Over at the Paris Review Daily, I ruminate on Steven Soderbergh’s new movie Contagion.

Category: Film

An introduction to “Paprika”

[The Rubin Museum of Art asked me to introduce the movie Paprika on March 4, 2011, one of a series of dream-themed films that the museum is showing this month. Here's what I had to say.]

Paprika, the movie we're about to see, is based on a fictional technology that allows people to share a dream. In fact, though, such a technology does exist. Several such technologies do: A poem can share a dream. A novel can sustain the sharing of one for weeks or even months. Movies may be the most vivid means of dream-sharing. Their power is acknowledged every time a timid viewer like me says, of a particularly gory or scary-looking one, that he can't go see it because it would give him nightmares.

Suspend your belief in poems, novels, and movies for a moment, however, and imagine that dream-sharing is something completely new in the world. How will society react? Will people use the technology to reach a new understanding of themselves, extending the insights of psychoanalysis and philosophy? Such a development would require a great deal of attention to people as individuals. It would probably be easier and more profitable to use the new technology for entertainment. A dream that flatters or pleases dreamers could be mass-distributed. Corporations could hire its distributors to spike it with appetites for products; governments could pay for inducements to passivity or simply for distractions that camouflage what is happening to citizens in the real world. Plato would almost certainly have banned dream sharing from his republic.

In animated movies, and in live-action movies enhanced by computer graphics, the few constraints that everyday physics once imposed on moviemaking are overcome. The takeover of animation by computers, in the last few decades, may have intensified anxieties. What is the fate of creativity in an electronic age? Will it be the handmaiden of liberation or slavery? Like all great artists, Satoshi Kon, the director of Paprika, seems to have harbored a certain ambivalence about his chosen medium. Though computers have made it possible to automate much animation, Kon liked to draw storyboards for his movies himself, by hand, and in none of his movies did he shrink from challenging the conventions of the genre.

Kon seems, in fact, to have seen himself as a little bit at war with the conventions of mass-produced Japanese animation, making them the butt of a joke in the first scene of the first movie he directed. Kon's Perfect Blue, released in 1997, begins with an action sequence by costumed superheroes, set to blaring, triumphant music, but the superheroes are almost immediately revealed to be no more than the mediocre opening act at a rinky-dink outdoor theater. (The joke is reminiscent of the melodramatic action-movie "conclusion" that begins Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels.) Perfect Blue is really about the next act at that rinky-dink theater, an all-girl pop group, and in particular, about the identity crisis that the group's lead singer suffers as she transforms herself from an inoffensive teen idol into an actress with roles that are emotionally painful and sexually mature. Kon imagines the young actress being haunted by her pink-tutu-wearing younger self, and it soon becomes difficult for the viewer to distinguish between the actress's real-world agonies and the imaginary ones that she is portraying in her first movie, whose title is, tellingly, "Double Bind." The transitions between reality and fantasy are dizzying. "The real life images and the virtual images come and go quickly," Kon explained in an interview.

When you are watching the film, you sometimes feel like losing yourself, in whichever world you are watching, real or virtual. But after going back and forth between the real world and the virtual world, you eventually find your own identity through your own powers. Nobody can help you do this. You are ultimately the only person who can truly find a place where you know you belong.

In Kon's second feature film, Millennium Actress, released in 2002, he explored a similar confusion, this time by imagining a documentary about an elderly actress who can no longer tell the difference between memories of her life and memories of the movie roles she played. Her love story hopscotches through a century of Japanese film history and several centuries of Japanese history simultaneously. In his third film, Tokyo Godfathers, released in 2003, he defied convention in his choice of subject matter: three homeless people—an alcoholic man, a transvestite, and a runaway teenage girl—find an abandoned baby while rummaging through garbage on Christmas. Trying to do the right thing by the baby, each character must re-examine a melodramatic fantasy that has taken the place of his true life story.

Paprika, released in 2006, reprises these themes: doubles, the misapprehension of the past, the risk of sexuality, the confusion between reality and fantasy. Kon imagines his movie's dream-sharing technology as a small, bent, white wand, shaped like a question mark or a miniature shepherd's crook, with articulated teeth, the size of grains of rice, that glow a soothing robin's egg blue. The DC Mini, as it's called, is cute and menacing at the same time, like the many handheld devices that one nowadays sees people plugged into on the subway. Its inventor is a childish, absurdly overweight man named Dr. Tokita, whose talent everyone envies. The pioneer in its therapeutic use, however, is a stylish black-haired research psychologist named Dr. Atsuko Chiba, who, since the technology is not yet legal, treats patients only while disguised as red-haired, freckled girl named Paprika.

In the movie Inception, which some of you may have seen, there are clear rules about the mechanics of entering dreams. In Paprika, there aren't. There is a mechanism for awakening dreamers, but its function isn't certain. One can never be certain whose dream one is in; in fact, control of a dream may change from moment to moment. The conceit of Inception is that it takes great cunning and much effort to implant an alien idea into someone's mind. In Paprika, such an implantation is distressingly easy. The difficult thing is to learn through dreams how to become oneself.

Be patient, Paprika several times advises one of her subjects. Much of the movie is devoted to the interpretation of a single dream, with an attention to detail and a willingness to defer understanding that Freud would not have been ashamed of. But not all the dreams in the movie prove susceptible to analysis. In a particularly dangerous one, we seem to see capitalism run amok—commodities themselves on the march, as if toward an Armageddon or a coronation. The philosopher Martin Buber once warned of "the despotism of the proliferating It under which the I, more and more impotent, is still dreaming that it is in command." Will this someday be humanity's only dream?

Kon died of pancreatic cancer in August 2010 at the age of forty-six. A posthumously posted letter to fans suggested that he had completed storyboards for The Dreaming Machine, a children's movie that may be released later this year. One suspects, though, that Paprika is his masterpiece, and his early death makes more poignant the rich dream at the movie's start, in which one hears the slowing clicks of a movie projector that has come too soon to the end of its reel.

Thanks to all of you for coming out to see the movie, and thanks to Tim McHenry and Brendan Hadcock of the Rubin Museum of Art for inviting me and for arranging the screening. Enjoy the greatest showtime.

I’m introducing “Paprika” on Friday at the Rubin Museum

I'm going to be introducing Paprika, Satoshi Kon's anime movie about a team of therapists who have discovered a technology that enables them to enter their patients' dreams, this Friday, March 4, at 9:30pm at the Rubin Museum of Art, 150 West 17th Street (between 6th and 7th Avenues) in Manhattan. $7. (I mentioned the movie in passing last summer, when I wrote about Inception for the Paris Review Daily.) Hope to see you there!

Not being there

Over at the Paris Review Daily, I argue that in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, capital dreams of abusing itself.

Traumdeutung at the movies

Over at the Paris Review, I synthesize my quack science-fiction criticism and my recent reading of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams into a blog post about Christopher Nolan’s new movie Inception.

Left on the cutting-room floor was a comparison between the movie’s diagram of dreaming and Freud’s—too geeky even for the Paris Review, and offered as an outtake here:

As part of a recruiting pitch, the dream invader Cobb, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, draws the following diagram in Christopher Nolan’s new movie Inception:

While the mind is dreaming, Cobb claims, it creates a world and experiences it simultaneously, and the tightness of the feedback loop is what makes dreams so potent and intoxicating.

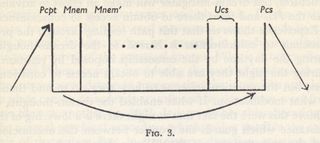

For comparison, here is the diagram that Sigmund Freud drew to explain dreaming:

Read from left to right, Freud’s diagram represents waking life. At the far left, stimuli (sounds, images, tastes, etc.) enter the human mind through the perceptual system, which Freud labels “Pcpt.” Once inside the mind, the perceptions leave a memory trace, labeled “Mnem”—a record of the sensation and of associations between them. Over the course of a lifetime, a person has many experiences and therefore accumulates many layers of memories and associations. Freud suggests these layers by adding a level “Mnem-prime” after “Mnem” and then adding ellipsis dots after that. These memories are for the most part unconscious, though many of them can be made conscious. Also unconscious (“Ucs”) are many of a person’s wishes and fears, some of the most powerful of which are the oldest, which derive from memory traces laid down in childhood, when a person is most impressionable. In responding to a new experience, a person may be motivated by his unconscious but only takes action through his preconscious mind (“Pcs”). It’s the preconscious that brings memories and associations into consciousness and controls motor activity—the downward arrow exiting the diagram on the far right.

In waking life, excitation moves from left to right, in the direction of the arrow that Freud drew along the bottom of his diagram. But in dreams, Freud suggests, excitation moves backward—from right to left. Dreams begin as wishes in the unconscious and move backward through memory until at last they reach the perceptual system, which they stimulate into hallucination.

Freud’s diagram seems at first to lack a loop like the one in Cobb’s, but in fact it does contain one. That’s because the outside world appears both at the far left of Freud’s diagram and at the far right. The world is both the source of sensation and the domain upon which a person acts. In Freud’s understanding, a dream breaks the loop through the outer world, sending excitation into a short circuit that never leaves the mind. Whereas in waking life a person acts upon the world in order to attain remembered pleasures, a dreamer merely hallucinates the satisfaction of his wishes. Freud thinks that infants for a while attempt the same psychic shortcut even while awake. But “the bitter experience of life,” Freud drily notes, forces a child to concede in time that an imaginary bottle of milk is not as good as a real one.