Harvard University Press has just put out Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History by Devin McKinney, who writes as if he were very well caffeinated. I don’t really have time to read the book right now, but I’ve been glancing at it, and the other day I saw that he goes into the “Paul is dead” myth-slash-marketing campaign, which I remember first learning about at age twelve, from a friend a few years older, who disapproved of it as a distraction from the music.

This is a roundabout way of introducing my anecdote. McKinney’s not-quite-academic treatment reminds me of a full-on-academic treatment that I came across in grad school and which utterly flummoxed me. I’ve never got to the bottom of it. It’s in a very Foucauldian essay, “The End of Autobiography,” by Michael Sprinker, in editor James Olney’s Autobiography: Essays Theoretical and Critical (Princeton University Press, 1980), p. 322:

This passage [a quote from Gravity’s Rainbow] presents an instance of a pervasive and unsettling feature in modern culture, the gradual metamorphosis of an individual with a distinct, personal identity into a sign, a cipher, an image no longer clearly and positively identifiable as “this one person.” A few years ago, American popular culture underwent a minor crisis when it was learned that Paul McCartney of the Beatles had died a few years previously and had been replaced in the singing group by the winner of a Paul McCartney look-alike contest. The scandal died quietly after a few months, probably because “Paul McCartney” had long since ceased to have any significance as an individual and had become, as far as anyone besides his wife and children was concerned, simply a face and a voice. As long as the face and the voice remained essentially the same, it mattered little whether this was the real Paul McCartney or some impostor. In fact, the idea of an impostor had little relevance to the case, since all that mattered was the music that the Beatles produced, and no one was willing to argue that it had diminished in quality since McCartney’s alleged demise.

The same problem crops up when one attempts to talk about “the author of Gravity’s Rainbow….

As an impressionable young grad student, my first impulse, naturally, was to believe what was in the assigned reading and wonder if Paul really was dead, and my neighbor, all those many years ago, had been wrong about it being a hoax. But then I thought, No, no, no, this is the sort of thing you would have heard about. But evidently it’s not the sort of thing that Michael Sprinker had heard about, or his editor, or his publisher. Then I thought, Am I missing a joke here? Is this some postmodern stunt, where the critic is pretending to have fallen for a hoax, in order to enact the hoaxability of the reader? But the prose is pretty darn po-faced, and I had to wonder: Could the academic world really affect such a lordly indifference to the mere facts about the Beatles as to commit such a howler?

Another possibility: Maybe when Sprinker wrote the passage, he was himself a graduate student, peering over the brink of academia’s norms, and he threw the paragraph in, just to see whether there would be any splash, the way that Mark Twain once, in a mild descriptive passage, threw in a mention of “blue sky, interrupted by flocks of low-flying esophagi” (I quote from memory, and I’m sure innacurately), just to see if anyone actually ever read the mild descriptive passages in magazine fiction.

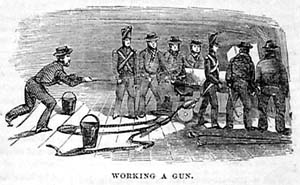

The age-of-sail nerd in me loves the detail in Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. And surely I’m not the only such nerd grateful to hear eight bells rung, to observe a beating to quarters, to see the decks being holystoned, and to appreciate that the left side of the ship in 1805 would have been called “larboard,” not “port,” because Captain FitzRoy (Charles Darwin’s half-mad companion on the HMS Beagle) hadn’t yet suggested renaming it so that it didn’t rhyme with “starboard.”

The age-of-sail nerd in me loves the detail in Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. And surely I’m not the only such nerd grateful to hear eight bells rung, to observe a beating to quarters, to see the decks being holystoned, and to appreciate that the left side of the ship in 1805 would have been called “larboard,” not “port,” because Captain FitzRoy (Charles Darwin’s half-mad companion on the HMS Beagle) hadn’t yet suggested renaming it so that it didn’t rhyme with “starboard.”