Toward the end of Midnight Oil, V. S. Pritchett’s 1971 memoir of his apprentice years as a writer, he recalls how he and his second wife settled down in the English countryside in 1938, in anticipation of World War II. “I got out my bicycle,” he writes, “for we did not own a car, and pedalled over Berkshire until I found an empty, isolated, farmhouse in the Lambourn valley, eight miles from Newbury-horse-racing country.” In Pritchett’s description, the place sounds idyllic, and moreover it was a site that another work of literature had already made famous. “I paid £1 a week,” Pritchett writes,

for a sedate, solid, ivy-covered Georgian house of the spacious farming kind, a place with a large walled garden and apple orchard. The garden ran down to the spring-fed Lambourn river which flooded when the white water buttercups came out. This pleasant place was called Maidencourt—a mis-spelling of Midden-court, I suppose. It lay down a blind lane ending at the railway crossing of the little Lambourn branch line; and then continued as a footpath across the Downs behind us to the Roman Ridgeway above Wantage. From the top there, on a clear day, we could see the spires of Oxford. My wife and I often cycled to Oxford—a good fifty miles there and back—during the war when clothes were scarce, in search of things for our children. I mention this footpath, for it can easily be identified in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, his topography is always minutely exact and is part of his concern with human circumstance.

The footpath in question is indeed memorable to readers of Jude the Obscure. In that novel, the hero Jude Fawley is obsessed at an early age with Oxford, which is given the name Christminster. Shortly after a farmer scolds Jude for having encouraged the rooks that he was hired to scare away, Jude’s great-aunt regrets that his schoolteacher didn’t take Jude with him to Christminster when he left to study there. “Where is this beautiful city, aunt—this place where Mr. Phillotson is gone to?” Jude asks. “Lord!” the aunt replies, “you ought to know where the city of Christminster is. Near a score of miles from here.” A bit later, Jude asks a stranger for directions.

The man pointed north-eastward, in the very direction where lay that field in which Jude had so disgraced himself. . . . The farmer had said he was never to be seen in that field again; yet Christminster lay across it, and the path was a public one. So, stealing out of the hamlet he descended into the same hollow which had witnessed his punishment in the morning, never swerving an inch from the path, and climbing up the long and tedious ascent on the other side, till the track joined the highway by a little clump of trees. Here the ploughed land ended, and all before him was bleak open down.

Not a soul was visible on the hedgeless highway, or on either side of it, and the white road seemed to ascend and diminish till it joined the sky. At the very top it was crossed at right angles by a green ‘ridgeway’—the Icknield Street and original Roman road through the district. This ancient track ran east and west for many miles, and down almost to within living memory had been used for driving flocks and herds to fairs and markets. But it was now neglected and overgrown.

Near the intersection of the northerly path with the Roman ridgeway, Jude finds a barn called the Brown House, from which some roofers claim it’s possible to see Christminster. On his first attempt Jude sees nothing, but later he tries again.

Some way within the limits of the stretch of landscape, points of light like the topaz gleamed. The air increased in transparency with the lapse of minutes, till the topaz points showed themselves to be the vanes, windows, wet roof slates, and other shining spots upon the spires, domes, freestone-work, and varied outlines that were faintly revealed. It was Christminster, unquestionably; either directly seen, or miraged in the peculiar atmosphere.

Is it heaven or higher education? By the illusion that either would admit a striver like him, the boy is doomed, and the Pisgah sight is one of the novel’s recurring images.

The terrain of Hardy’s fictional region Wessex is famously modeled on the real geography of southwestern England. For instance, there really is a “ridgeway,” though it’s now thought to pre-date the Roman era by a few thousand years. You can even find a map of the Ridgeway online. In the early twentieth century, Hardy’s fans and scholars correlated many of Hardy’s settings with their real-world counterparts, so that it’s easy today to look up “Christminster” and find out that it’s really Oxford. The original of the Brown House, Victorian Web reports, on information probably deriving from Herman Lea’s Thomas Hardy’s Wessex (1913), was known in its day as the Red House, to be found five miles south of Wantage. It isn’t easy to find any contemporary references to the Brown House or the Red House, however; I can’t figure out where either of them are in Google Maps.

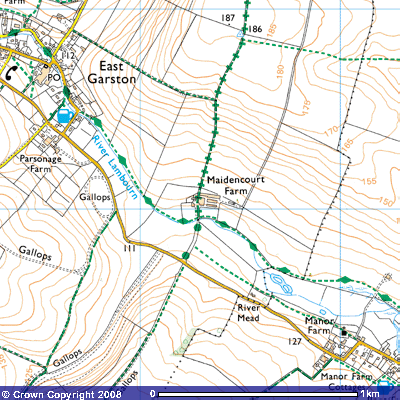

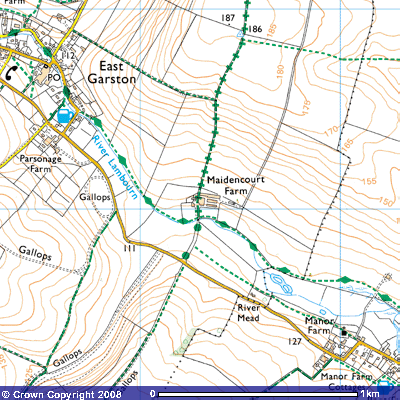

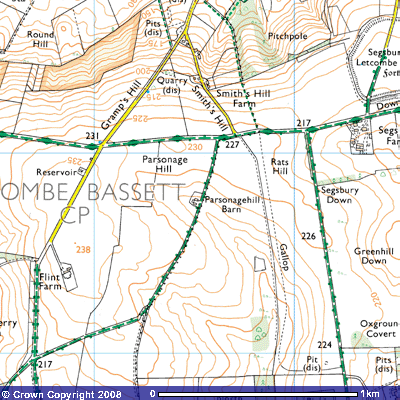

It turns out to be very easy, however, to find Pritchett’s old house, Maidencourt. All you have to do is search Google Maps for “Maidencourt, UK.” For confirmation, here’s a map from the British government’s mapping department, the Ordnance Survey, of the same site.

[Image produced from the Ordnance Survey Get-a-map service.]

There, in light blue, is the River Lambourn, the one that flooded with white water buttercups. It appears that the branch line of the railroad no longer runs close by, but Maidencourt itself is intact, though if you zoom in through Google Maps, you’ll see that it’s not as sedate as it was in Pritchett’s day; it now has an in-ground swimming pool. More important for the literary query here is the track of green plus-signs that runs north from Maidencourt Farm. It isn’t a road, according to the key of the Ordnance Survey’s maps; it’s a “public right of way; a byway open to all traffic.” It is, I strongly suspect, the footpath described by Pritchett as extending “across the Downs behind us to the roman Ridgeway above Wantage”—the one that led to the vantage of Oxford that Pritchett and his wife had shared with Jude Fawley.

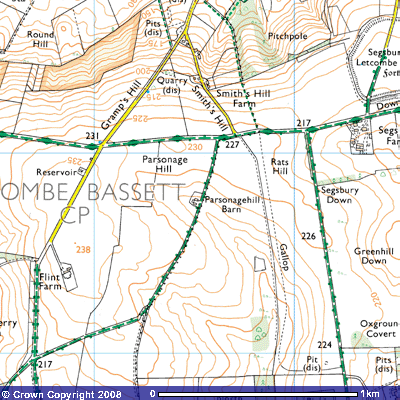

Is it possible to map the route that Jude took? I thought it would be easy, once I found Maidencourt Farm and the Ridgeway. It isn’t, though. The trouble is that the path that Pritchett cycled is no longer a public right of way in its entirety. If you inch your way northward from Maidencourt Farm using the Ordnance Survey’s map, clicking first on Maidencourt Farm itself and then clicking to the north of it, frame by frame, each time advancing a few hundred yards, you soon find that you have to guess where the old path was, because the years have erased large chunks of it. In my first guess, I had the path veering northeast at something called the Furze Border. I thought, reasonably enough, that it ought to have gone through the town of Fawley. Fawley was Jude’s last name, after all, and under the name Marygreen, it was the place where he was raised. (Jude probably joined Pritchett’s path somewhere to the north of where Pritchett began it.) My first guess at the path did cross the Ridgeway eventually. It ran along several major roads in the process, though, and it didn’t cross the Ridgeway at a right angle, as Hardy described. When I looked at my finished result, I noticed the traces of an old path running almost due north from Maidencourt Farm. That path did cross the Ridgeway at a right angle. What’s more, it crossed it at a higher elevation—Flint Farm, just to the southwest of this intersection, stands at 238 meters above sea level. That path became my second, better guess.

[Image produced from the Ordnance Survey Get-a-map service.]

In the map above, the Ridgeway is the green track running east to west, and my second guess for the intersection of Jude’s path and the Ridgeway is at the end of Smith’s Hill Road. (My guess for Jude’s path itself does not appear, of course, because it’s only a guess; it would run roughly parallel to the north-south dotted line labeled “Gallop.”) Flint Farm is to the south and west, but I doubt it’s the prototype for the Brown House; the Parsonage Hill Barn is just as good a candidate. And neither is likely to be right, because Hardy described the Brown House as being more or less on the Ridgeway.

Still, I do have some hope that I’ve got the path right. As confirmation, consider that in the novel, when Jude went to visit his sweetheart Arabella Donn at her home, he first reached the intersection “where the path joined the highway” and then “struck away to the left, descending the steep side of the country to the west of the Brown House. Here at the base of the chalk formation he neared the brook that oozed from it, and followed the stream till he reached her dwelling.” Happily for my speculations, the structure today called Arabella’s Cottage, after the fictional use that Hardy made of it, is to be found to the northwest and downhill from the intersection I’ve identified.

With moderate but not absolute confidence, then, here is my map of Jude’s path, as reconstructed with the help of V. S. Pritchett’s evidence. Walk it at your peril. Unlike Jude and Pritchett, you’ll probably end up trespassing.

View Larger Map