the letters [in Beer’s biography] were ‘concocted,'” and “more than half a dozen people in Beer’s biography were concocted, too—including many whom Beer had credited as sources.” Beer seems to have been gay—he once commended a novel for containing “the most wonderful description of hair on a boy’s chest,” and in letters he addressed male friends as “Bitch” and “Purple Sunflower”—but he was conflicted about it, and he seems to have had a troubled identification with Crane’s youth, looks, accomplishment, and sexual amorality. Last week, after reading Margalit’s review, I checked the two-volume 1988 edition of Crane’s correspondence, and the scholars who compiled it, Stanley Wertheim and Paul Sorrentino, don’t include the sideways-moving-memory sentence. It doesn’t even appear in the appendix they devoted to letters that have no source apart from Beer’s biography. In Beer’s biography, the sentence is part of a letter that Crane supposedly wrote to a young aspiring writer, and the letter jabs at Henry James and André Gide, which makes it easy to look for in the index to Wertheim and Sorrentino’s edition. (In his ventriloquisms, Beer liked to knock other gay writers; it’s his tell.)

In short, neither Philip Roth nor Stephen Crane came up with the idea that an artist is a powerful memory moving itself through experiences sideways. It came instead from a soul who had a much more fraught relationship with his sexuality and his powers of invention.