The National Center for Education Statistics has just released a report on its 2003 survey of adult literacy in America. I’ve been eagerly awaiting it, to see if it would confirm or deny my quasi-apocalyptic anxieties about reading in America. Like the NEA’s 2004 report Reading at Risk, the National Center for Education Statistics’s National Assessment of Adult Literacy gives hard numbers to changes that have taken place in American reading in the last decade. But whereas the NEA was concerned with the reading of literature, the NCES focuses on the skills that go into reading, broadly defined.

The good news is that everyone seems to have gotten better with numbers, or what the NCES calls “quantitative literacy.” And the average scores on “prose literacy” (aka literacy classic—the ability to read a paragraph, understand it, and take issue with it if necessary) and “document literacy” (the ability to interpret maps, prescription labels, and the sides of cereal boxes) have held steady overall. It was therefore my first impression that perhaps I could file my reading anxieties under Apocalypses That Didn’t Arrive, and turn my attention elsewhere, like, say, our Netflix queue, which really needs it.

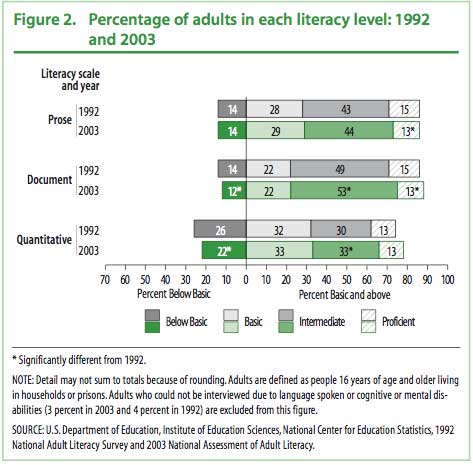

On closer inspection, however, the statistics are not quite so encouraging. To see why, you need to go a bit further into the report, A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century. In figure 2, on page 4, take a look at the change between 1992 and 2003 in the percentage-point breakdown of proficient, intermediate, basic, and below-basic readers.

You’ll notice that the proficient readers of prose have declined from 15% in 1992 to 13% in 2003, and that this result gets an asterisk, because the difference is statistically significant. Something similar happened with document literacy. And quantitative literacy improved overall not because of any increase in the number of people proficient with numbers, but because the number of people below a basic level declined.

Everyone should be as literate as possible in every way, of course. But it’s proficiency in prose literacy that keeps me up nights. That’s the group likely to subscribe to newspapers and to buy books. It’s also the one crucial to a functioning democracy. To explain their division of literacy into three types and four levels, the NCES writers list real-world tasks for each of the twelve type-level combinations. An example of successful basic document literacy: using the TV guide. An example of successful below-basic quantitative literacy: adding up items on a deposit slip at the bank. An example of successful proficient prose literacy: “comparing viewpoints in two editorials.” The share of Americans who can do that has gone down over the past decade, from 15% to 13%. That’s not a good sign. In a mature, industrial democracy, it’s a very peculiar sign. We’re not talking about how much reading Americans do. We’re talking about how many Americans are capable of it. I don’t think you can pin the shift on immigration; whites and Hispanics lost ground, blacks held steady, but Asian and Pacific Islanders gained proficient prose readers.

OK, two more observations, and then I have to go to bed. Page 14 has a real zinger: “Average prose literacy decreased for all levels of education attainment between 1992 and 2003.” Only 40% of college graduates were proficient readers of prose in 1992; only 31% were in 2003. Happily, the number of Americans with college degrees rose by two percentage points in the same period.

And then, finally, you’re wondering why proficient readers of prose are on the decline. The answer is in figure 17, on page 16.

What this chart shows is that it’s still hard to get a job if you have basic or below-basic literacy skills. But it’s not as hard as it once was. In the two sets of columns on the left, for “below basic” and “basic,” the movement is upward, toward employment. On the right, by contrast, those with intermediate or proficient levels of prose literacy have actually slumped down slightly, into unemployment and non-employment. In 1992, a proficient reader was more than twice as likely to have a full-time job as a below-basic reader. In 2003, he was less than twice as likely. In other words, the American labor market rewards literacy less aggressively than it once did.