I had occasion to observe, over the weekend, that I was once blond. But I sensed that I was listened to with polite disbelief. Here, then, is some evidence. The photograph is from circa 1975, when I lived in Orange County, California, which was not then called by its initials, to my knowledge.

Author: Caleb Crain

Notebook: “There She Blew”

“There She Blew,” my review of Eric Jay Dolin’s Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America, is in the 23 July 2007 issue of The New Yorker. Herewith a few web extras and informal footnotes.

As ever, my first thanks go to the book under review. I also consulted the conservationist and historian Richard Ellis’s Men and Whales (Knopf, 1991), which takes the story of whaling beyond America, and the economists Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter’s In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 (University of Chicago, 1997), which contains empirical data and insights that will interest Ph.D.’s as well as M.B.A.’s. The best documentation of Melville’s life as a whaler is in Herman Melville’s Whaling Years (Vanderbilt, 2004), a 1952 dissertation revised by its author, Wilson Heflin, until his death in 1985, and astutely edited for publication by Mary K. Bercaw Edwards and Thomas Farel Heffernan. (It’s from a note in Heflin’s book that I found the description of sperm-squeezing in William M. Davis’s 1874 memoir.) Two nineteenth-century memoirs of whaling that I refer to—J. Ross Browne’s Etchings of a Whaling Cruise and Francis Allyn Olmsted’s Incidents of a Whaling Voyage—are available online thanks to Tom Tyler of Denver, Colorado, as part of his edition of journals kept aboard the Nantucket whaler Plough Boy between 1827 and 1834. William Scoresby Jr.’s Account of the Arctic Regions, with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery is available in Google Books. (For the record, though, I read on paper, not online. I’m not really capable of reading books online.)

Also very useful was Briton Cooper Busch’s “Whaling Will Never Do for Me”: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1994), which told me about bored shipboard wives and the whaler who read Moby-Dick while at sea, and Pamela A. Miller’s And the Whale Is Ours: Creative Writing of American Whalemen (Godine, 1971), my source for the quatrain about sperm whales vanishing from “Japan Ground.”

Now for the wildly miscellaneous. While I was researching the review, some Eskimos killed a bowhead whale off the shores of Alaska and found in its blubber the unexploded explosive tip of a bomb lance manufactured in the 1880s; the discovery got a short paragraph in the New York Times (“This Whale’s Life . . . It Was a Long One”), and a longer explanation on the website of the New Bedford Whaling Museum (“125-year-old New Bedford Bomb Fragment Found Embedded in Alaskan Bowhead Whale”). The NBWM has some great photographs of whaling in its online archives, from an inadvertently campy tableau of a librarian showing a young sailor how to handle his harpoon in the 1950s (item 2000.100.1449), to a sublime and otherworldly image of a backlit “blanket piece” of blubber being hauled on board a whaler in 1904 (item 1974.3.1.93). The blanket piece was photographed by the whaling artist Clifford W. Ashley, as part of his research for his paintings; he also took pictures of a lookout high in a mast (item 1974.3.1.221), a sperm whale lying fin out beside a whaler (item 1974.3.1.73), the “cutting in” of a whale beside a ship (item 1974.3.1.34), and whalers giving each other haircuts (item 1974.3.1.29). Though taken in 1904, they’re the best photos of nineteenth-century-style whaling I’ve seen, and they’re also available in a book, Elton W. Hall’s Sperm Whaling from New Bedford, through the museum’s store.

The best moving images of whaling are in Elmer Clifton’s 1922 silent movie “Down to the Sea in Ships,” which features Clara Bow as a stowaway in drag and has an absurd plot, complete with a villain who is secretly Asian. It stars Marguerite Courtot and Raymond McKee (who was said to have thrown the harpoon himself during the filming), as well as real New Bedfordites and their ships, as Dolin explains, and even has a scene of Quakers sitting wordlessly in meeting, the purity of which tickled me. It has been released by Kino Video on DVD and is available via Netflix as part of a double feature with Parisian Love. The NBWM has a great many stills; try searching for “Clifton” as a keyword.

If photographs strike you as too anachronistic, you can find the occasional watercolor whaling scene in the nineteenth-century logbooks digitized by the G. W. Blunt White Library of the Mystic Seaport Museum, such as these images from the 1841-42 logbook of the Charles W. Morgan (MVHS Log 52, pages 37 and 43). There is more scrimshaw than you will know what to do with at the Nantucket Historical Association. If you want to hear whales, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has at least two websites with samples, and there are more here, courtesy of the University of Rhode Island.

The conceptual, book-based artist Alex Itin has an intriguing video collage of Moby-Dick the text and Orson Welles the actor; Welles tried a number of times to stage a version of the novel. And much further down the brow of culture, the Disney corporation did an animated book review of Moby-Dick a few years ago. (I can’t promise it won’t work your last nerve.) Last but not least, here are NOAA’s estimates of current whale populations, by species, and the homepage of the International Whaling Commission, responsible for the animals’ welfare.

Photo credit: Harry V. Givens, photographer, “Whale Skeleton, Point Lobos, California,” American Environmental Photographs Collection (1891-1936), AEP-CAS206, Department of Special Collections, University of Chicago Library (accessed through the Library of Congress’s American Memory website).

Busy month, largely offline

My boyfriend, Peter Terzian, has just published three great pieces. One is available online, a deft review in Newsday of Jenny Uglow’s biography of Thomas Bewick, the engraver of rural scenes who was a contemporary of Wordsworth. When you next visit a newsstand, you should also pick up the July/August issue of Columbia Journalism Review for his interview with environmental historian Rebecca Solnit, and the July/August issue of Modern Painters for his review of Novels in Three Lines, the microfiction romans durs of Félix Fénéon.

Notebook: Aimee Semple McPherson

“The Miracle Woman,” my review of Matthew Avery Sutton’s biography Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America appears in the 19 July 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books. (It’s not available for free online. Please subscribe! Otherwise someday there will be no more steamboats…) What follows is supplemental, and not likely to make sense until you read the article.

As ever, my first thanks are owed to the book under review. A couple of other sources made it into the article’s footnotes: Edith L. Blumhofer’s Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody’s Sister (Eerdmans, 1993) and Daniel Mark Epstein’s Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson (Harcourt, 1993). Since I didn’t have room in my article to give much sense of these books as books, it may be worth saying here that their styles are quite different: prose-poetical and trusting in Epstein’s case, authoritative and reserved in Blumhofer’s. Sutton praises both of them in his book, and writes that he hurried past McPherson’s youth because they covered it so well, choosing instead to focus on her later years, which they scanted. That’s true of Blumhofer, whose tact constrains her to a cryptic brevity when she reaches the bickering and scandal of McPherson’s last decade. Epstein, though, provides a few more of the late twists and turns than Sutton does, and may in the end give the most complete picture. (Unfortunately, he’s not always perfectly accurate. For example, he writes that McPherson failed to attend her father’s funeral in 1927, but he is contradicted by the obituary he quotes, which states that her father died at eighty-five, his age in 1921. Indeed, Blumhofer reports that McPherson’s father died in 1921, and has evidence, furthermore, that Aimee did return to her hometown for the service.) The other important biography of McPherson is Lately Thomas’s Storming Heaven: The Lives and Turmoils of Minnie Kennedy and Aimee Semple McPherson (Morrow, 1970), which traces McPherson’s path through the pages of American newspapers in great detail; on the subject of McPherson, Thomas notes, the “press record is almost inexhaustible.” The result is somewhat unfiltered and “bitty,” as the English say, but the newspaper photographs that illustrate the book alone make it worthwhile.

In 1999, a University of Virginia undergraduate named Anna Robertson put together a slide show of McPherson photographs, an Aimee Semple McPherson cut-out doll published by Vanity Fair in the 1920s, and a number of other images and documents. There are also pictures on the website for “Sister Aimee,” a PBS documentary that drew on Sutton’s book, and on a webpage about McPherson managed by the Foursqure Church, the Pentecostal denomination she founded.

In his novel Elmer Gantry, Sinclair Lewis modeled the character of Sharon Falconer on McPherson. He described Falconer’s voice as “warm, a little husky, desperately alive,” and that matches McPherson’s, which you can hear preaching about Prohibition at the History Matters website. You can also hear early recordings of McPherson in a 1999 radio program, “Aimee Semple McPherson — An Oral Mystery,” part of NPR’s Lost and Found Sound series.

An odd side note, which I never even tried to sandwich into my article: Blumhofer writes that after Aimee and her second husband, Harold, separated in 1918, Harold preached for a while with “John and Elizabeth Ashcroft, evangelists in Maryland, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania.” From scanning a few online biographies and genealogies, I’m fairly sure that these were the grandparents of former attorney general John Ashcroft.

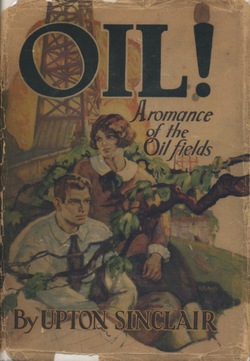

Oh, and the photo above. Aimee Semple McPherson appears as a character in Upton Sinclair’s 1926 novel Oil!, but Sinclair switched McPherson’s sex when he novelized her. Like McPherson, Eli Watkins is a preacher in the Pentecostalist tradition who vanishes and is thought to have drowned; he comes back with a tale of having been held up in the water by three angels, though the rumor is that he spent the missing days in a beachfront hotel with an attractive young woman. That isn’t Eli Watkins on the book’s cover, which is the Grosset & Dunllap edition, because Watkins’s story is really no more than a minor subplot. The novel mostly concerns an idealistic young man, Bunny Ross, who discovers as he grows up that the oil business, which his father works in, corrupts politicians and civic life generally. Eventually Bunny becomes a “millionaire red,” vowing to spend his inheritance on a socialist labor college. When Bunny hears Eli preaching on the radio what he knows to be lies, he thinks to himself,

The radio is a one-sided institution; you can listen, but you cannot answer back. In that lies its enormouss usefulness to the capitalist system. The householder sits at home and takes what is handed to him, like an infant being fed through a tube. It is a basis upon which to build the greatest slave empire in history.

The woman in the illustration may be Eli’s sister, Ruth, a sort of shy shepherdess, who never quite turns into the love interest.

Pakistan diary

My friend Elise Harris recently returned from three months in Lahore, Pakistan. She recorded her trip in a travel diary, full of telling and moving human details, and it has just been published by the online, Brooklyn-based literary magazine Harp & Altar.

At 5:45pm, Ahmad and I go out for smoothies. . . . A local high school girl comes up to us. She says that she is doing a photo essay for a school competition. The subject is “cultural deviancy.” May she take our photo?

She does. It’s an embarrassing moment. Ahmad says, “I think it’s true, we are deviating from our culture. But I think values are the more important thing. You can change culture but keep the same values.”

Elise is stalked by a clumsy intelligence agent; accepts a motorcycle ride from a complete stranger to attend a ceremonial confrontation on the India-Pakistan border; and talks long into the night with new friends about romance and sexuality, and faith and skepticism. The diary becomes a kind of meditation, too, on the mix of revelation and disguise that go into reporting. (Since it’s a long piece, and the type on the Harp & Altar website is small, I recommend cutting-and-pasting the whole thing into a Word document in a large and legible font and printing it out.) Highly recommended.