More than a decade ago, I did a little bit of fear arbitrage. I was facing a very minor bit of surgery, so minor that after the fact it turned out that it hadn’t been necessary at all, though of course I didn’t know that at the time. I had decided that I was going to stay conscious during it, on the general principle that it isn’t a bad idea to keep an eye on a person cutting into you with a knife. Indeed, when the fateful day arrived, I was able to watch the doctor making her incisions, and my curiosity turned out to be more powerful than my squeamishness. (I remembered being especially fascinated by the glistening white layer of fat that lay just beneath my skin, deeper than even the worst scraping of a knee had hitherto revealed. At least I think it was fat.) I knew in advance that thanks to local anesthetics I wasn’t going to feel any pain, but to say that I dreaded the surgery would be an understatement. I hate to go the doctor even for check-ups.

More than a decade ago, I did a little bit of fear arbitrage. I was facing a very minor bit of surgery, so minor that after the fact it turned out that it hadn’t been necessary at all, though of course I didn’t know that at the time. I had decided that I was going to stay conscious during it, on the general principle that it isn’t a bad idea to keep an eye on a person cutting into you with a knife. Indeed, when the fateful day arrived, I was able to watch the doctor making her incisions, and my curiosity turned out to be more powerful than my squeamishness. (I remembered being especially fascinated by the glistening white layer of fat that lay just beneath my skin, deeper than even the worst scraping of a knee had hitherto revealed. At least I think it was fat.) I knew in advance that thanks to local anesthetics I wasn’t going to feel any pain, but to say that I dreaded the surgery would be an understatement. I hate to go the doctor even for check-ups.

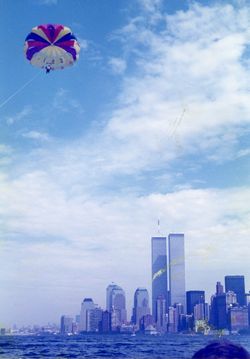

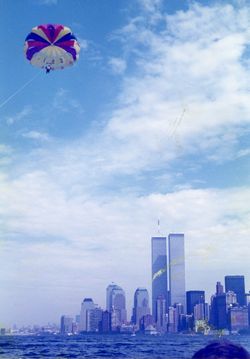

Mulling over my fate, I berated myself over my cowardice for days until, in defense against my self-attacks, I started listing things that other people were afraid of that for me held no terrors at all. I had recently seen ads—I no longer remember where, maybe in one of the weekly giveaway newspapers that I used to read at lunch in the local slice joint—for parasailing in New York Harbor. I probably will never have the courage to jump out of a plane, but parasailing didn’t frighten me. By lifting you up into the sky, a parachute-sail proves its ability to keep you up there, or so my mind, surprisingly rational on this point, concluded. If modern medicine had sentenced me to be more brave than I wanted to be about surgery, it only seemed fair for me to reward myself by enjoying a risk that didn’t scare me.

I called an old friend who had survived lung cancer in childhood and had recently started taking multi-day, high-endurance hikes in the West; he was game, too. Across the street from the then-extant World Trade Center, just outside the Winter Garden, where a long quote from Frank O’Hara is carved in marble, we met the two men running the parasailing outfit. They were working-class New Jersey boating guys, a little brusque. I think we paid them cash, but I don’t remember how much—maybe $100 apiece? I remember that it was a lot for a graduate student, but not a lot compared to other New York luxuries. The operators didn’t make any small talk, nor did they offer any marketingesque pleasantries about the adventure we had chosen and how meaningful it might or might not be. They merely nodded to the life jackets, unmoored the boat, and motored out into the harbor with us. In the face of their alpha-male taciturnity, I remember scrutinizing the winch at the back of the vessel for clues about how the whole thing was going to work. For further clues there were only the occasional radio exchanges between our boat and the harbor police, terse and somewhat cryptic, from which I gathered that parasail operators were more tolerated than welcomed by the water authorities, who expected us to wait patiently until more-functional marine traffic had passed. The operators may also have had to clear things with air traffic control, or at least with the nearby helipads—I can’t recall. My friend and I weren’t the only passengers; there was also a man in his early thirties, who seemed to be a financial services type. His wife and elementary-school-age daughter were keeping him company but weren’t going to go up themselves.

It soon became clear that the boating guys hadn’t bothered to explain the parasail procedure to us because there was little for a passenger to do except enjoy the ride. (It was a little like surgery that way.) One at a time, each of us thrill-seekers was buckled into a vaguely diaper-like nylon brace, hooked in front to a large rope and then in back to an unfurled parachute. The boat sped up, the chute began to pull upward, the boating guys paid out the rope, one rose into the sky, and the water and the drone of the boat steadily receded. As the boat zipped back and forth across the harbor, far below, one floated in a fairly grand silence thousands of feet above New York. As you can see in the photo, I was as high as the top of the World Trade Center towers. It was pretty awesome.

After a while one was cranked back down and in. I think the only moment when any athletic skill was at all relevant came in setting foot again on the boat. But maybe not even then. Once all three parasail ticket holders had taken a turn, we headed back to the Winter Garden. Everyone seemed to have enjoyed themselves—even the operators seemed a little jolly—but just as we touched the dock, the little girl on board abruptly vomited. She hadn’t succeeded in keeping her fear for her father to herself after all.