Over at the Paris Review Daily, I ruminate on Steven Soderbergh’s new movie Contagion.

A WTC memory

More than a decade ago, I did a little bit of fear arbitrage. I was facing a very minor bit of surgery, so minor that after the fact it turned out that it hadn’t been necessary at all, though of course I didn’t know that at the time. I had decided that I was going to stay conscious during it, on the general principle that it isn’t a bad idea to keep an eye on a person cutting into you with a knife. Indeed, when the fateful day arrived, I was able to watch the doctor making her incisions, and my curiosity turned out to be more powerful than my squeamishness. (I remembered being especially fascinated by the glistening white layer of fat that lay just beneath my skin, deeper than even the worst scraping of a knee had hitherto revealed. At least I think it was fat.) I knew in advance that thanks to local anesthetics I wasn’t going to feel any pain, but to say that I dreaded the surgery would be an understatement. I hate to go the doctor even for check-ups.

More than a decade ago, I did a little bit of fear arbitrage. I was facing a very minor bit of surgery, so minor that after the fact it turned out that it hadn’t been necessary at all, though of course I didn’t know that at the time. I had decided that I was going to stay conscious during it, on the general principle that it isn’t a bad idea to keep an eye on a person cutting into you with a knife. Indeed, when the fateful day arrived, I was able to watch the doctor making her incisions, and my curiosity turned out to be more powerful than my squeamishness. (I remembered being especially fascinated by the glistening white layer of fat that lay just beneath my skin, deeper than even the worst scraping of a knee had hitherto revealed. At least I think it was fat.) I knew in advance that thanks to local anesthetics I wasn’t going to feel any pain, but to say that I dreaded the surgery would be an understatement. I hate to go the doctor even for check-ups.

Mulling over my fate, I berated myself over my cowardice for days until, in defense against my self-attacks, I started listing things that other people were afraid of that for me held no terrors at all. I had recently seen ads—I no longer remember where, maybe in one of the weekly giveaway newspapers that I used to read at lunch in the local slice joint—for parasailing in New York Harbor. I probably will never have the courage to jump out of a plane, but parasailing didn’t frighten me. By lifting you up into the sky, a parachute-sail proves its ability to keep you up there, or so my mind, surprisingly rational on this point, concluded. If modern medicine had sentenced me to be more brave than I wanted to be about surgery, it only seemed fair for me to reward myself by enjoying a risk that didn’t scare me.

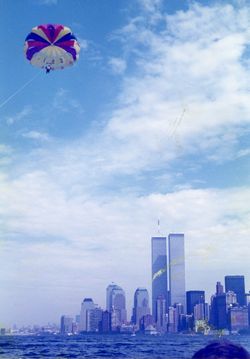

I called an old friend who had survived lung cancer in childhood and had recently started taking multi-day, high-endurance hikes in the West; he was game, too. Across the street from the then-extant World Trade Center, just outside the Winter Garden, where a long quote from Frank O’Hara is carved in marble, we met the two men running the parasailing outfit. They were working-class New Jersey boating guys, a little brusque. I think we paid them cash, but I don’t remember how much—maybe $100 apiece? I remember that it was a lot for a graduate student, but not a lot compared to other New York luxuries. The operators didn’t make any small talk, nor did they offer any marketingesque pleasantries about the adventure we had chosen and how meaningful it might or might not be. They merely nodded to the life jackets, unmoored the boat, and motored out into the harbor with us. In the face of their alpha-male taciturnity, I remember scrutinizing the winch at the back of the vessel for clues about how the whole thing was going to work. For further clues there were only the occasional radio exchanges between our boat and the harbor police, terse and somewhat cryptic, from which I gathered that parasail operators were more tolerated than welcomed by the water authorities, who expected us to wait patiently until more-functional marine traffic had passed. The operators may also have had to clear things with air traffic control, or at least with the nearby helipads—I can’t recall. My friend and I weren’t the only passengers; there was also a man in his early thirties, who seemed to be a financial services type. His wife and elementary-school-age daughter were keeping him company but weren’t going to go up themselves.

It soon became clear that the boating guys hadn’t bothered to explain the parasail procedure to us because there was little for a passenger to do except enjoy the ride. (It was a little like surgery that way.) One at a time, each of us thrill-seekers was buckled into a vaguely diaper-like nylon brace, hooked in front to a large rope and then in back to an unfurled parachute. The boat sped up, the chute began to pull upward, the boating guys paid out the rope, one rose into the sky, and the water and the drone of the boat steadily receded. As the boat zipped back and forth across the harbor, far below, one floated in a fairly grand silence thousands of feet above New York. As you can see in the photo, I was as high as the top of the World Trade Center towers. It was pretty awesome.

After a while one was cranked back down and in. I think the only moment when any athletic skill was at all relevant came in setting foot again on the boat. But maybe not even then. Once all three parasail ticket holders had taken a turn, we headed back to the Winter Garden. Everyone seemed to have enjoyed themselves—even the operators seemed a little jolly—but just as we touched the dock, the little girl on board abruptly vomited. She hadn’t succeeded in keeping her fear for her father to herself after all.

What novelists do

Diderot defends what novelists do, in his essay "In Praise of Richardson":

You accuse Richardson of boring passages! You must have forgotten how much it costs in efforts, attentions, moves to make the smallest undertaking succeed, to end a lawsuit, to conclude a marriage, to bring off a reconciliation. Think what you like of these details; but I'm going to find them interesting if they're true, if they bring out passions, if they show people's characters.

They're commonplace, you say; they're what one sees every day! You're mistaken; they're what takes place in front of your eyes every day that you never see. Be careful; you're putting the greatest poets in the dock, under Richardson's name. A hundred times you've seen the sun set and the stars rise; you've heard the countryside echo with song breaking forth from birds; but who among you has felt that it was the noise of the day that rendered the silence of the night so touching? All right, well, there are moral phenomena that exist for you the same way physical phenomena do: outbreaks of the passions have often reached your ears; but you are very far from knowing all that there is in the way of secrets in their tones and in their expressions. There's not a single one that doesn't have its own physiognomy; all these physiognomies appear in succession on a face, without its ceasing to be the same; and the art of the great poet and of the great painter is to show you a fugitive circumstance that had escaped your notice.

Debtmageddon vs. the robot utopia

It seems likely to me that almost everything prescribed by politicians as a remedy for America’s economic doldrums is wrong. I’m not an economist, so my opinion should probably be taken with a grain of salt. But since reading the news has begun to take on an Alice in Wonderland quality for me, I wanted to try to set down in words how my understanding diverges from theirs.

Just so you know where this is headed: I suspect that the flow of money in America has broken down because wealth is too highly concentrated, and that for at least a generation or so, the government ought to tax the rich heavily and spend on the poor and middle class just as heavily.

Why do all politicians and most pundits recommend the opposite? Flawed metaphors, I think. Most people make a natural comparison between a nation’s budget and a family’s. If a family is sliding into debt, the only remedies are to earn more and spend less. But a nation’s economy is not at all like a family’s. For one thing, within most families, communism prevails: the rule governing money is, From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs. For better or worse, this doesn’t happen to be the rule governing money in America at large. Also, within most families, money is not exchanged for labor. In a pedagogical, largely symbolic way, Jimmy may be given $2 a week in exchange for taking out the garbage. But the person who cooks and cleans does not clock his hours; the children do not buy their dinners. The exchange of labor and goods within a family is for the most part unmeasured and invisible, and it makes more sense to understand a family as a group of people functioning a single economic agent. If the sort of thing that brings a family from debt to prosperity also helps a nation, it’s logical coincidence. Family and nation are so unlike each other that there’s no reason to expect it to.

The nation-family metaphor is nonetheless powerful. Even though most economists believe that reduced government spending will worsen the current recession, almost all politicians have caved into the “common-sense” idea that a nation in economic trouble ought to reduce its debt, leaving Paul Krugman to cry in the wilderness. The metaphor also drives, I suspect, another popular economic idea with almost no empirical support, namely, the notion that instead of taxing the wealthy, the government should reward them, in hopes that the wealth they accumulate will trickle down to others in the nation. The wealthy have proven that they know how to make a profit, this line of reasoning goes; get out of their way and let them make the economy grow.

The notion appeals, I suspect, because it, too, would make sense if a nation were like a family. In fact it’s excellent economic advice for a family. If Mother is a whizbang software engineer and Father’s just a freelance writer, it doesn’t make economic sense to tax them with household chores equally. Father should change more diapers and wash more dishes, freeing up Mother to devote more energy on coding the latest breakthrough app. (Whether this sort of inequity is good for the marriage bed, as well as for the pocketbook, is a different question. But it’s well understood that marriages are economically more than the sum of their parts only when spouses differentiate in their skills and tasks, rather than splitting all responsibilities identically.) If the richest people in a nation were analogous to the primary breadwinners in a family, and if income taxes were analogous to housekeeping chores, then it would make sense for the nation as a whole to indulge the rich in their profit-making and to believe in the existence of the trickle-down fairy. But neither analogy holds. Mother the software engineer, remember, deposits her paycheck every week in the family’s communal bank account; this bank account feeds her freeloading children, not to mention the dog; Mother may even let Father the freelance writer buy a new laptop that his personal earnings don’t yet justify. By contrast, when a corporate executive is given a break on his capital earnings tax, he is thereby exempted from, say, providing food for fellow Americans who can’t earn enough to feed themselves or investing in the future earning potential of a worker who’s not yet up to speed. Yes, he’s now able to make money faster, but the reason that other family members make sacrifices for Mother the software engineer is that they know she’s going to share her wealth—that her wealth is also theirs. The wealth of the little-taxed corporate executive is only his.

Proponents of trickle-downism will argue that the little-taxed corporate executive will in fact share his wealth by spending it, and that his purchase of goods and services will drive economic growth more efficaciously than mere giveaways would. But it turns out that the executive doesn’t spend more, or not enough more for his increased spending to be helpful to the economy—for the simple reason that he doesn’t need to. In the hands of rich people, money moves slowly. That’s what it means to be rich: you have more money than the cost of all the things you need or want. A poor person, by contrast, needs more than he can afford. The poor therefore spend money faster. If you want to boost a nation’s economic growth, it’s better to give to the poor, not the rich. A dollar given to a poor man multiplies faster, Keynes observed, than a dollar given to a rich man.

Economic inequity has been extremely high in the past decade, much as it was in the 1920s and 1930s. The popular understanding of the Great Depression is that it ended because World War II finally obliged American politicians to forget their prudence, and borrow and spend enormous sums. Supposedly this great deficit expenditure stimulated the American economy, like an adrenaline shot. Maybe. But what if the metaphor of stimulation is wrong too? What if it wasn’t the deficit spending of World War II that stimulated the American economy, but the war’s redistribution of wealth? The war obliged America to employ a literal army of people as soldiers and factory workers, and after the war, America felt obliged to continue to reward the working classes with expanded social services, including free higher education for veterans. The period from World War II to the 1970s turned out to be the greatest era of prosperity America has ever known. Is it a coincidence that it followed a massive, government-run redistribution of wealth, which happened to take the form of a war? When TARP and a fiscal stimulus bill were passed a couple of years ago, I remember thinking to myself, well, if the mainstream economists are right, and the problem with America can be remedied by an injection of deficit spending, then my gloom will be disproved. But if my suspicion is right that the underlying problem is economic inequity, then no stimulating injection, however large, will succeed. The economy will be lackluster until something happens that shifts wealth from the rich to the poor. Such a shift is unlikely in today’s political climate, of course. Political power naturally follows wealth, so the rich, owning as they do a disproportionate share of the nation’s wealth, now also control a disproportionate share of its political decisions. In a catch-22, the inequity undermining the economy makes impossible the political action needed to remedy it.

Why haven’t our current wars had the same effect that World War II did? I don’t know. Maybe we’re not paying our soldiers enough; maybe the military’s heavy investment in technology and equipment has muted war’s impact as a redistributor of wealth. (And maybe, of course, I’m wrong. I don’t have the statistical chops to back up this analysis.)

The mention of military technology brings me to my last idea. This is the challenge of the robot utopia. You remember the robot utopia. You imagined it when you were in fifth grade, and your juvenile mind first seized with rapture upon the idea of intelligent machines that would perform dull, repetitive tasks yet demand nothing for themselves. In the future, you foresaw, robots would do more and more, and humans less and less. There would be no need for humans to endanger themselves in coal mines or bore themselves on assembly lines. A few people would always be needed to repair and build the robots, and this drudgery of robot supervision would have to be rewarded somehow, but someday robots would surely make wealth so abundant that most people wouldn’t need to work and would be free merely to enjoy and cultivate themselves—by, say, hunting in the morning, fishing in the afternoon, and doing literary criticism after dinner.

Your fifth-grade self was wrong, of course. Robots aren’t altruistic beings; they’re capital investments; and though robots may not ask to be paid, their owners demand a return on their investment. We now live in the robot utopia, which isn’t one. Thanks in large part to computerized mechanization, manufacturing productivity in the past century has increased many times over. Standards of living are higher than they ever were, but we no longer need as many humans to work as we once did. Perhaps not coincidentally, human wages, in America at least, have stagnated since the 1970s. If humans made no more money in the past four decades, where did the wealth created by the higher productivity go? Toward robot wages, as it were. The owners of the robots took the money—that is, the capitalists. Any fifth-grader can see where this leads. At some point society has to choose. Either society accepts the robots’ gift as a general one, and redistributes the wealth that the robots inadvertently concentrate, or society allows the robots to become the exclusive tools of an ever-shrinking elite, increasingly resented, in confused fashion, by the people whom the robots have displaced.

The robots are here. By now they automate even much of our social lives. You might compare the political challenge they represent to what’s known as the “resource curse”—the infamous difficulty that oil-rich nations have in preserving democracy while sharing the oil’s proceeds. Do we want to be Norway or Saudi Arabia? The choice seems to be between democratic socialism and tyranny. I know my understanding will strike many as implausible, if not unspeakable: I’m saying that the country is suffering economically because it doesn’t know what to do with all its surplus wealth.

I review a book without meaning to

I'm tempted to do something I don't usually do: write critically of a book that I have no intention of finishing. The book in question bothered me. I've been tussling with my botheration, trying to figure out what exactly I disliked, and I wonder if it will clarify my objections if I try to put them into words. Since it doesn't seem quite fair to the book to judge it without finishing it, I'm not going to name it or its author. This disguise is not meant to be impenetrable. Please understand the anonymity as a polite veil, not at all hard for an internet user of average resourcefulness to tear away.

As a reviewer, I'm sent a fair number of books by publishers, and I don't remember whether I happen to have requested this one, though I suspect I didn't. It arrived while I was suffering from a mild fever, a condition that's relevant because I won't be able to get to the bottom of my final dislike of the book unless I start with its initial appeal, which was considerable. I was feeling muzzy, bored, and a little vulnerable. My attention had been tenderized by a sick-day's indulgence in Twitter. The book in question is a novel, written in the first person. In the first few pages, in simple and declarative sentences, modestly spiced with British slang, the heroine-narrator lets herself be seduced into a risky sexual encounter. She enjoys herself intensely—the experience seems to fracture an idea of herself that she has—but she doesn't seem to have done this kind of thing before, and it isn't at all clear that she's going to be all right.

I kept reading, conscious that the plain grammar (subject-verb-object) and the explicit sex suited the debilitated state of my mind. The sentences practically read themselves. Sometimes, as a writer, one is aware that one also has the specious motive of doing something so as to be able to write about it later, and my conscious rationalization for continuing the novel included the somewhat recursive notion that if I did continue to read, I might be able to mine the experience for an essay about the kind of book that appealed to people who were spending too much time on Twitter and whose brains were befogged by toxins, viral or otherwise—about the limitations that the novel as a genre might have to accept in order to seize and hold attention in the current environment.

Less consciously, I had perhaps identified with the heroine, as someone who, like myself in an earlier era of my life, was putting herself in danger through a sexual responsiveness that she didn't understand.

My resistance to the text first became conscious to me in questions of style. Though technically written in the past tense, the short, plain sentences and their narrow time-focus gave the impression of a story unrolling in the present tense only. The heroine never thought about her past, though visits with a grandmother and with parents suggested that she did have one. She never reflected on how she had come to have the career that she did, or what had drawn her to her best friend, let alone on how she had become so cut off from her inner life that she could only return to it through episodes of violent, near-anonymous sex. This limitation in the telling of the story seemed one, however, with the urgency of the story's appeal. The narrator was Everywoman; the reader was not put at a distance by any details of her past or by any elements of her personality that the reader might not happen to share. On the contrary, the reader was constantly being invited to join in a fantasy: What if I were to have an irresponsible fling? What if I were to antagonize my friends? What if I were to mess up my safe but boring job? There was no awareness of anything in the heroine's life or mind that might hold her back. She was completely free. Or, to look at another way, her vanity and neediness were uncompromised by any consideration of other people as beings just as real as she was. The book began to remind me of Jay McInerny's Bright Lights, Big City, which I read twenty years ago when I was under the impression that I ought to keep up with best-sellers; the transgression began to seem monotonous in a similar way.

Because of the narrow focus—limited to the narrative's present, and to the perceptions of a narrator not motivated to understand anyone around her—a number of scenes had the flat feeling-tone of a certain kind of comedy routine, which depends for its success on the audience's collusion in a sadistic ridicule or dismissal of embarrassing feelings. Some of these scenes "worked" as jokes, but on second thought, seemed unlikely to be able to "work" in the real world. In one such scene, the heroine half-jestingly hits some children that she has been asked to take care of, and the children respond by precociously and coldly turning against her and voicing their hatred of her. I found myself thinking, well, in fact it is kind of awful of the heroine to have hit the children, but I doubt that real children would be able to find on such short notice sufficient insight and sufficient confidence to punish a faulty caregiver. In another scene, the heroine undresses while drunk for a man who is disgusted by her drunkenness, and I found myself thinking that if this character was charming enough to hold my interest as a reader, she probably wouldn't be the sort who, even drunk, would so badly misjudge the responsiveness of a potential suitor. In real life, she would have noticed his recoil, even through the haze of alcohol, before going quite so far.

I stopped reading when I found myself resorting to diagnosis of the characters. The heroine becomes obsessed with the man she has the sexual encounter with, despite his commandeering, abusive manner, or maybe because of it. He is portrayed as someone at ease with himself—at ease with his sadism and manipulation. Oh, I thought, a sociopath, charming and dangerous. And the heroine's focus on connection with him as the only source of meaning in her life: Oh, I thought, she's a borderline personality, who disintegrates unless she maintains contact yet needs the drama of always falling out of contact. It occurred to me that in real life the story of these two people would be so exhausting to hear about that it would be hard to stay focused, while listening, on how sad it was. In real life, it would end badly, unless disrupted by care and insight. It would probably end badly even if it were disrupted by care and insight. One way for it to end would be by his killing her. I thought of a book with a similar setup (whose plot and ending I will implicitly be giving away, in order to make my analogy, so look away if you need to), Muriel Spark's The Driver's Seat, though Spark's heroine understands herself in a way that this novel's heroine does not seem to. Though I admire Spark and would be happy to re-read her Girls of Slender Means or Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, I didn't enjoy The Driver's Seat and have no intention of ever re-reading it. Once I made the comparison, I couldn't bear to keep reading the novel at hand—the thought of having to sit through the tedium of a borderline's relationship with a sociopath, only to be punished for my patience with an unhappy ending, was too much.

Does he kill her? I flipped to the end. (Spoiler ahead, obviously; if you think you might track down this book and read it despite me, stop reading now.) It turns out that the author—in a reversal of expectations that to my eye again functions better as a joke than as a plausible rendering of human experience—gives her heroine the opportunity and the strength of purpose to kill her beloved torturer. I don't think this is really a happier ending than it would be if he killed her; it certainly wasn't an ending that I wanted to spend any amount of time or effort reaching, once I knew it. What keeps Spark's Driver's Seat interesting (though it remains unpleasant) is that the borderline personality in that novel fails to find the sociopath she's looking for and has to make do with another personality type altogether, by blackmailing him. There's no such complexity of motive and outcome in the new novel. I don't think the unexpected reversal would have any chance of convincing a reader if it weren't for the stylistic constraints on its telling, which make it harder to see how unlikely it is—if it weren't for the impairments that also function as appetite stimulants.

Admittedly, I broke the rules of the reader-writer contract. It's possible that if I read every word of the novel in sequence, I would find the reversal of roles at the end psychologically plausible. I doubt it, though. I suspect that if such "funny," impoverished consciousness—the final triumph of "showing" over "telling," in the specious language of writing instruction—is the only way to hold attention in a splintered world, the novel is in trouble. If the novel must always be recapturing the reader's attention, by prurient means, the novel is in the plight of a needy borderline, doomed to tedious pursuit of the cruel, elusive reader, who alternates between taking his pleasure from the book and dropping it for more compelling pleasures elsewhere. My own reading pattern here—beginning to read almost in scorn for the book, finding itches scratched by it almost despite myself, ultimately dismissing and abandoning the book—is weirdly complicit. I've even kept my encounter with the book, like the heroine's with her sociopath lover, anonymous, as if my meeting with this book were somehow disreputable for both of us. I must have fallen more under its spell than I realized. For the sake of disenchantment, then, maybe I should reveal the name of the book after all: True Things About Me, by Deborah Kay Davies. It comes out next week in paperback from Faber & Faber.